As they grapple with public health crisis, state leaders have limited budget-balancing options

As most states in the Midwest entered a new fiscal year in July, the unknowns about FY 2021, and beyond, far outweighed the knowns. Will more federal assistance be made available to help close budget shortfalls? How big will those shortfalls be? Will the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic be felt the entire fiscal year?

“It’s been very hard for states to forecast given the uncertainty of the public health emergency,” Shelby Kerns, executive director of the National Association of State Budget Officers, said during a July webinar of The Council of State Governments’ Midwestern Legislative Conference.

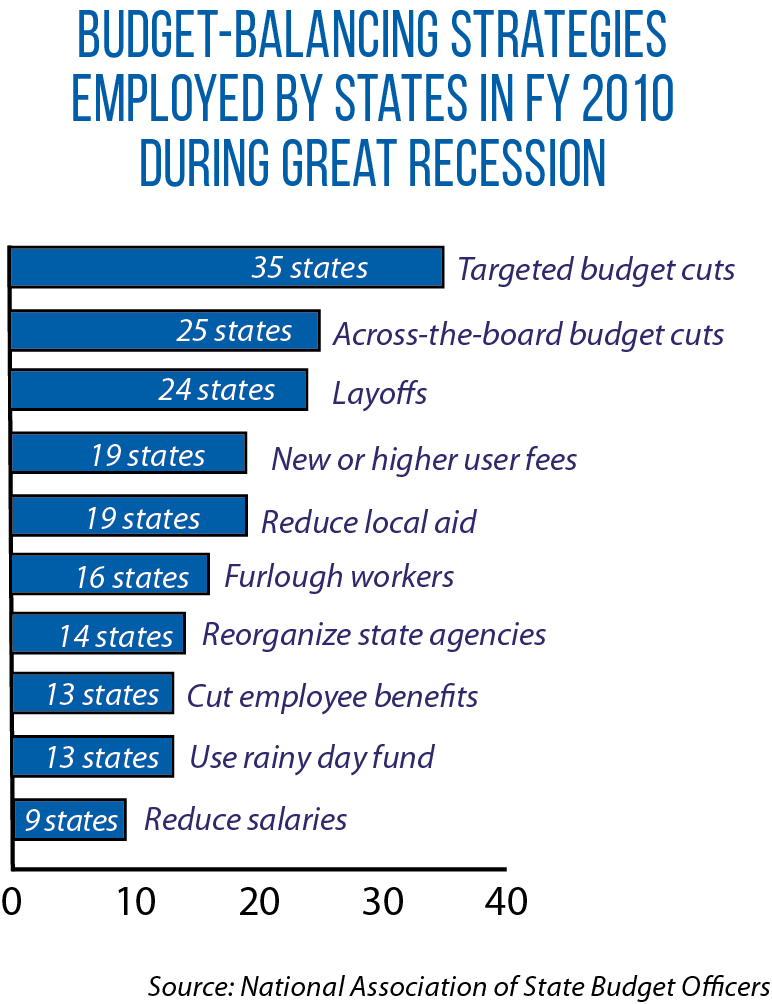

But she told legislators of one unmistakable fiscal reality: “States will be grappling with the impact of COVID-19 for years to come.” The options to fix out-of-balance budgets fall into three broad categories: cut spending, raise more revenue or tap into savings. But some of the specific strategies traditionally used by legislators may not be available this time around. “What’s different about this fiscal crisis is the public health emergency, which can limit or change some of the options,” Kerns said. “In addition to increased spending being required to respond to the pandemic, some cuts may be impossible, or least unwise.”

During the Great Recession, many states cut reimbursement rates for Medicaid providers and reduced aid to local governments, which employ many first-responders and other frontline workers. Would such cuts be wise, or even possible, now?

Similarly, Kerns noted that during the two fiscal years of the Great Recession, state spending on K-12 education fell by nearly 8 percent. Some kind of cuts in this area would seem likely in FY 2021, simply because the funding of elementary and secondary schools takes up such a large portion of spending (more than one-third of expenditures in state general funds). Yet there will be pressures to spend more on education, due to concerns about the impact of this spring’s school closures on academic achievement and the push to boost student access to broadband and e-learning devices.

Paths to balanced budgets

According to Kerns, most governors were asking state agencies to plan for cuts of 4 percent, 10 percent or 15 percent in FY 2021. Projected declines in revenue for the fiscal year have ranged widely in different states, anywhere from 4 percent to 40 percent — a sign of how uncertain this fiscal period is. Also unclear is the extent to which states will get help from Washington, D.C.; during the Great Recession, federal aid helped offset many state budget cuts.

”To date, that aid has been more focused on helping with increased expenditures from the public health crisis and not on assisting states with revenue loss,” Kerns said.

When the pandemic hit, state rainy day funds (both nationally and in some Midwestern states) were at an all-time high. Tapping into these funds will be one budget-balancing strategy for FY 2021. However, rainy day funds alone won’t be enough to fill the large shortfalls in FY 2021, and Kerns added that it’s best not to deplete these savings in a single year.

What about raising taxes?

Kansas Sen. Carolyn McGinn said that option is out of the question in her home state due to concerns about the economic effects. “We have small businesses that are just trying to survive,” she told fellow legislators on the webinar.

View from the Canadian provinces

Also on the webinar, lawmakers learned about the economic slowdown occurring in Canada. In Ontario, in the months of March, April and May, one in three workers either lost their jobs or had their hours cut in some way. Ontario’s year-over-year economic GDP is expected to decline by 9 percent in 2020. But that province’s government has one option not available to the states: Run a deficit. (Every state in the Midwest has a statutory or constitutional requirement to enact balanced budgets.) Ontario’s deficit is projected to be $41 billion, or 5 percent of GDP, David West, chief economist and deputy officer of the Financial Accountability Office of Ontario, told webinar participants.

Provincial law does require the government to have a multi-year plan to balance the budget.