Rural hospitals straining, closing under increasing financial stress

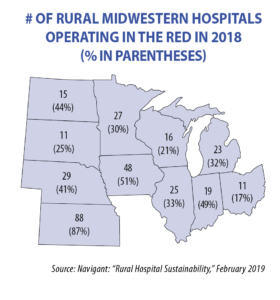

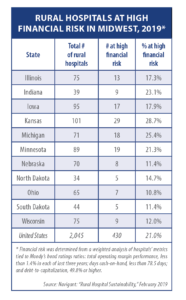

Rural hospitals are a critical component of communities across rural America, but they’re in trouble: 16 in the Midwest have closed since 2010 and a recent study by Navigant suggests 139 more are at financial risk of closure. The National Rural Health Association says that 42 percent of rural hospitals in the Midwest are operating in the red.

While the profitability of urban hospitals has increased over the last five years, that of rural hospitals has decreased. In Kansas, one of 14 states that have not expanded Medicaid, 86 percent aren’t profitable.

Illinois Rep. Tom Demmer, who is director of strategic planning at Katherine Shaw Betha Hospital in Dixon, says the reasons are complex and numerous: Rural residents are on average older and have lower incomes and greater rates of chronic illnesses than urban residents, while higher rates of uninsured, Medicare and Medicaid patients lead to greater levels of uncompensated and undercompensated care.

The 2017 edition of an annual study by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed that from 1999-2014, the age-adjusted death rates for unintentional injuries were approximately 50 percent higher in rural areas than urban areas.

Rural hospitals also lose money on every Medicare, Medicaid, or state insurance plan patient. Rob McLin, CEO of Good Samaritan Hospital in Vincennes, Indiana, says that on a national average, Medicare pays hospitals 88 cents for every dollar spent while Medicaid pays 90 cents.

When a patient comes into a rural hospital with a trauma injury, the hospital generally stabilizes the patient and transfers him or her to a trauma center. The hospital’s portion of the total bill is submitted to the patient’s insurance company and applied to the patient’s deductible. If the patient can’t pay the deductible, the hospital takes the loss, while care at the trauma center is covered by insurance because it is beyond the deductible.

The Affordable Care Act, which encouraged a move away from the traditional fee-for-service model, also is hurting rural hospitals. The ACA also made at least eight Medicare reimbursement cuts; and Congress made an additional 2 percent across-the-board cut on Medicare as part of sequestration in 2011. “All of these things have created a perfect storm for rural, already vulnerable hospitals,” says Alan Morgan, chief executive officer for the National Rural Health Association.

States beginning to respond

Illinois began to address some of these issues in the 2017-18 legislative session with SB 1773 and SB 1469, which redesigned how the state allocates Medicaid funding to hospitals.

“Previously, Illinois hospitals received a fixed amount of money based on data sets as old as 2005,” Demmer says. “Hospital care has dramatically changed, and it was important to make sure that the money followed the patient based on the actual care the hospital provides.”

Illinois hospitals treating a large portion of Medicaid patients now will get additional funding, with changes occurring in three phases over six years so hospitals have time to adjust to the new formula. The bipartisan redesign also resulted in $360 million in new federal funding, including more money for behavioral health, perinatal care and graduate medical education.

The bill also provides $260 million for hospitals to adapt to changes in their community. One hospital converted its beds to a geriatric psychiatry ward, and another transformed a surgery unit into a drug-treatment wing. Demmer recounts that one hospital on the verge of closing transformed itself into an emergency operation center and a new multi-specialty clinic.

Demmer adds that he would like to see improvement in payments for telemedicine services to allow rural hospitals to partner with specialists in urban areas or other states: “In my hospital we have an e-ICU, with specialists in another hospital remotely monitoring our patients in the ICU, and it has been critical in helping keep our ICU staffed and open. We also have an inpatient behavioral health unit that uses telehealth psychiatrists.”

Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Minnesota and Nebraska have laws allowing reimbursement for remote patient monitoring. Leading the way in 2015 was the “Minnesota Telemedicine Act” (SF 1458) that ensures telemedicine parity as well as coverage of “store and forward” telehealth, which involves collecting and sharing clinical information electronically. North Dakota is the only other Midwestern state covering “store and forward,” having added this option in 2019 (SB 2094).

Illinois, Ohio and Wisconsin are the only Midwest states lacking telehealth parity laws, which ensure that virtual care delivery is reimbursed at the same rate as in-person care.

Claudia Eisenmann, CEO of Gibson General Hospital in Princeton, Ind., a specialist in turning around struggling hospitals, agrees with Demmer about the importance of telehealth and says participation in the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact — under which licensed physicians can qualify to practice medicine across state lines, and be reimbursed for their services — is “absolutely essential.”

“With the compact we can access the best specialists across the nation, because we are not going to get these specialists to move to small towns,” she says.

Indiana and Ohio are the only Midwestern states not in the compact.

Recruiting health care providers to rural communities is another area of concern, says Demmer. The shortage of rural healthcare providers is about four times that in metropolitan areas. In addition to rural training tracks in medical school, all Midwestern states provide tuition reimbursement programs, which vary from $20,000 per year for two years in Minnesota to $200,000 for three years in South Dakota.

According to the National Health Service Corps’ 2016 Participant Satisfaction Survey (released in January 2017), these state-funded programs have been extremely successful, with 88 percent of participating professionals still in the rural practice one year after their obligation, and 44 percent remaining for five years or more.