Family losses of land and wealth are part of nation’s history; protecting future generations is among the goals of new laws on heirs’ property

Emily Dievendorf’s legislative district includes the urban center of Lansing as well as many acres of farmland surrounding Michigan’s capital city.

Among the issues the first-term lawmaker has found to unite her constituents, regardless of where they live, is an interest in helping families hold on to land as it passes from one generation to the next. That includes the preservation of family farms across her district and the state.

Among the issues the first-term lawmaker has found to unite her constituents, regardless of where they live, is an interest in helping families hold on to land as it passes from one generation to the next. That includes the preservation of family farms across her district and the state.

Earlier this year, Dievendorf introduced HB 4924, a bill that aims to improve the process of property transfers as well as provide new protections for heirs. “Many folks would be assumed to be on different sides of the political conversation and when it comes to this, they aren’t,” explains Dievendorf, “because we’re recognizing what happens over hundreds of years when you are not able to pass on the results of your work.”

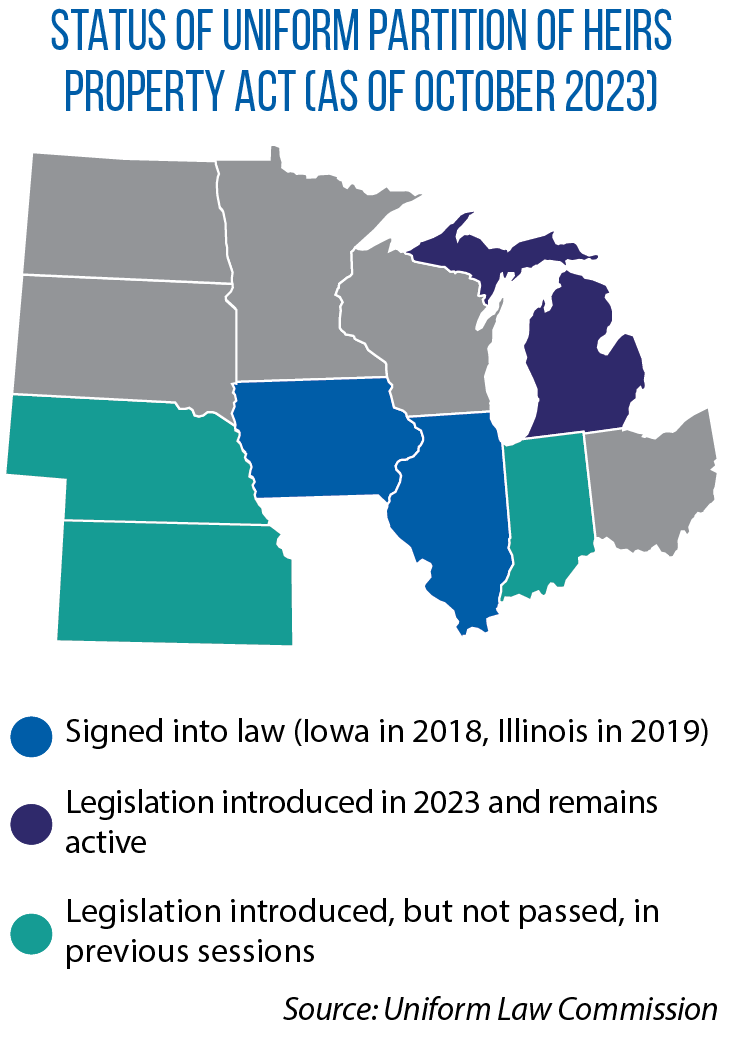

If HB 4924 becomes law, Michigan would join two other states in the Midwest, Iowa and Illinois, that have made similar statutory changes in recent years.

In all, 21 U.S. states as well as the District of Columbia and the U.S. Virgin Islands have adopted the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act (or measures “substantially similar”) since the nonpartisan Uniform Law Commission drafted the model legislation in 2010.

In all, 21 U.S. states as well as the District of Columbia and the U.S. Virgin Islands have adopted the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act (or measures “substantially similar”) since the nonpartisan Uniform Law Commission drafted the model legislation in 2010.

What is heirs’ property?

When a landowner dies without a will, the land passes to his or her heirs according to state law. When there are multiple heirs, they all become owners of an undivided interest in land as “tenants-in-common.”

After several generations of land being passed without a will, it is possible (and common) for land to be owned by many individuals. In some instances, there may be as many as 80 owners of a single tract of land.

Unanimous decision-making on the property is required by the tenants-in-common. Additionally, each tenant-in-common has the right to seek partition from the court in one of two ways:

1) request the physical division of the land into smaller parcels, known as partition-in-kind; or, if that is not possible,

2) partition by a court-ordered sale.

When the Uniform Law Commission drafted the legislation, it described flaws within the current system this way:

“Tenants-in-common are vulnerable because any individual tenant can force a partition. Too often, real estate speculators acquire a small share of heirs’ property in order to file a partition action and force a sale. Using this tactic, an investor can acquire the entire parcel for a price well below its fair market value and deplete a family’s inherited wealth in the process.”

The Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act aims to preserve generational land wealth — whether that land is a city lot or a family farm.

“[The act] doesn’t change a state’s inheritance laws, it changes the processes,” says Rusty Rumley, an attorney with the National Agricultural Law Center.

For example, it requires notice, a court-ordered independent appraisal of the property’s value, and a right of first refusal, thus allowing co-tenants to buy out the party seeking partition. Perhaps most importantly, Rumley says, the act requires an open-market commercial sale rather than auction if the co-tenants cannot come to an agreement.

Traditionally, court-ordered sales are completed via an auction. Often, though, the only bidders are the speculators or investors who initially requested the partition; as a result, they have been able to purchase the land for less than the market value.

Complications for farmland heirs

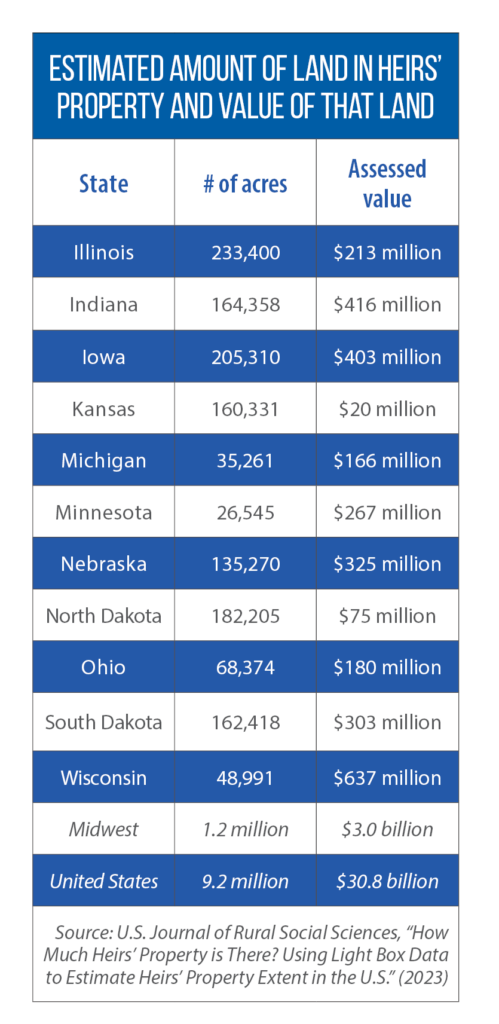

Across the Midwest, an estimated 1.2 million acres of land is being held as heirs’ property, according to a 2023 study in the U.S. Journal of Rural Social Sciences. The assessed value of that land is estimated at a little more than $3 billion.

Across the Midwest, an estimated 1.2 million acres of land is being held as heirs’ property, according to a 2023 study in the U.S. Journal of Rural Social Sciences. The assessed value of that land is estimated at a little more than $3 billion.

These numbers could rise as more property, particularly farmland, gets transferred to the next generation. (More than one-third of the nation’s are age 65 or older.) While most farmers have estate plans, a significant number of them do not. Even if there is a plan, complications can lead to land being classified as heirs’ property.

“Any language (whether in a formal estate plan or following the laws of intestacy) that creates a tenancy-in-common ends up as heirs’ property unless those heirs do something proactively to address the issue,” Rumley explains, “such as buying other siblings out or putting the property in a trust.”

Farming land held as heirs’ property is difficult.

Lending agencies will not use heirs’ property as collateral for purposes of issuing financing because the title is considered “clouded.” Without such financing options, investments in farm operations, such as purchasing new land or more equipment, may not be feasible.

Additionally, until passage of the 2018 farm bill, there had been no way for heirs’ property owners to get a farm number, which is necessary to secure federal crop insurance and lending.

That 2018 update was critical, Rep. Dievendorf says. Now, heirs’ property owners can get a farm number, and it is easier if they farm in a state that has adopted the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act. It’s one of the reasons Dievendorf is pushing for the passage of HB 4924 in Michigan.

Still, complications remain for heirs. As a result, those who want to farm may be pushed out of the industry, forced to sell, or rent the land rather than farm it themselves.

‘For future generations’

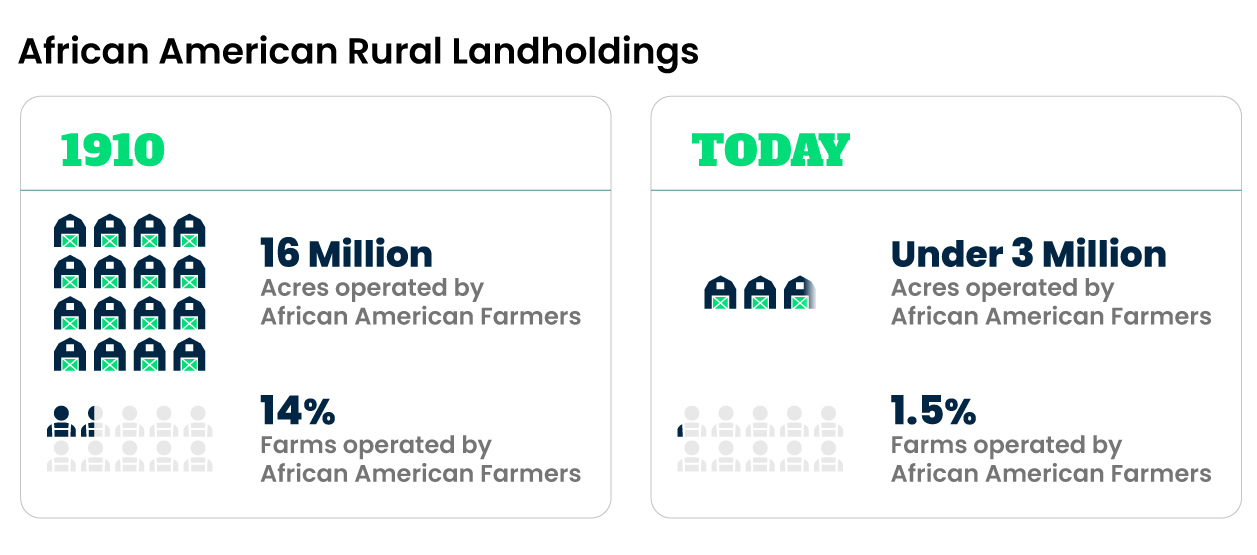

Of all the reasons for introducing the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act, Dievendorf says, the most compelling to her was the nation’s history of stripping property from generations of Black and Indigenous Americans, partly through the use of inheritance laws.

Graphic from the Center for Agriculture & Food Systems

Between the end of slavery and 1910, African American farmers acquired 16 million acres of land. Over the next 100 years, their land ownership fell to less than 3 million acres. David Dietrich, as co-chair of the American Bar Association’s Property Preservation Task Force, described the ramifications of heirs’ property law as “the worst problem you never heard of.”

Mavis Gragg, a leading expert on heirs’ property, explains that for many years, African American farmers “intentionally would pass ownership through intestate succession” and “forgo having wills that you have to file with the county clerk.” That’s because it was safer if ownership was obscured.

Heirs’ property has impacted Indigenous land ownership as well.

The 1887 Dawes Act permitted the allotment of Native American reservations. Individual members were allowed to own individual parcels, but they were subject to state inheritance laws. Because Native Americans were not legally permitted to use wills to transfer land until 1910, a significant amount of these allotments became heirs’ property.

Fast-forward to today, and legislators such as Dievendorf are looking for a way to ensure future generations don’t unfairly lose their land or wealth.

“[I]t closes a loophole that absolutely should not have existed,” says Dievendorf, adding that by making a change in the law, a state can show “that property equity is not just for the present generation, but for future generations.”