Year of tax cuts has included plans to move toward a flat income tax in two Midwest states, and targeted relief for working families in others

Most states in the Midwest, in some way, cut taxes as a part of this year’s legislative sessions. One that could not was North Dakota, where the state’s part-time legislature only convenes in odd-numbered years.

But several of the state’s top political leaders appear eager to join the tax-cutting trend in early 2023, unveiling a plan this summer that they say would be the largest income-tax reduction in North Dakota history. Their vision is for North Dakota to move away from its five-tiered, graduated income-tax system (the current top rate is 2.9 percent, lowest among the 50 states) and replace it with the lowest flat tax rate in the nation, 1.5 percent. The plan also would eliminate all income taxes for individuals with adjusted incomes of up to $54,725 a year or joint filers with earnings of up to $95,600.

North Dakota Sen. Scott Meyer says this change would mean no income tax at all for 60 percent of the state’s taxpayers, and an even higher percentage would be fully exempt in legislative districts like his that have higher numbers of low- and middle-income households.

The cost to the state: an estimated loss of $500 million during its two-year budget cycle. That equates to about 10 percent of North Dakota’s total general fund budget in 2021-2023 ($4.99 billion).

“Right now, our state is a little flush with funds due to the increase in oil prices; we’ve been very fortunate with our abundance of resources,” Meyer says. “But those resources obviously are finite and things can change. So maybe this [proposed tax change] forces the legislature to become more nimble and to check how we’re spending.”

Some legislators, including Meyer, have contemplated complete elimination of the income tax. But he says the volatility of oil and gas tax revenue (which North Dakota relies on for its general fund as well as to build up reserves), combined with concerns about local property tax burdens, makes it prudent to keep the income tax as a revenue source.

Historic year for flat-tax supporters

All but seven U.S. states levy some kind of income tax (South Dakota is one of the exceptions), and most have some kind of tiered, “graduated” system — rates of taxation go up at higher income levels. But the Tax Foundation says the year 2022 marked “something of a flat tax revolution.”

“In more than a century of state income taxes, only four states have ever transitioned from a graduated-rate income tax to a flat tax,” Jared Walczak wrote for the foundation in September. “Another four adopted legislation doing so this year, and a planned transition in a fifth state (Arizona) is now going forward.”

In the Midwest, Illinois, Indiana and Michigan have had flat-tax systems since the 1960s (graduated-tax systems are barred in the Illinois and Michigan constitutions), and Iowa will soon join these states as the result of legislation passed this year.

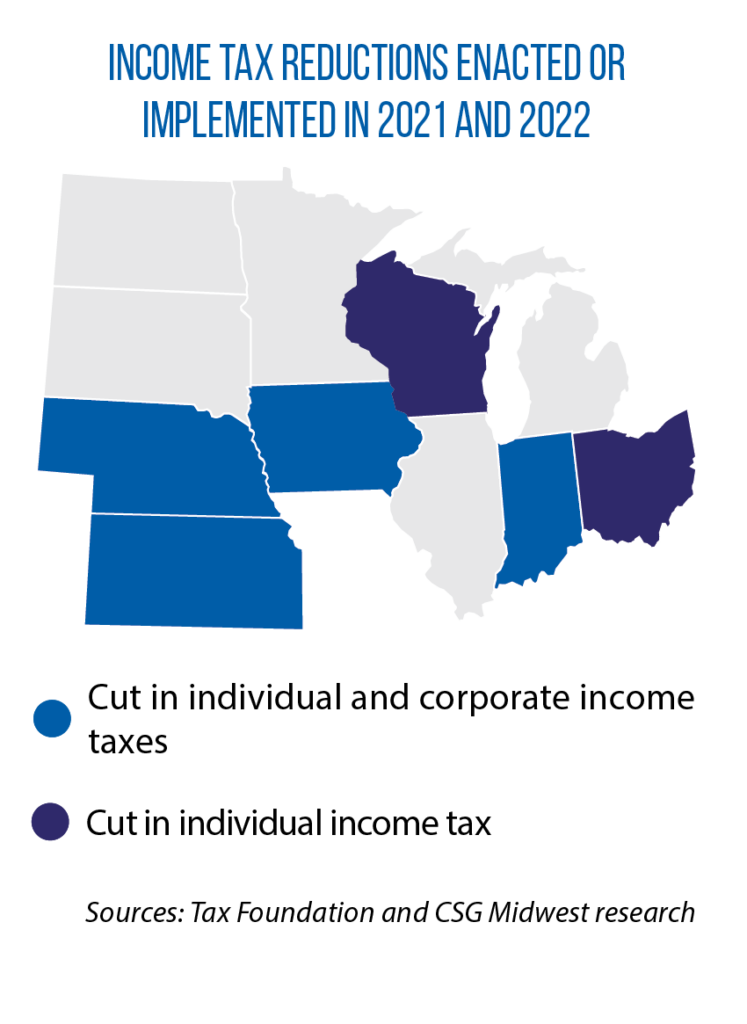

Under HF 2317, Iowa will gradually move to a flat tax rate of 3.9 percent by 2026. It has been one of seven Midwestern states with a graduated tax structure; for incomes above $78,435, the top rate is 8.53 percent. This transition to a flat tax in Iowa, along with a new exemption for retirement income, will reduce net general fund revenue by $1.2 billion in FY 2026, according to the state’s Legislative Services Agency. Additionally, if certain fiscal triggers are met, Iowa will transition to a flat corporate income rate of 5.5 percent.

Indiana and Nebraska also adopted income tax-related changes this year:

- Indiana’s HB 1002, signed into law in March, will drop the current flat rate of 3.23 percent to 3.15 percent starting next year. Further reductions will occur if two thresholds are met: 1) year-over-year revenue growth in the general fund is at least 2 percent, and 2) the balance in the state pension fund sufficiently covers pension liabilities. If these thresholds are met, the flax tax rate in Indiana falls to 2.9 percent by 2029. The revenue loss for the state would be an estimated $942 million by 2030, according to an analysis of HB 1002 by the Indiana Legislative Services Agency.

- In Nebraska, the top rate (which applies to incomes above $32,210 for single filers and $64,430 for joint filers) in the state’s graduated system will fall from 6.84 percent to 5.84 percent by 2027. LB 873, signed into law in April, also gradually drops the corporate income tax rate to 5.84 percent; accelerates a phaseout of Social Security income; and expands a refundable income tax program to not only include property taxes paid to K-12 schools, but community colleges as well. All told, by FY 2027-’28, the various provisions in LB 873 will result in a net revenue loss to the state of $948 million, Nebraska fiscal analysts say.

For Meyer, part of the appeal of the flat-tax proposal in North Dakota is that it’s simple and clean, and because of the exemptions from income taxation for many households, “everyone will benefit,” he says.

Supporters of a graduated system, in contrast, say it provides a counterweight to the regressivity of other major sources of state revenue such as the gas tax and sales tax.

“Higher rates on higher incomes are an effective way to capture the increasing share of economic benefits flowing to those at the very top,” Wesley Tharpe, deputy director of state policy research for the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, noted three years ago in an article supporting Illinois’ proposed switch from a flat tax to graduated income tax. (Illinois voters rejected this proposed constitutional change.)

Illinois expands reach of earned income tax credit

This year, the center tracked how some states used their strong fiscal standing to target relief for “families struggling to afford the basics.”

Illinois, for instance, permanently expanded its earned income tax credit (SB 157) from 18 percent to 20 percent of the federal credit while also making more people eligible — namely, childless adults between the ages of 18 and 24 or 65 and older, as well as certain immigrant workers.

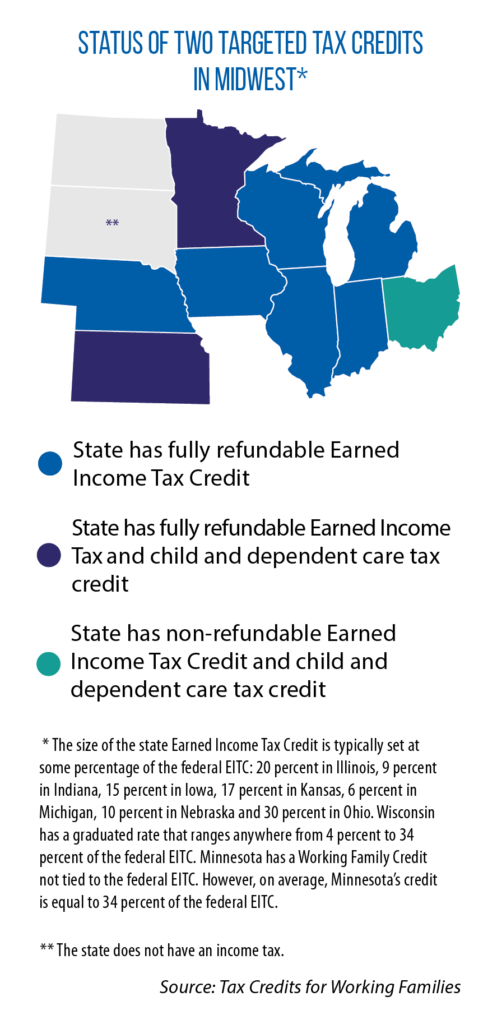

Most states in the Midwest have an EITC of some kind, but policies vary in terms of the amount of the credit and whether it is refundable or non-refundable. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, another policy option for states is to provide a child tax credit to families. Three U.S. states added such credits this year, but none in the Midwest.

Many states in the region do offer child care tax credits (see map). Other policy moves this year included an end to the grocery sales tax in Kansas (HB 2106) and the issuance of tax rebate/refund checks in states such as Illinois and Indiana.

Across the border in Saskatchewan, all tax filers are receiving a $500 tax credit as part of the province’s four-point “affordability plan.”