Race to zero: Proposed federal rule, laws in states such as Minnesota are targeting a full replacement of lead service lines over next decade

Each policy conversation about lead in drinking water begins with a shared foundation: there is no safe level of lead in the human body. It is a persistent public health issue, one that for generations has disproportionately affected young people, particularly those living in underserved communities. No immediate solution is in sight, but over the past few years — in response to the devastating Flint water crisis in Michigan and other high-profile cases of lead exposure in communities — there has been a swell of new laws and regulatory activity.

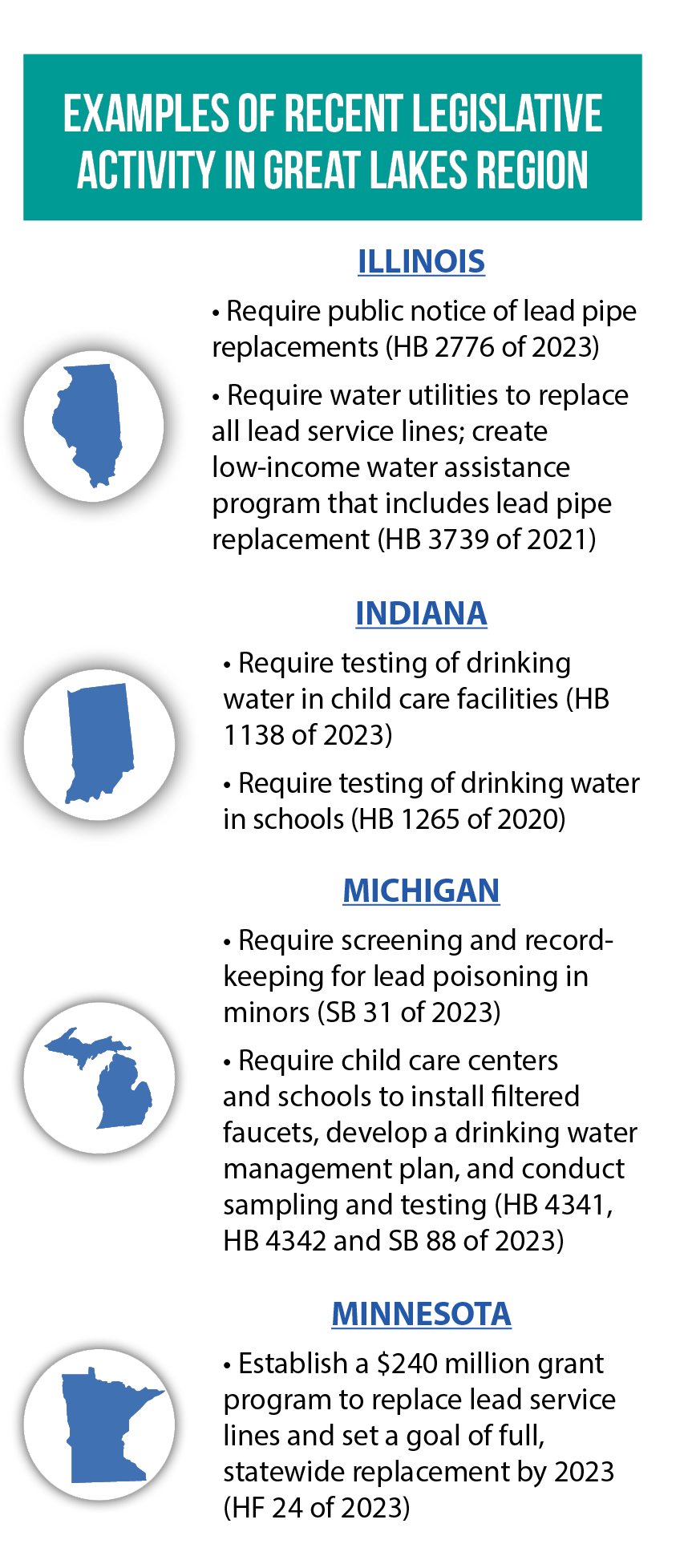

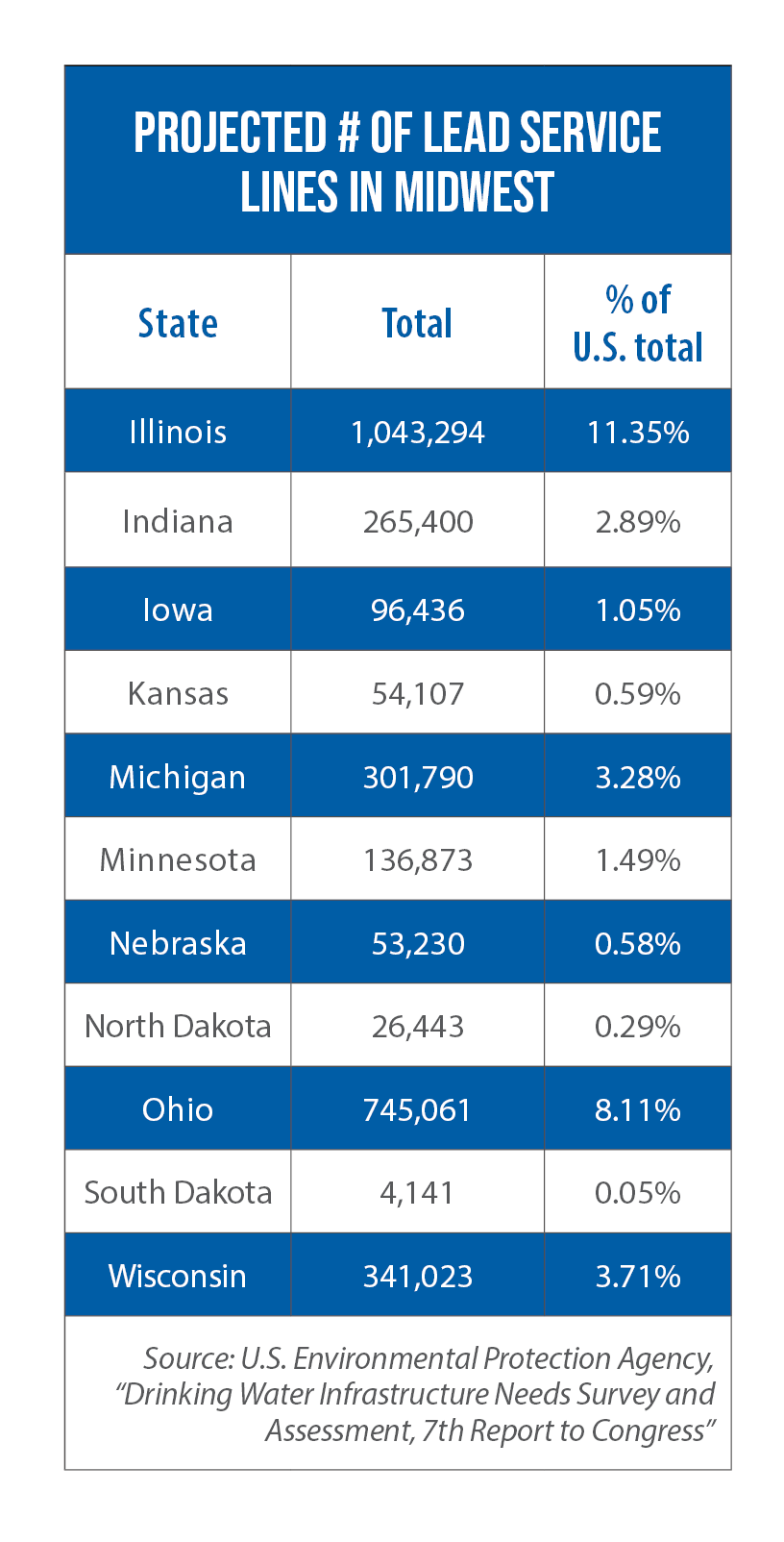

It’s part of a “race to zero”: eliminating the threat of lead in drinking water. Parts of the Great Lakes region are most in need of these protections and improvements to the water infrastructure (see table).

It’s part of a “race to zero”: eliminating the threat of lead in drinking water. Parts of the Great Lakes region are most in need of these protections and improvements to the water infrastructure (see table).

“Every dollar spent on removing lead in drinking water puts two dollars back into the economy,” says Minnesota Rep. Sydney Jordan, noting a 2019 study from her state’s Department of Health.

That study pegged the cost of removing the two most significant sources of lead in Minnesota’s drinking water (lead service lines and plumbing fixtures) at up to $4.12 billion over a 20-year period, but the benefits at as much as $8.47 billion. This return on investment, the study’s authors say, comes from ending Minnesotans’ exposure to lead in drinking water. For example, exposure is linked to developmental delays and reduced cognitive functioning, resulting in less productivity and fewer earnings over a person’s lifetime.

New grants in Minnesota

Last year, Jordan and other Minnesota legislators established a new statewide goal: remove all lead service lines in the state by 2033. The same legislation, HF 24, also created a $240 million grant fund to pursue work related to this goal.

Priority is going to the removal of lead pipes in areas where young people have elevated levels of lead in their blood, and where there are schools, child care centers or “other properties … used by disproportionately large numbers of children.” Priority also is going toward work in disadvantaged communities.

Priority is going to the removal of lead pipes in areas where young people have elevated levels of lead in their blood, and where there are schools, child care centers or “other properties … used by disproportionately large numbers of children.” Priority also is going toward work in disadvantaged communities.

“Environmental justice is a top priority for [us], so we want to target areas where lead exposure is greatest,” says Jordan, chief author of HF 24.

The grant program also addresses a common financial hurdle for fully replacing lead service lines. Typically, part of a lead service line is owned by the public utility; the other by the homeowner. To fully replace that line, a homeowner can be burdened with thousands of dollars in replacement costs.

But with Minnesota’s new grant program, the state covers all of the replacement costs for private service lines (and 50 percent for the publicly owned portion).

Big changes in federal rule

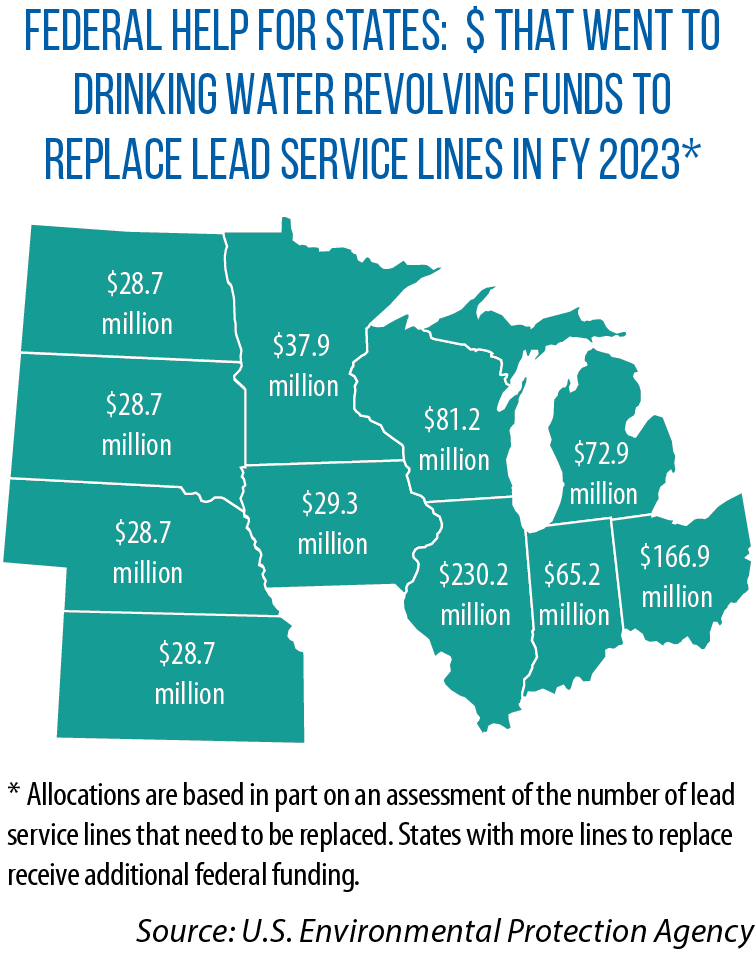

Minnesota’s investment is coming at the same time that states are getting historic amounts of federal assistance to remove lead service lines, via the Drinking Water State Revolving Loan Fund (see map) as well as $15 billion over the next five years from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

Still, current levels of federal support fall short of the costs of full replacement, and under a proposed rule change of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, most water systems would need to remove lead service lines over the next decade.

This proposed revision of the Lead and Copper Rule is expected to be finalized sometime in 2024. Another key provision in it would lower the “lead action threshold” from 15 parts per billion to 10 ppb. This threshold triggers requirements regarding public notification and remediations to reduce lead exposure.

The accelerated replacement of lead pipes has been a policy priority of groups and coalitions such as the Great Lakes Lead Elimination Network. But Melissa Cooper Sargent, who co-manages this regional network through her work at the nonprofit, Michigan-based Ecology Center, also notes there are exceptions in the proposed federal rule to account for the pace of replacement and for large water utilities with high numbers of lead pipes.

“A large city like Chicago would maybe even have 40 years to replace those pipes; that’s just too long … for people to continue to be exposed to lead,” she says.

More testing in schools

Minus a full replacement of lead service lines, state laws that require an inventory of lines as well as a testing of drinking water can help identify areas in need of lead-eliminating filters and other immediate remediations.

In Indiana, for instance, Rep. Carolyn Jackson has been part of past legislative efforts that now mandate the testing of drinking water in schools (HB 1265 of 2020) and child care facilities (HB 1138 of 2023).

“The state of Indiana has not put any money in to help cover testing and remediation of lead in drinking water; the money we get is coming from the EPA,” says Jackson, who has introduced measures for a new state grant program for schools.

Some of these federal dollars are coming from the EPA’s Voluntary School and Child Care Testing and Reduction Grant Program. To date, program recipients have tested for lead in more than 12,500 U.S. schools and child care facilities.

This grant program also is being used to reach tribal schools and child care centers. The Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Epidemiology Center coordinates much of the work being done in Wisconsin and Minnesota.

“We work closely with the states to make sure we’re not duplicating services and helping each other fill gaps,” says Jacob Rimer, a public health specialist with the center.

Challenge in Canada

In 2019, the Government of Canada released guidelines on lead in drinking water, recommending corrosion control of lead pipes and/or lead service line replacement as remediation measures, as well as lowering the action threshold from 10 ppb to 5 ppb.

However, the province of Ontario’s action threshold remains at 10 ppb.

“Health Canada guidelines are not enforceable in Ontario,” Ontario Water Works Association executive director Michele Grenier says. She does not expect the province to adopt the federal guidelines; Québec did so in 2019.

As of late 2023, 21 municipalities in Ontario had filed lead control plans since 2007. Seven of those communities opted for a strategy of total lead service line replacement and eight are pursuing corrosion control. Six are pursuing a combination of these strategies.

The replacement of the privately owned portion of lead service lines also is an ongoing challenge in Canada. “There needs to be a funding source for homeowners to access to help them get it done. … The uptake on [loan and repayment plans] is incredibly low,” Grenier says.