Future of Medicaid being shaped by state expansions, work requirements and new ideas to contain costs

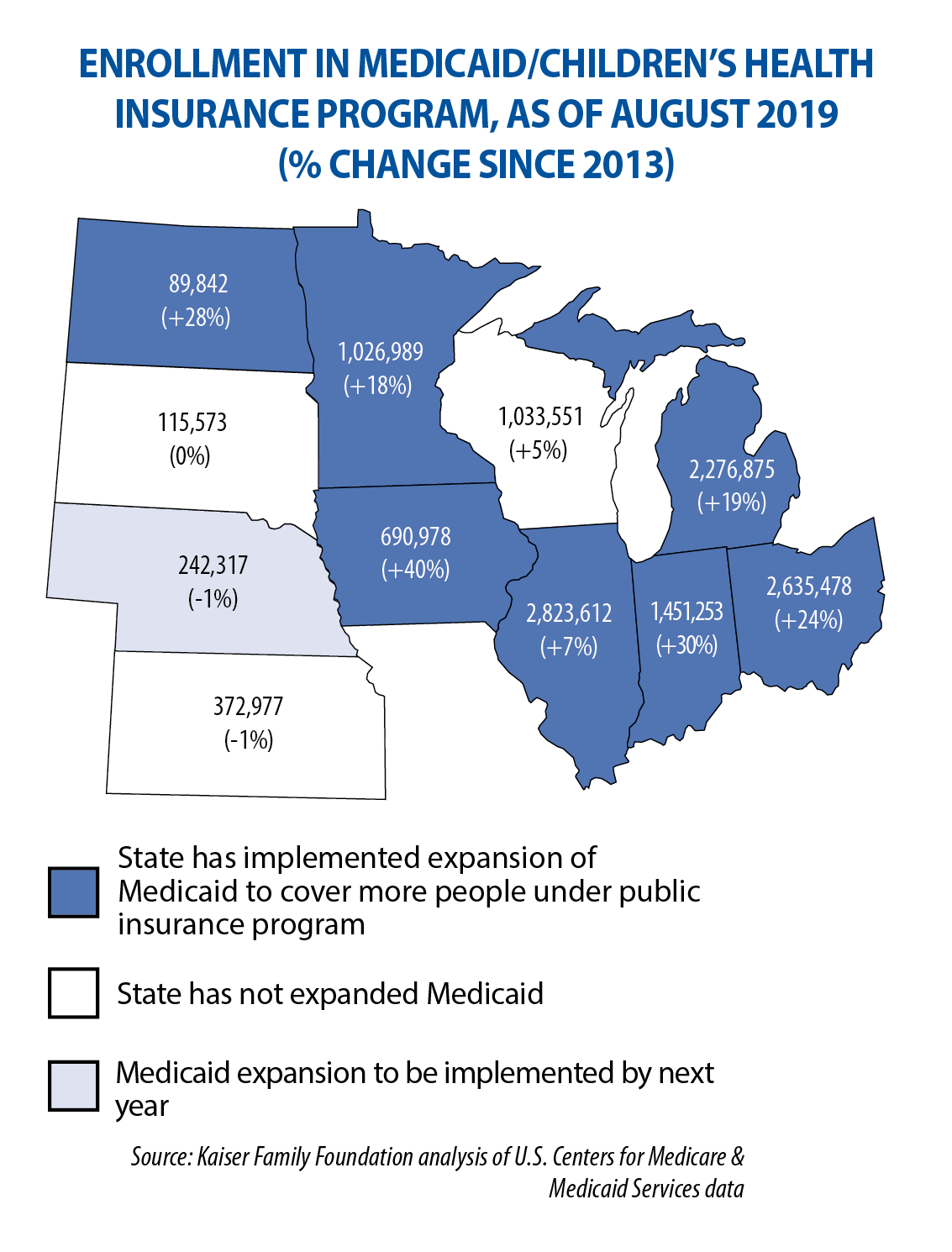

Nebraska close to joining list of expansion states; talks continue in Kansas

Nebraska voters approved the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion in a November 2018 referendum. The state is planning to launch this expansion (to uninsured adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level) in October. Right now, it’s pursuing a federal “Section 1115” waiver, named for the part of the Affordable Care Act that allows a state to include program elements different from what is allowed under federal law — provided the state can show the changes will be successful, yet budget-neutral to the federal government.

is planning to launch this expansion (to uninsured adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level) in October. Right now, it’s pursuing a federal “Section 1115” waiver, named for the part of the Affordable Care Act that allows a state to include program elements different from what is allowed under federal law — provided the state can show the changes will be successful, yet budget-neutral to the federal government.

Nebraska’s proposal creates two tiers of coverage: a “basic” plan for expansion-qualified adults and adults already in Medicaid as parents or caretaker relatives, and a “premium” plan that will include dental and vision appointments and over-the-counter drugs. The premium plan will be available only to people who are working, in school, volunteering or caring for a relative; it comes with an 80-hour per-month work requirement in order to qualify for coverage.

Medicaid expansion remains under debate in Kansas, where Gov. Laura Kelly in September established a committee to study the expansion experience in other states and to outline these findings for consideration during the 2020 legislative session. Kansas is one of three Midwestern states that has not expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act; the others are South Dakota and Wisconsin.

Work requirements in place, but being challenged in recent federal lawsuits

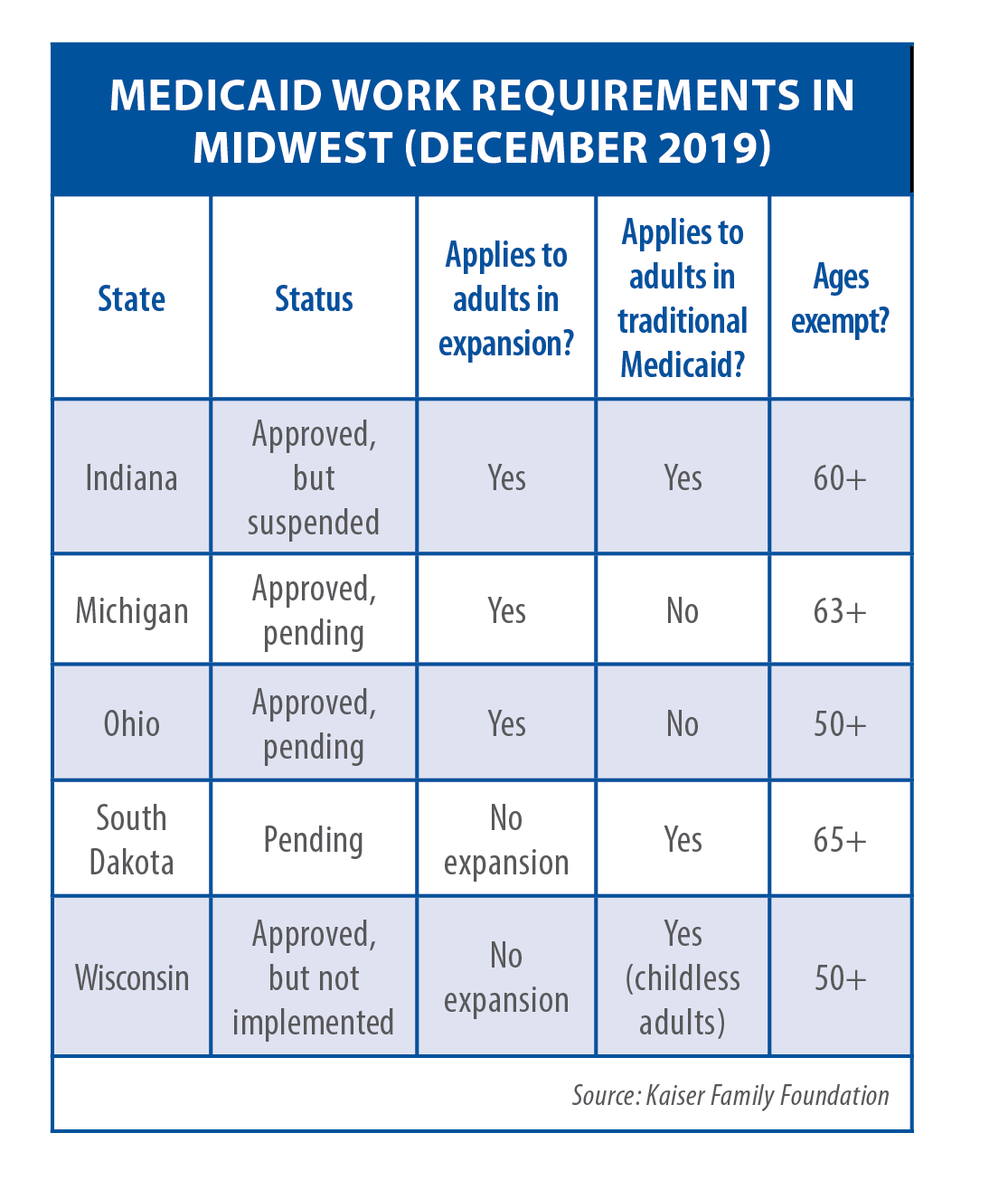

Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, South Dakota and Wisconsin have plans that require, or will require, adults to work in order to be eligible for Medicaid benefits. Ohio, South Dakota and Wisconsin require adults to work at least 80 hours per month. (Ohio’s plan has been approved by the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, but won’t be implemented until 2021.)

Indiana’s and Michigan’s requirements were scheduled to begin in January, but both are subject to federal lawsuits. While details vary from state to state, these laws generally require able-bodied adults who are on Medicaid to work or be in school or in workforce training, volunteer or be looking for a job, be caregiving or in a rehab program (for a certain number of hours per week or month) in order to receive benefits. Exemptions are made for pregnant women (or women who just gave birth), medically frail people, people in rehab, parents of young children, and people under or over a certain age. Indiana’s requirements begin at 20 hours per month and increase to 80 hours after July.

But officials in October suspended implementation pending resolution of a federal lawsuit (Rose v. Azar) alleging the requirements are “categorically outside the scope of” the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ waiver authority under Section 1115, violate federal law, and are “arbitrary and capricious and an abuse of discretion.” No one will lose benefits before the lawsuit is decided, Indiana officials said. In early December, Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer called for postponing implementation of her state’s work requirements, too, several days after a similar lawsuit (Young v. Azar) was filed. Legislation would need to be passed for Michigan’s requirements to be postponed or permanently removed.

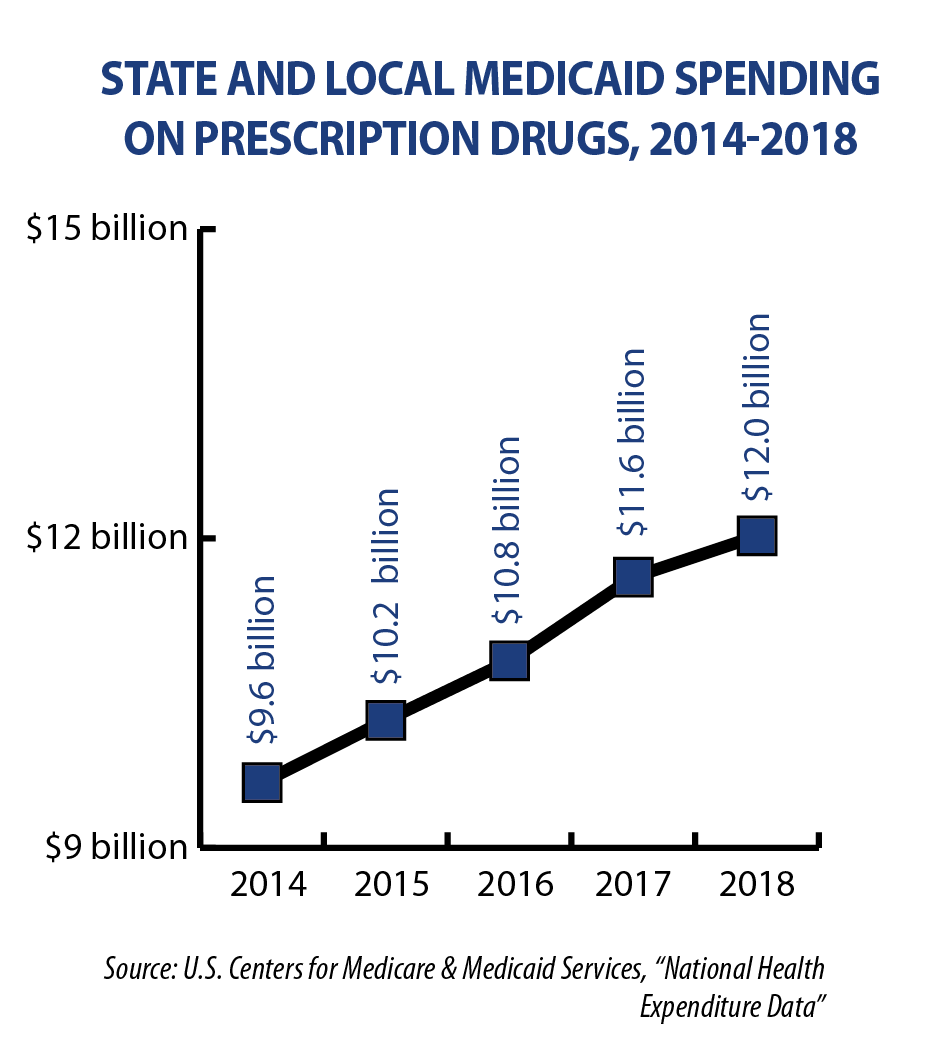

States seek new ways to contain drug costs, improve transparency

States are taking myriad approaches to contain prescription drug costs in their Medicaid programs. Among the policy ideas highlighted in a 50-state survey released in October by the Kaiser Family Foundation:

• Colorado plans to import drugs from Canada for resale to residents, if the federal government allows it. Similar legislation (SB 525) has been introduced in Michigan.

• Massachusetts is negotiating with drug manufacturers on supplemental rebate agreements for the highest-cost drugs. If no agreement is reached, a public process will be used to determine the target value of the drug and improve transparency. Manufacturers also may be referred to the state Health Policy Commission for further accountability. The state anticipates these reforms will save the Medicaid program $70 million in FY 2020.

• New York’s Medicaid drug cap limits aggregate drug costs to an annual trend factor. For each year that costs exceed the allowable cap, the state negotiates enhanced rebates with the drug manufacturer and may refer drugs to the Drug Utilization Review Board for additional review.

Among Midwestern states, Kansas may place a temporary prior-authorization requirement on new drugs that meet certain criteria until the state’s Drug Utilization Review Committee is able to adopt a more permanent policy. States are also scrutinizing pharmacy benefit managers. The position is designed to leverage the aggregate purchasing power of health insurance policyholders by negotiating price discounts with pharmacies or prescription home-delivery services, and rebates from pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Kansas, North Dakota and Ohio regulated them before 2019 and were joined this year by Nebraska and South Dakota. Legislation to regulate pharmacy benefit managers and require annual price transparency reports remains pending in Michigan and Wisconsin. Michigan also is proposing to eliminate the use of Medicaid health plans’ pharmacy benefit managers and instead use a fee-for-service model with a single PBM from the state.