Strong fiscal conditions help states boost funding for schools in 2021

Michigan closes ‘equity gap’ and Ohio enacts new aid formula; challenges for states remain in adequately funding supports for at-risk students

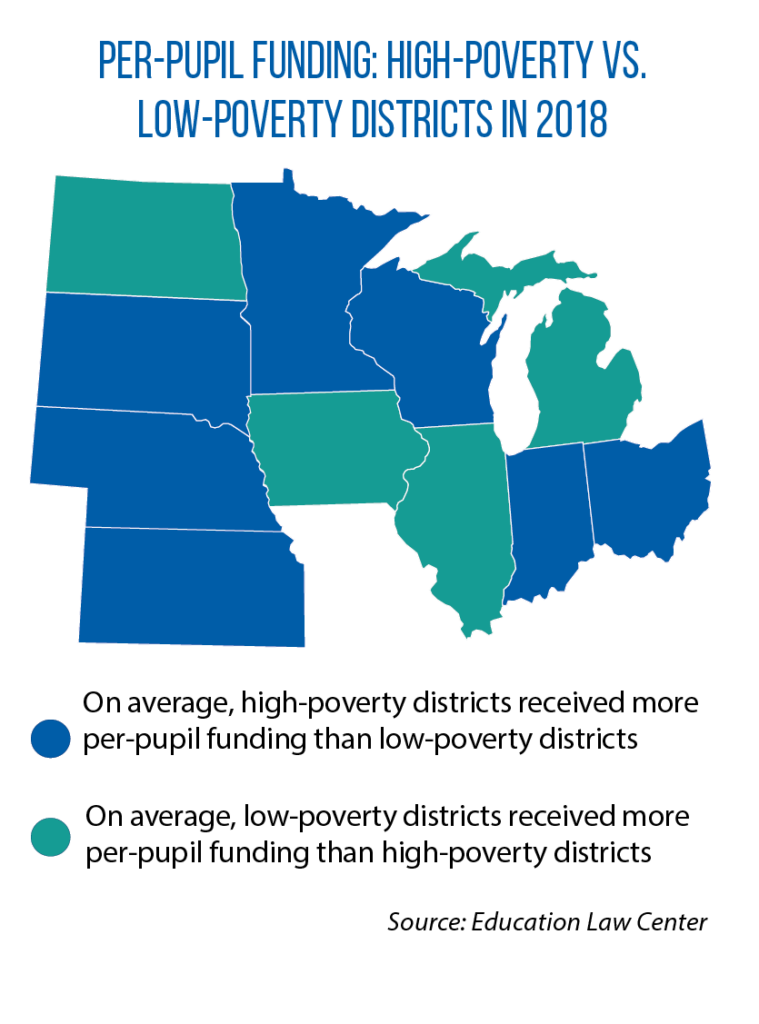

For many years, Michigan legislators have been chipping away at a persistent disparity in how the state’s schools are funded. It is known as the “equity gap”: higher-wealth districts with greater amounts of per-pupil spending than those of their lower-wealth counterparts.

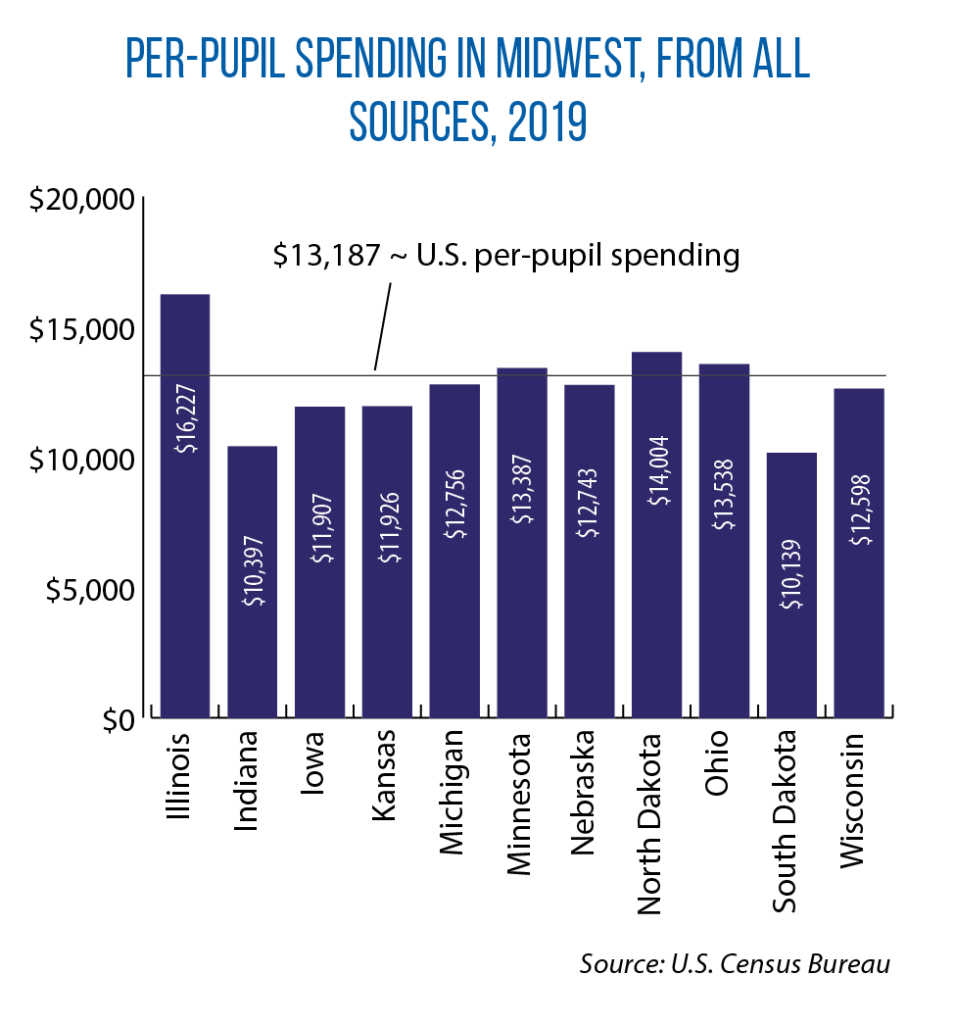

Though in part the legacy of an old system largely reliant on local property taxes, the gap continued long after enactment of a new funding model (added to the state Constitution in 1994) that had the state take over the funding of school operations. This year, with Michigan’s fiscal health strong, a bipartisan budget agreement was reached to spend $723 million to finally close that gap, with a disproportionate share of new state dollars going to lower-funded, lower-wealth districts. All districts will now receive $8,700 per-pupil — a milestone that both Democratic  Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and the Republican-led Legislature hailed as “historic.”

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and the Republican-led Legislature hailed as “historic.”

“It’s been a priority of mine since I got in the Legislature,” says Sen. Wayne Schmidt, a state legislator since 2009 who represents a part of Michigan with some of those traditionally lower-funded schools.

“It’s going to make a big difference. Yes, the problem was acute in northern Michigan and the Upper Peninsula, but you also see the gap across the state, including Detroit Public Schools. Closing it means we have more money to attract and retain quality teachers, and to make improvements in the technology of our classrooms.”

A year ago, few would have predicted that Michigan would be in a strong enough fiscal position to close that gap as early as 2021. Amid a collapsing state and national economy at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Schmidt says, the talk had been of potential cuts in school funding.

“As quickly as some of our revenues were drying up, we saw some rebounds later on that were beyond our beliefs,” he says.

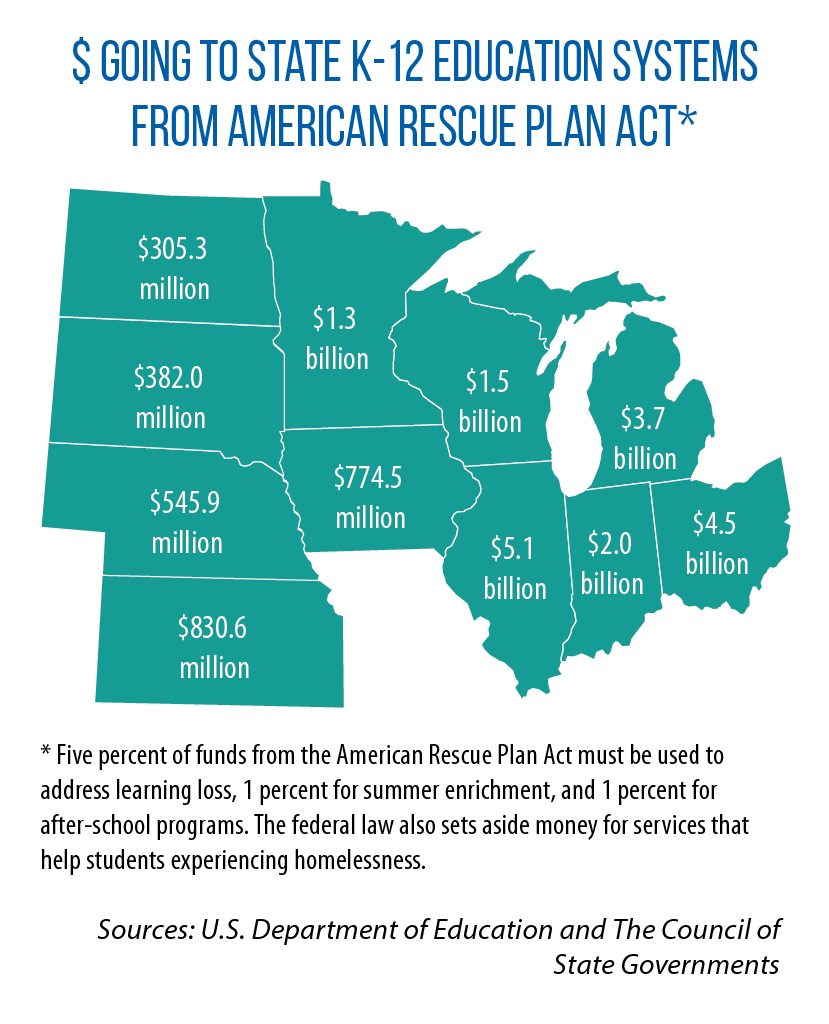

Michael Griffith, a senior researcher and policy analyst for the Learning Policy Institute, says it’s been a roller-coaster period across the country for school funding and related state policies. First, there were big fears about the pandemic’s impact on school finances, but what followed was an economic recovery and an unprecedented federal relief package. The American Rescue Plan Act alone sets aside $123 billion for states and school districts to spend on education between now and 2026. (Michigan is using own-state funding to close the equity gap.)

“Coming up with plans and recommendations on how to spend their share has been so overwhelming that it’s taken up everyone’s time [on school funding],” Griffith says. “Just now, in the last couple of months, states have had some breathing space to start thinking about some of the areas they were thinking about prior to the pandemic.”

‘Fair funding’ in Ohio

One state that seemingly got a head start is Ohio.

As in Michigan, legislators in Ohio are putting more money into K-12 schools, an increase of 8.7 percent this biennium, according to Gov. Mike DeWine. And the General Assembly also tackled a pre-pandemic priority for many Ohio school administrators and legislators: an overhaul of the school funding formula.

Enactment of HB 110 marked the culmination of years of work in developing what’s known as the “Fair School Funding Plan,” says Katie Johnson, deputy executive director of the Ohio Association of School Business Officials.

Yes, improved fiscal conditions helped get this funding overhaul to the finish line. But Johnson says the real key to success was the process established from the start by two legislators, one Republican (Rep. Bob Cupp, now speaker of the House) and one Democrat (Rep. John Patterson, since term-limited out of office).

“They were committed to it being a bipartisan effort, and they brought in a working group of practitioners, local superintendents and school treasurers, at the very beginning in order to develop the plan,” Johnson says.

“That was the key. They all rolled up their sleeves and dug into the details, and developed the formula together.”

3 notable reforms in Ohio

Johnson points to three fundamental changes in Ohio’s new funding formula.

First, she says, it better accounts for the actual costs of providing an education and making that the basis of the state’s statutory per-pupil funding levels. For example, how much must a district spend to have class sizes of 23 in the younger grades or 27 in high school, to hire and retain a sufficient number of special education teachers, and to provide enough student supports (guidance counselors, librarians, etc.)?

The old model did not address those kinds of questions in any kind of rational or systematic way, Johnson says.

In contrast, the new one does. To determine each district’s “base costs,” the formula uses factors such as student-to-staff ratios; the average statewide salaries of teachers and other school employees (from superintendents on down); and each district’s expenses related to technology, building operations and employee benefits.

Secondly, legislators crafted a new way of “equalizing” state funding, a way to ensure lower-wealth districts receive more money from the state in order to reach per-pupil funding levels that cover their base costs. Two factors now will be used to determine the relative wealth of each district: property values and the income levels of residents.

If the school funding formula is fully implemented over the next six years, the average per-pupil funding level in Ohio will reach $7,200. That compares to $6,020 during the last school year, according to the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

Johnson says the third big change involves the funding of charter schools and scholarship programs for students to attend private schools. The state now will directly provide these dollars, rather than the previous approach of deducting a portion of the aid going to local public school districts.

‘Is your system balanced?’

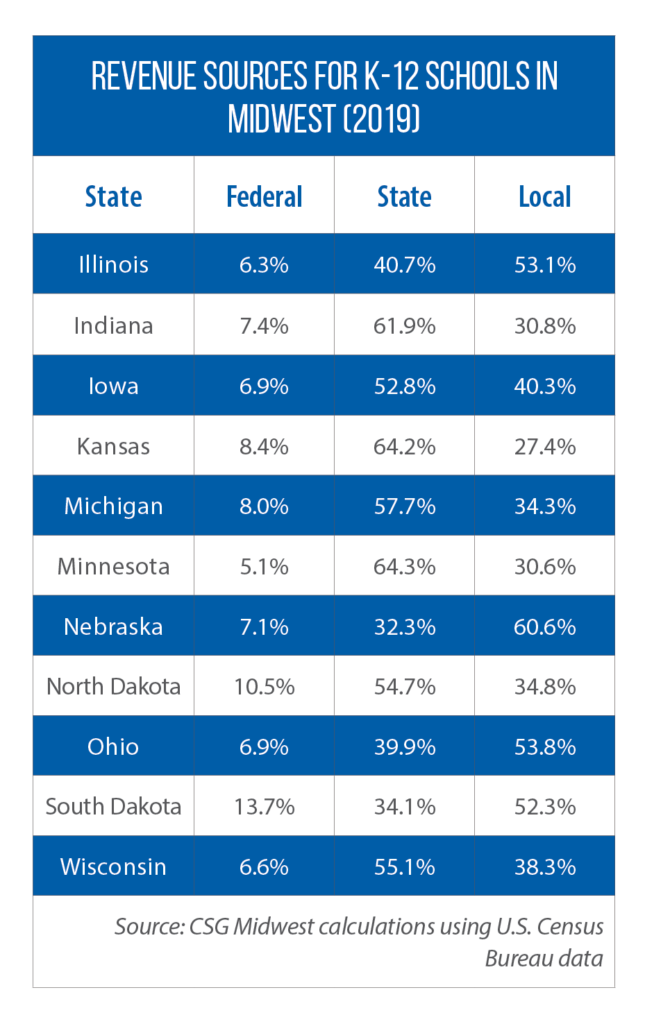

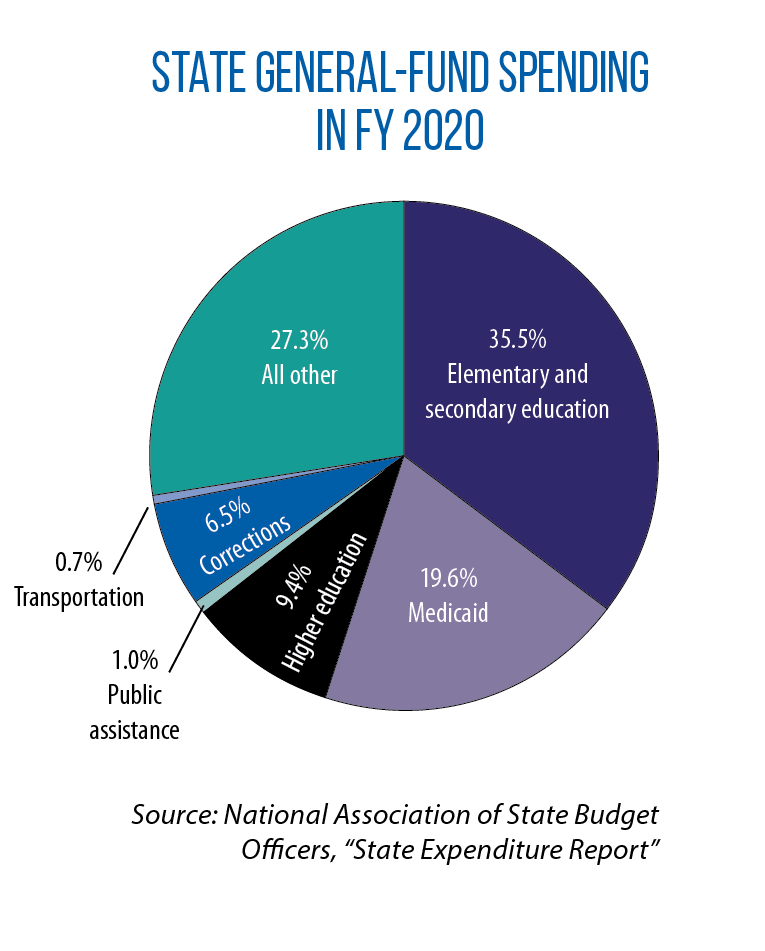

In every state, in every legislative year, the funding of K-12 schools is a high priority for lawmakers. It makes up more than one-third of state general-fund spending, according to the National Association of State Budget Officers. Though exactly how schools are financed can vary considerably from state to state (local vs. state share, details of the funding formulas, etc.), Griffith says there are some underlying principles that should guide all legislatures.

“Are you taking care of everyone?” he says. “Is your system balanced so that every kid gets an adequate education?”

He notes that in his home state of Colorado, the property value of a single home in the town of Aspen can be equal to the property value of entire districts.

“For a state, then, you’re getting the balance right when you have a school district like Aspen covering almost all funding itself, and then you’re devoting the state dollars to boost up the low-wealth districts,” he says. “Because there are places that just don’t have any wealth, and they are struggling.”

The new formula in Ohio and a closing of the equity gap in Michigan are examples of states trying to find a better balance in school funding.

That work is far from done. In Ohio, for example, it remains to be seen whether the legislature can or will fully implement the Fair School Funding Plan over the next six years. HB 110 only commits to using the new formula for the next two years, and more state dollars will be needed in future budgets to reach the average spending level of $7,200 per pupil.

According to Michigan State University professor David Arsen, Michigan’s foundation formula for schools has long failed to recognize the costs of providing an adequate education, or to account for the variance in these costs across districts — greater transportation expenses in rural areas, for example, or the additional resources needed in schools with larger numbers of English language learners, special education students, or young people at risk of falling behind or failing.

Outside its unweighted foundation formula, Michigan does provide additional financial supports for higher-need schools and students, and its recently enacted education budget includes new money for school-based mental health programs as well as for districts to hire additional counselors, psychologists, nurses and social workers.

Lastly, more money will to go Michigan’s Great Start Readiness Program, a preschool initiative for 4-year-olds who are from lower-income families or who are at risk of school failure (due to neglect, a diagnosed disability, a developmental delay or other factors). Gov. Whitmer says the program can now expand to enroll 22,000 more children, ensuring preschool access to all who qualify.

In Ohio, extra aid goes to schools based on their number of distinct student populations: gifted, low-income, special needs and English language learners. What’s new in HB 110 is dedicated funding in the formula for districts to provide physical and mental health services, after-school programming and family supports.

Multiple needs, weights

Looking ahead, Griffith expects states across the country to focus more on better serving at-risk students. That means clearly defining what “at risk” means, better identifying students in need of additional supports, and then providing adequate levels of funding.

“What I’m starting to talk to states about is when you think about at-risk, think about it as levels,” he says.

“So maybe you have a general at-risk student, but then you’re going to provide more resources for kids with higher levels of need. Take, for example, foster youths experiencing homelessness or migrant student populations.

“They’re going to require all the wrap-around services. You have kids where the school is worried about finding them shelter for the night, or getting them food services.”

The way a state funds its schools, he adds, goes a long way in determining whether these students receive the supports and services that put them on a path toward educational success.

“My hope is that [legislators] will look at the research out there and then change at-risk funding accordingly, so that they do not have a single weight for ‘at risk’ but instead multiple weights based on student needs,” Griffith says.