More electric vehicles on the road, more questions about road revenue

Options for replacing gas tax with other user-based models appear limited; Iowa has region’s first charging tax on electric vehicles while other states eye potential of per-mileage road fees

More electric vehicles on the road and more-efficient internal combustion engines are good developments for the environment, but they do pose a challenge for states.

How do we continue to fund roads at adequate levels, if a core part of transportation funding — revenue from the gas tax — erodes?

“It’s an issue that’s become more prevalent this year as people turned more to EVs last year,” says Brian Sigritz, director of state fiscal studies at the National Association of State Budget Officers.

“While it’s not dire, this is an accelerating issue, and states will have to deal with it.”

The fuel economy of vehicles on U.S. roads is at record highs and expected to rise further.

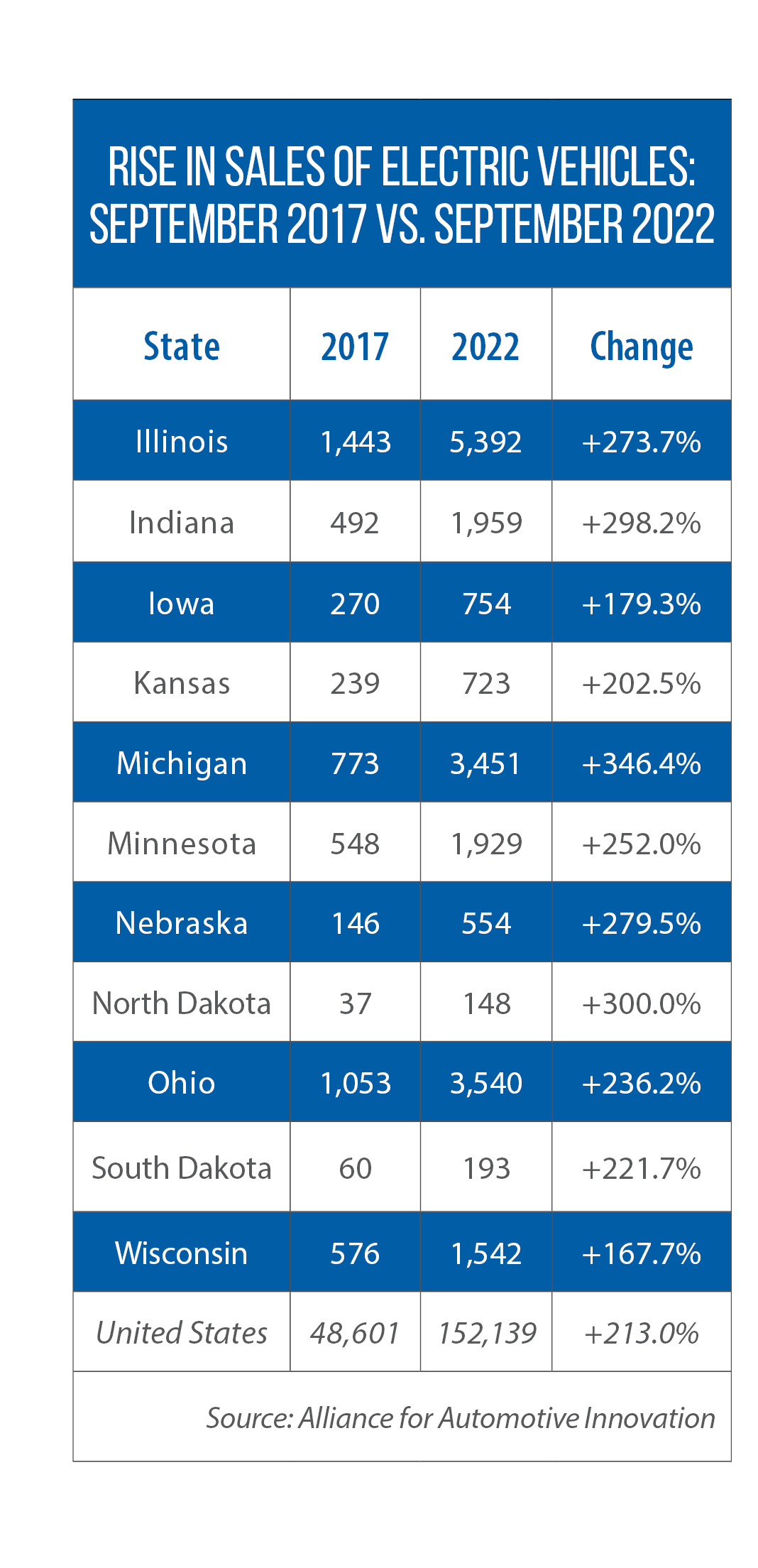

Meanwhile, between September 2017 and September 2022, EV sales nationwide rose by 213 percent. The increase was even steeper in most Midwestern states. And across the country, a mix of state and federal policies is incentivizing prospective car buyers to “go electric.”

In Illinois, the Clean Energy Jobs Act of 2021 (SB 2408) sets a goal of 1 million EV registrations in the state by 2030; that would be an increase of more than 900,000 compared to end-of-the-year totals from 2021.

In Illinois, the Clean Energy Jobs Act of 2021 (SB 2408) sets a goal of 1 million EV registrations in the state by 2030; that would be an increase of more than 900,000 compared to end-of-the-year totals from 2021.

User-based options for states are limited

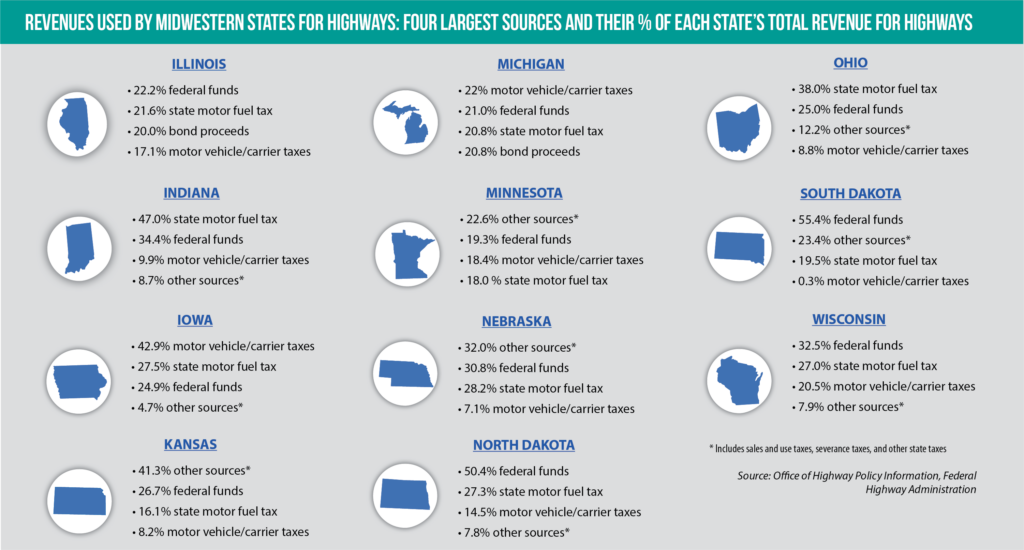

Traditionally, much of the financing of the nation’s highways, roads and bridges has come from a user-based revenue model: Charge motorists through registration fees, a motor fuel tax or other means.

The options for keeping this model intact, in an era when more motor vehicles require fewer or no trips to the gas pump, appear to be limited:

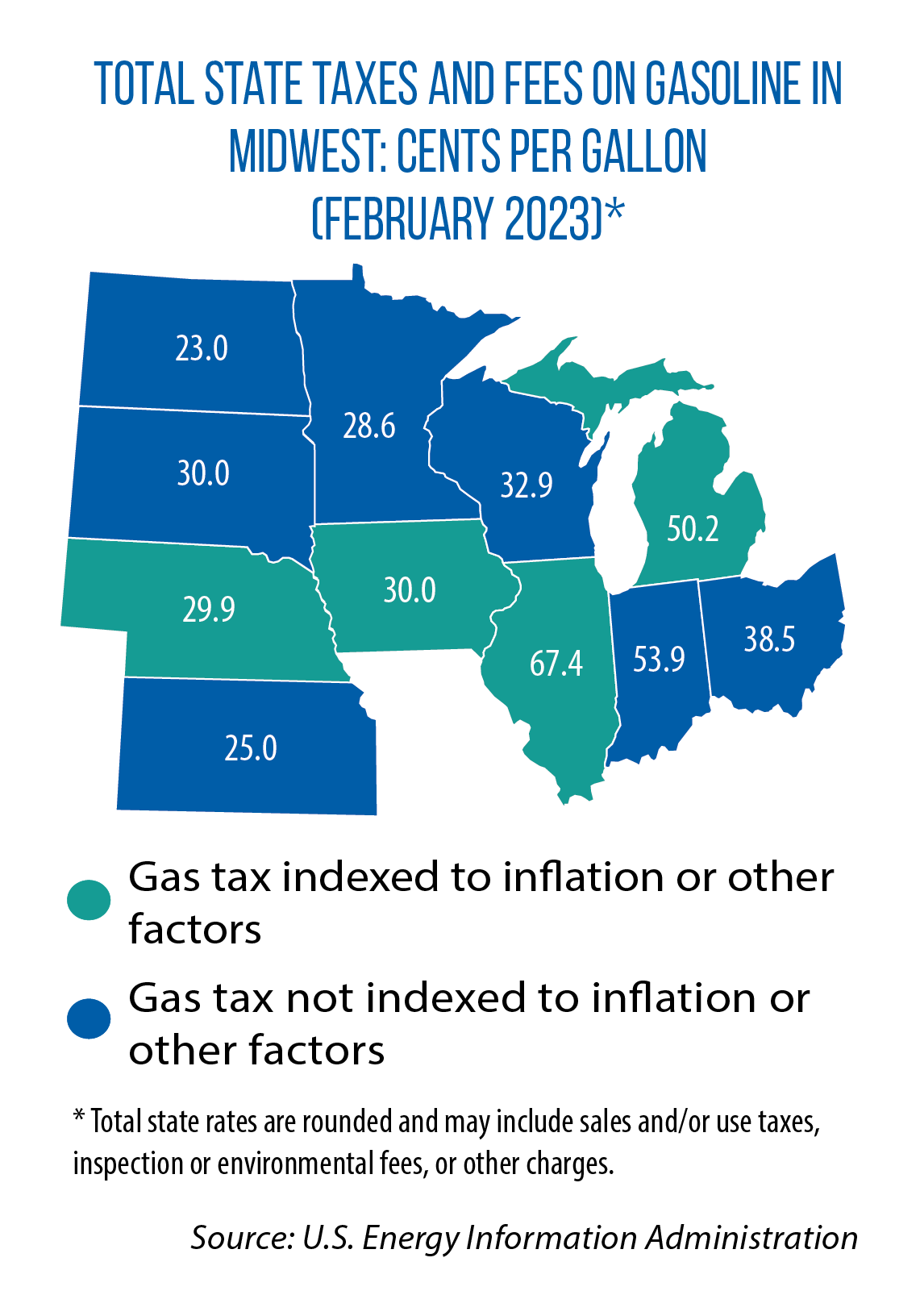

• Increase the motor fuel tax rate and/or index it to inflation.

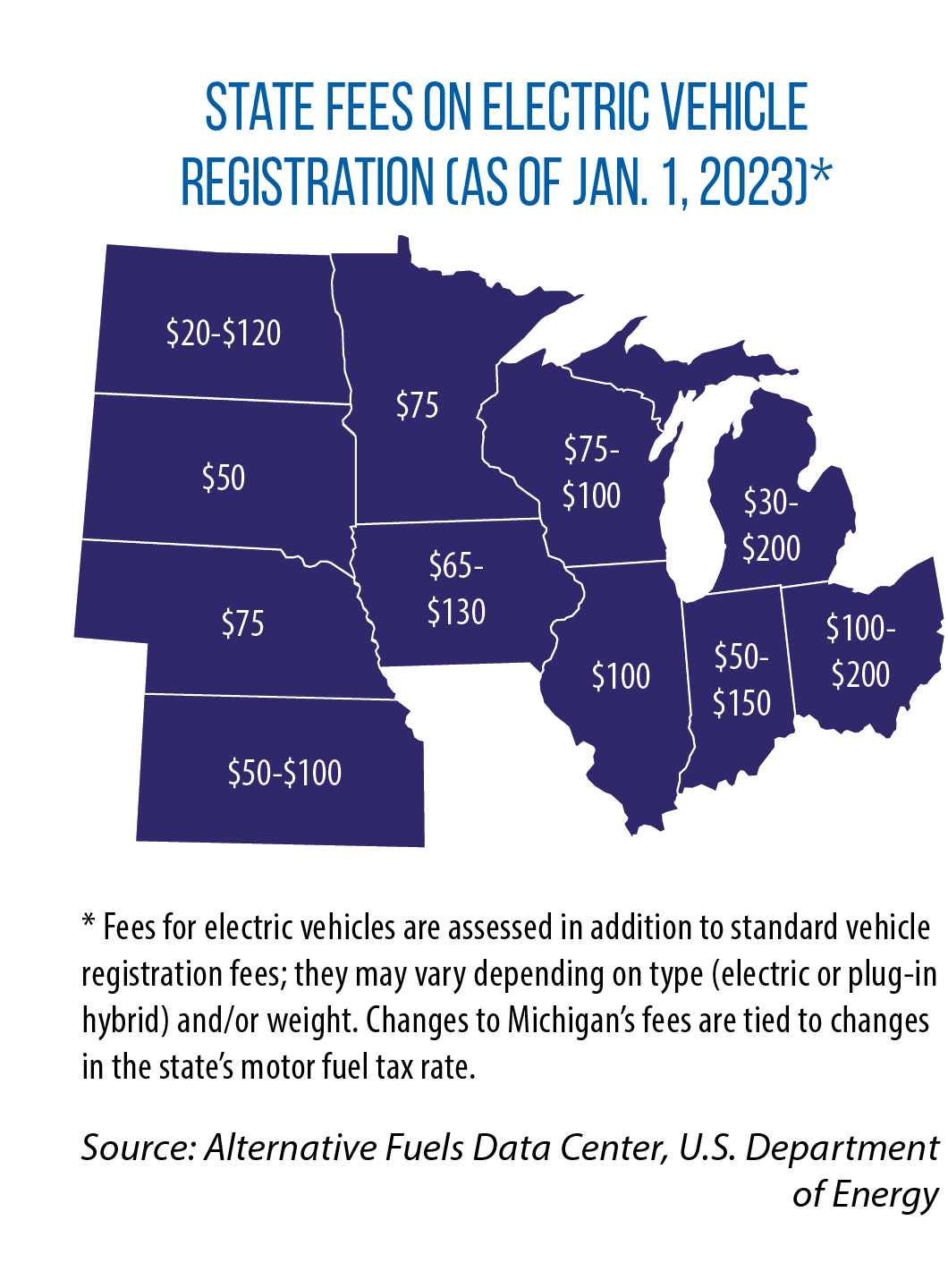

• Charge higher registration fees, particularly for electric vehicles.

• Begin the shift from fuel taxes to another kind of road-user fee — often called a mileage- or distance-based user fee, a road-use charge (RUC) or a vehicle-miles-traveled fee.

• Start taxing the electricity used to charge EVs as a fuel.

Two-thirds of all states have raised their motor fuel taxes since 2013, including all Midwestern states but Kansas, North Dakota and Wisconsin. Currently, only Illinois, Iowa, Michigan and Nebraska index the rates to inflation or other factors.

Thirty states, including all 11 in the Midwest, charge higher registration fees for electric vehicles, with the amount often varying based on vehicle type.

Multiple states and the federal government have been studying road-use charges for many years (decades, in some cases).

None, until recently, had implemented an EV charging tax.

Iowa will soon levy electric fuel excise tax

Starting July 1, Iowa will tax electricity used at all non-residential EV charging stations at the rate of 2.6 cents per kilowatt-hour (kWh) — the first Midwestern state to do so, and just the third nationwide after Kentucky and Pennsylvania.

Iowa’s EV charging tax is one facet of legislation passed four years ago, HF 767. That measure, in turn, was based on recommendations from a study that had been done one year earlier by the state Department of Transportation.

The goal of that legislatively mandated study: look at ways to prepare the state for long-term declines in motor fuel tax revenue. HF 767 also included a supplemental EV registration fee (beginning at $65 a year in 2020, now at $130) and created a hydrogen fuel excise tax of 65 cents per gallon equivalent — the amount of an alternative fuel needed to equal the energy of one gallon of gas.

According to Stuart Anderson, director of the Iowa DOT’s transportation development division, those three steps offered the best intermediate solution to the long-term decline in motor fuel tax revenue.

The DOT’s 2018 report said an EV charging tax “would be consistent with the existing process of collecting an excise tax on motor fuels” and, like taxes on traditional fuels, would function as a user fee that could be applied to out-of-state vehicles.

But the report also noted a problem: collecting this electric fuel excise tax from home-based chargers, where the U.S. Department of Energy estimates 80 percent of EV charging occurs, would be an administrative nightmare.

That’s one reason why the state of Oregon is focusing on a road-use charge, says Scott Boardman, a policy advisor in the Oregon Department of Transportation’s innovative programs office.

“Most charging is done at home, so it’s potentially very difficult to administer because you’d need a separate (electric) meter, or you’d have to ask people to report their usage honestly,” he notes.

Even so, the idea of an EV charging tax at public charging stations is generating legislative interest. Oklahoma will be the fourth state to implement the tax, starting in January 2024, under legislation (HB 2234) passed in 2021. Legislation from Kansas this year, HB 2004, calls for a 3-cent per kWh “road repair” tax on public EV chargers.

The bill’s sponsor, Rep. Bill Rhiley, says he proposed the tax to “solve the decline in road tax income and the increase in road and bridge repair costs.”

Kansas, Minnesota studying road-user charge

The fourth potential option for states is the road-user charge (RUC). It upholds the “user pays” principle and covers electric and internal combustion engine vehicles, says Owen Minott, a senior policy analyst at the Bipartisan Policy Center.

“A road-use charge is something you can start implementing and testing and beginning to adapt,” Minott says. “Whether or not it’s a perfect system, it’s the only available option for the medium term.”

Under voluntary RUC demonstration projects, states determine a per-mile charge. Mileage is tracked by “plug-ins” inserted into a vehicle’s on-board computer or smartphone apps. Some states also allow for manual data entry. Participating drivers are generally given a motor fuel tax credit for fuel purchases.

Kansas transportation officials are now studying the RUC concept, if only to get a Midwestern perspective into the national dialogue, says Joel Skelley, director of policy for the Kansas Department of Transportation, noting the nation’s coastal states often have been at the forefront on the issue.

The Kansas DOT’s “Midwest Road Use Charge” pilot program is scheduled to launch later this year. Once the demonstration phase is complete, Kansas will work with Minnesota to expand the study’s reach to interstate traffic, he says.

“We want a seat at the table, not to be on the menu,” Skelley adds. ‘We want to be proactive in looking at our options and not be pressured into picking something that’s not in our best interest.”

In its most recent study, Minnesota collected data on 64 vehicles that drove more than 565,000 miles. The DOT’s final report on the study, issued in August 2022, concluded that imposing a per-mileage fee is technically feasible.

But it also noted that several issues required “further analysis.” That includes evolving on-board vehicle technology, the logging of out-of-state travel and travel in Minnesota by out-of-state drivers, and how federal motor fuel tax credits would be administered.

Anderson says Iowa’s DOT is interested in the RUC concept and is keeping an eye on states’ pilot programs. But officials are not interested in an Iowa-only charge, which would forfeit fees from out-of-state vehicles, he adds.

“Our feeling was that [an RUC] needs to be driven at the national level rather than having 50 different solutions,” he says.

In 2013, Oregon legislators passed SB 810, creating OreGO, the first RUC pricing program in the nation. It is for light-duty vehicles with a fuel economy of 20 mpg or better.

Drivers opting in to the program pay 1.9 cents per mile and get a credit for the fuel tax (38 cents per gallon) they pay.

Participants choose from multiple options to track their mileage and pay the charge. GPS data may only be used to track miles, personal data can’t be disclosed, and all collected data is destroyed within 30 days of payment processing.

A legislative proposal in Oregon this year (HB 3297) would make the program mandatory beginning in July 2027 for model year 2028 vehicles getting 30 mpg or better.