Illinois laws encourage local food production and sales, analyze gaps in agriculture-based opportunities

Soon after joining the Illinois General Assembly (in late 2015), Illinois Rep. Sonya Harper began focusing on what she calls “localizing our food shed.” It’s why a representative from the Midwest’s largest city, Chicago, has found herself sponsoring multiple agriculture-related bills, and she says events of the last year have only sharpened her interest in this policy area. “If the pandemic showed us one thing, it was the importance of our food supply.”

Among her legislative goals: boost local economies, and improve residents’ health outcomes and economic opportunities. Most recently, too, Harper helped get legislation passed to take a closer look at economic obstacles for farmers — particularly those who have faced historic disadvantages.

Urban ag zones and health food incentives

One of Harper’s hopes is that urban agriculture becomes part of Illinois’ “localized food shed.” She sponsored legislation three years ago allowing Illinois jurisdictions to create urban agricultural zones, with a mix of tax benefits and savings on water rates for individuals and organizations that grow agricultural products within a municipality’s boundaries. “[It] provides an incentive to revive vacant lands and address food desert areas,” Harper says.

Also in 2018, the General Assembly established the Healthy Food Incentives Fund. The bill provides $500,000 (subject to appropriation) to double the amount of benefits available from the U.S. Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program; to qualify for these benefits, purchases must be made at farmers’ markets or other direct-to-producer venues.

Study of disparities in agriculture

Another agriculture-related bill, but one with a much different purpose, became law in Illinois earlier this year. Sponsored by Harper, the Farmer Equity Act (SB 1792) requires a state study of disparities between Black and White farmers. For example, what are the gaps in income levels, land ownership, and access to loans and capital? A final report is due next year. Other socially disadvantaged groups of farmers may also be part of the study.

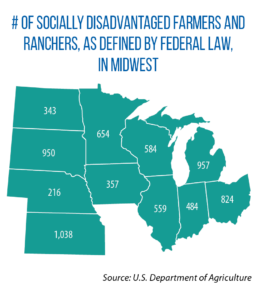

Federal law defines socially disadvantaged farmers and ranchers as those who have been subjected to racial or ethnic prejudice “because of their identity as members of a group without regard to their individual qualities.” Illinois’ legislative actions occurred at around the same time that the U.S. Congress passed the American Rescue Plan, which sets aside $5 million in aid for minority farmers. That provision, though a small part of the federal law, has received considerable attention, as well as some criticism.

However, proponents say the new aid program rightly recognizes the impact that decades of discriminatory government policies have had on farmers of color. For example, minority farmers were locked out of the first Agricultural Adjustment Act from the 1930s, limiting their ability to access credit and markets. Likewise, loans and other support from the U.S. Department of Agriculture were often delayed or denied to people of color.

U.S. Black farmers, who make up 25 percent of socially disadvantaged farmers, have lost more than 12 million acres of farmland over the past century. And only 45,000 of the 3.4 million farmers today are Black; that’s down from 1 million a century ago. The American Rescue Plan provides debt relief for USDA loans to socially disadvantaged borrowers. It also provides grants and loans to improve land access and establishes a racial equity commission within the USDA. In Illinois, meanwhile, legislators will await their state-specific study on racial and ethnic disparities within agriculture.