2020 MLC Chairman’s Initiative on Literacy

Wisconsin has new dyslexia law; other states require screenings, interventions and teacher training

In Wisconsin, the path to getting any kind of dyslexia-related bill through the Legislature has never been easy, with bills in various sessions getting caught up in what has been called the state’s “reading wars” over issues such as phonics, whole language and how best to instruct students. But proponents of getting the state, and its school districts, to do more to help young people with dyslexia and related conditions finally found some legislative success in early 2020.

“It’s going to be a very good first step,” Wisconsin Rep. Bob Kulp says of AB 110, which became law in February. “[It] puts dyslexia on the radar screen in our state.”

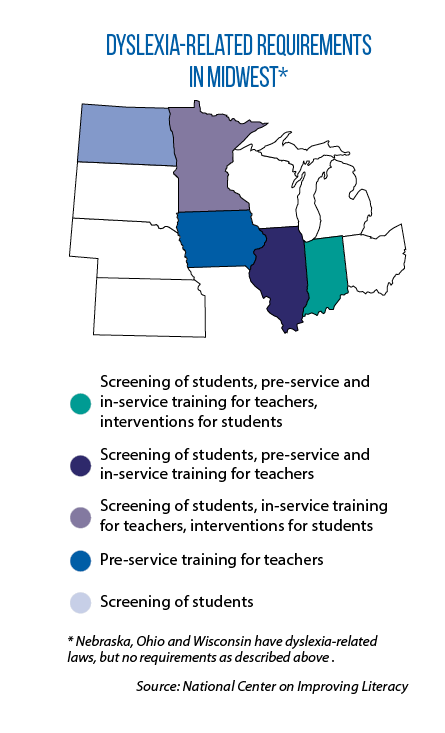

Prior to the bill’s passage, Wisconsin was one of four Midwestern states (Kansas, Michigan and South Dakota are the others) without laws on dyslexia, according to the National Center for Improving Literacy. Much of that center’s research has focused on provisions that require dyslexia-related screenings and interventions by school districts, as well as training for prospective and current teachers.

Wisconsin’s AB 110 includes no such mandates. Instead, the state Department of Public Instruction (DPI) will develop a guidebook on dyslexia and related conditions and then update it every three years. It will include information on how to identify dyslexia and provide students with proven intervention and instructional strategies. An advisory committee will write the guidebook, and Kulp says it will be made up of equal numbers of members from two groups that traditionally have been on opposing sides in the state’s “reading wars.”

“The idea is to throw them in a room together and, with help from the DPI, build a guidebook,” he adds. Once this new resource is complete, Wisconsin school districts must provide a link to it on their websites.

As part of the statute, too, Wisconsin legislators defined dyslexia:

“[A] specific learning disability that is neurobiological in origin … characterized by difficulties with accurate and fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities.”

Kulp is now looking to take additional policy steps — for example, modifying local reading assessments (AB 632) and requiring that each of Wisconsin’s Cooperative Educational Service Agencies, which provide support to K-12 districts, hire a dyslexia specialist (AB 635). His proposals also incorporate some of the state strategies tracked by the National Center for Improving Literacy; AB 604, for instance, would require school districts to have a policy for identifying and helping students with dyslexia. According to the center’s Brian Gearin, among the 50 states, universal screenings and early interventions are the most common policy trends.

“Most states with screening and intervention laws also provide educators with some level of in-service professional development,” he adds. “But in many cases, it is just a one-time event. About a dozen have laws that address pre-service training and educator preparation.”

The prevalence of dyslexia among students varies widely in different studies, but the rate usually falls between 3 percent and 7 percent. Gearin says these students’ reading difficulties often can be alleviated if they are addressed early on. “After that, schools should use evidence-based interventions that correspond to a student’s specific area of need.”

The 2020 Midwestern Legislative Conference Chairman’s Initiative of Michigan Sen. Ken Horn is on state policies to improve literacy.