States at center of nation’s response to COVID-19 pandemic, and work has just begun

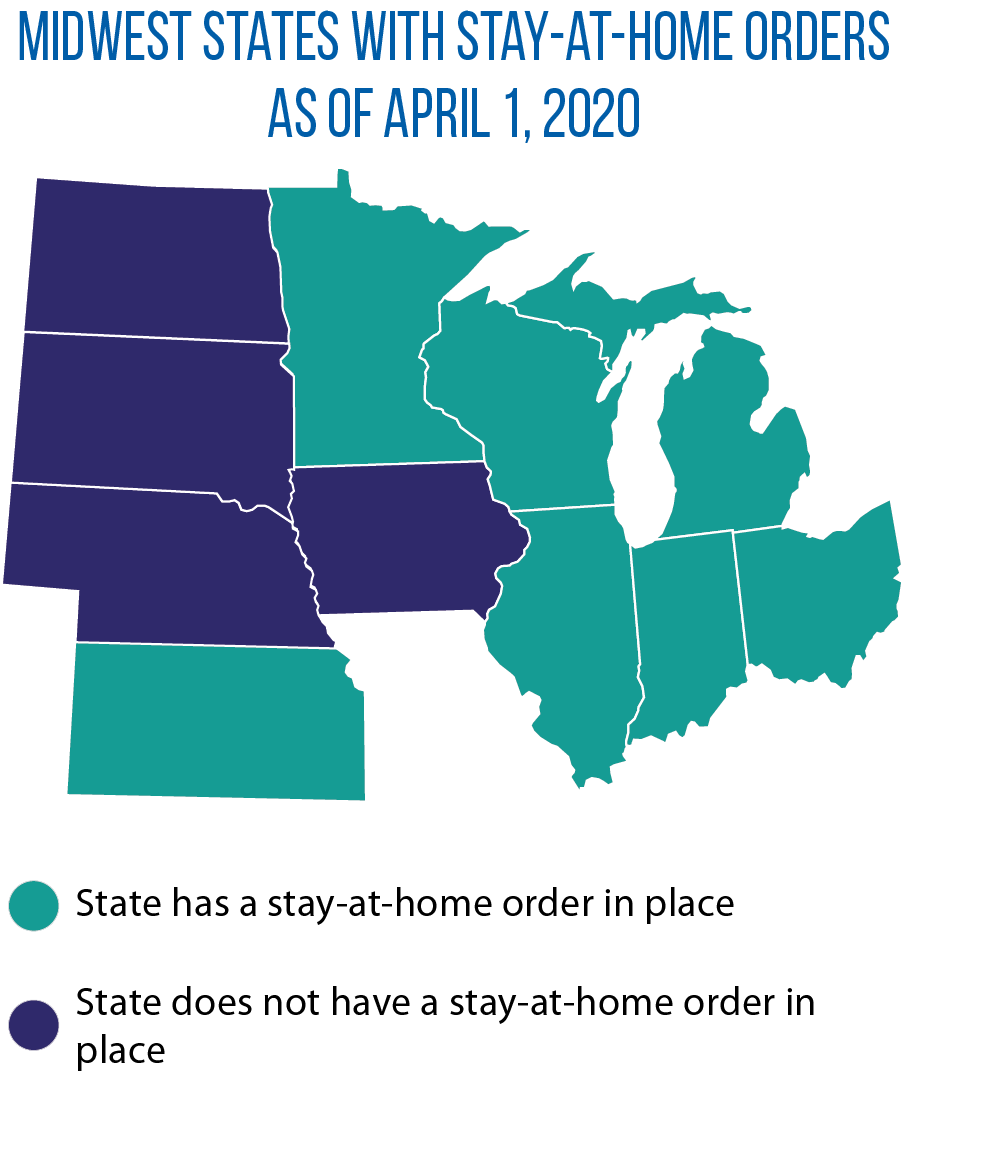

The scale and scope of the COVID-19 pandemic has turned a spotlight on the role of states in responding to a new public health emergency in a manner quite unlike a tornado, flood or even recent viral concerns such as H1N1 or Ebola. By April, all states and provinces in the CSG Midwest region had declared either states of emergency or public health emergencies. In many, governors or premiers had enacted “stay-at-home” or “shelter-in-place” orders for the first time in living memory.

For state legislatures, the early response centered on working with their governors (oversight, consultation, etc.) and providing emergency funding where it was needed most.

“It’s not our job to micro-manage the response, but to understand what the professionals already have in place, what they need, and what they say we’ll need next,” Minnesota Senate Deputy Majority Leader Michelle Benson says. “Our job is to listen to them and have some clear conversations about how we’re going to help.”

In Minnesota, legislators acted quickly with $530 million in appropriations

Benson sponsored one of the two major bills that shaped Minnesota’s initial legislative response to the pandemic: SF 4334 and HF 4531. Signed into law in March, the measures reflect not only the unprecedented impact of the COVID-19 outbreak, but also the critical role of states in managing a public health crisis.

Under SF 4334 (of which Benson was a lead sponsor), the Legislature appropriated $200 million for emergency investments in the state’s public health infrastructure — for example, money for providers to build temporary hospitals, hire additional staff, add testing capacity, purchase medical equipment and establish areas to isolate or quarantine patients. The same measure appropriates money to help medical facilities, nursing homes and pharmacies prepare for an outbreak. Lastly, it makes COVID-19 consultations and treatments via telemedicine eligible for health insurance coverage.

The second measure passed by the Minnesota Legislature was even larger and broader in scope. Under HF 4531, the state is directing $330 million to address a host of pandemic-related impacts. Child care centers became eligible for emergency state grants. Homeless services and food banks got additional state support, and small businesses received loan assistance. The bill also set aside $1 million each for the state’s 11 Native American tribes for their COVID-19 responses.

The largest part of the spending, though ($200 million), has gone to as “COVID-19 Minnesota Fund” to pay for undetermined costs to “protect Minnesota citizens from the COVID-19 outbreak” and “maintain state government operations throughout the duration of the peacetime emergency.”

The money is being spent via state agencies, but the Legislature maintained an important oversight role: Expenditures must be approved by a commission of legislative leaders. The fund expires on May 11, with any unspent money going back to the general fund.

Thinking ahead by looking back: plans for an ‘after action’ review

Beyond the initial response to the crisis, Sen. Benson says she and other Minnesota legislators already are planning an “after-action” review of the state’s — and the Legislature’s — response to the COVID-19 pandemic to be better prepared for the next time.

One realization so far is the need for some sort of legislative emergency response “advisory commission” to give the governor emergency spending authority in narrowly defined situations, she says, noting the next emergency might not happen while legislators are in session.

Another overarching concern of Benson’s is the state’s — and nation’s — ability to respond to the need for more medical supplies. “We have to change our supply chain [for medical and pharmaceutical manufacturing],” Benson says. “Already what we’ve learned is we’re far too dependent on China for our manufacturing.”

“I think that will be a significant part of the conversation when we get through this,” she adds.

South Dakota, Nebraska among other states to take quick legislative action

Other part-time state legislatures in the Midwest also faced the pressures of addressing the impact of the coronavirus outbreak, with limited time to do so (either because of session limits or the inability to meet because of the risks of COVID-19 infection).

In South Dakota, on their last day of regular session (a day traditionally used to act on gubernatorial vetoes), legislators approved nine COVID-19-related emergency bills. Among the measures:

- creating a $10.5 million revolving loan fund for small businesses (SB 192),

- expanding eligibility for unemployment insurance for people who lost jobs because of the pandemic

(SB 187), and - allowing the governor to waive the state’s minimum instructional hours for schools (SB 188).

Nebraska senators acted quickly as well with unanimous approval in March of LB 1198, which appropriates $83.6 million for COVID-19-related costs. That money will help various entities in Nebraska purchase personal protective gear for workers, bolster capacity at testing labs, and establish a statewide communication system to share information on response efforts.

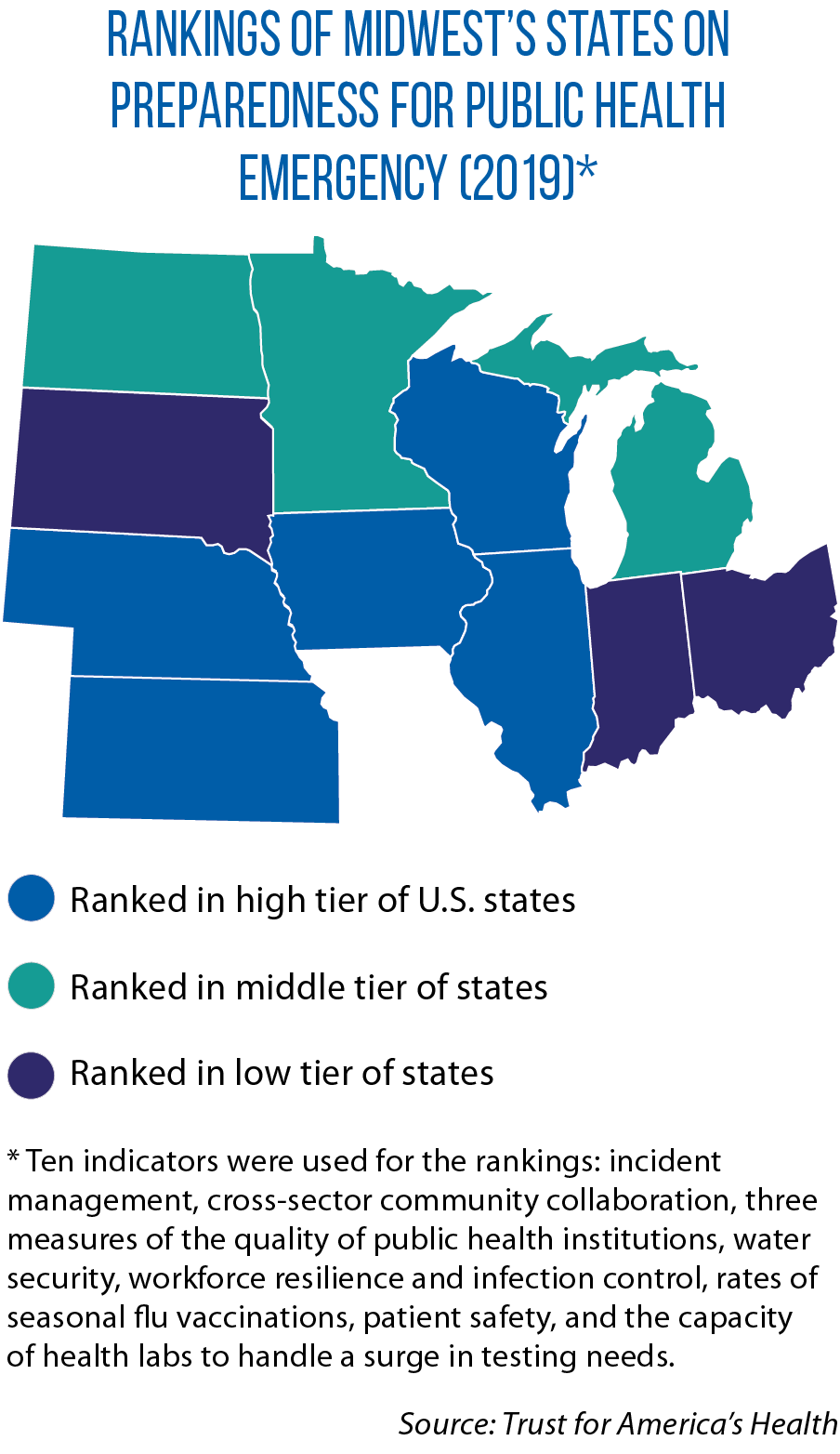

National study ranks states on preparedness for health emergencies

States are much better prepared to respond to emergencies of all kinds as the result of advances made after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, says John Auerbach, president and CEO of the Trust for America’s Health, which in February released a report on the states’ readiness for public emergencies. For example, he says, states are now required under federal law to develop and update “all hazards” emergency response plans. In addition, Auerbach says, “there have been both real opportunities to respond to emergencies over the last several years — H1N1, Zika, measles, etc. — and [to conduct] preparedness drills.”

The Trust for America’s Health study, though, did point to variances in the readiness of states to respond to crises such as diseases, natural disasters and bioterrorism (see map). It used 10 indicators to evaluate states, including:

- the ability to expand health care capacity via adoption of an interstate compact on nurse licensure;

- the level of participation by hospitals in health care coalitions that coordinate responses to a crisis and manage a surge in medical needs;

- planning by public health labs to boost testing capacity in an emergency;

- the quality of health care providers on measures of patient safety;

- the size of states’ public health budgets; and

- seasonal flu vaccination rates.

States should fully fund emergency preparation in their health budgets on an ongoing basis, Auerbach says, adding that the states which did so before the COVID-19 outbreak are the ones responding best to it.

“You can’t prepare for an emergency after the emergency arrives,” he says.

Jon Davis serves as staff liaison to the Midwestern Legislative Conference Health and Human Services Committee.