Should deception be allowed in police interrogation of juveniles? The question is being raised in legislatures; two Midwest states ban the practice

Some states in the Midwest, and across the country, are re-evaluating whether law enforcement officials should be allowed to purposely present false information to detained minors during an interrogation in order to, for example, solicit a “confession.”

“ ‘Don’t lie to children’ is a powerful message,’ ” says Steven Drizin, a clinical professor of law at Northwestern University and co-director of the Center on Wrongful Convictions. “Children, even more so than adults, are deferential to authority figures. And that is especially so in the interrogation room.”

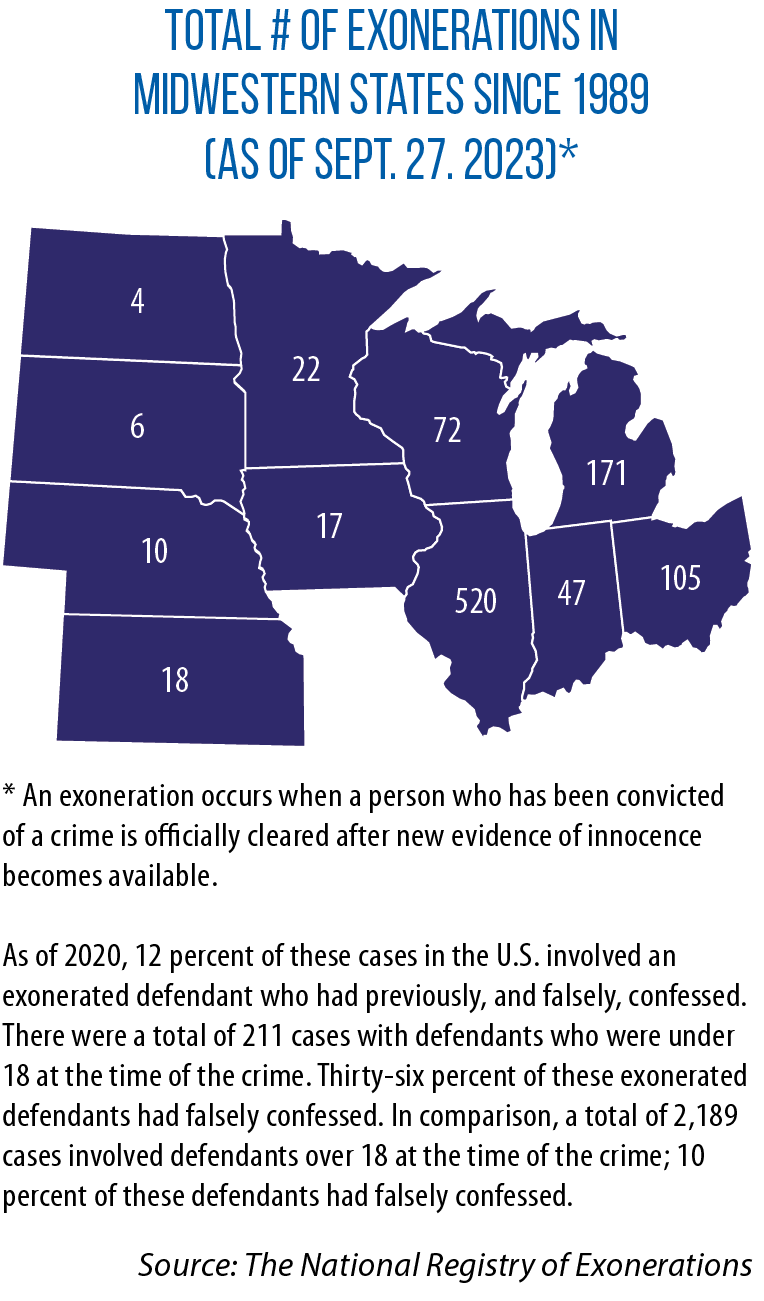

According to the Innocence Project, among cases that ended in exoneration between 1989 and 2020 due to DNA testing, 29 percent involved a false confession. Thirty-one percent of the false confessors were 18 years old or younger at the time of arrest.

“Deceptive interrogation tactics lead to false confessions and injustice for both the persons who falsely confess as well as the victims of the crime because the true assailant is not brought to justice,” Nebraska Sen. John Cavanaugh says.

“Deceptive interrogation tactics lead to false confessions and injustice for both the persons who falsely confess as well as the victims of the crime because the true assailant is not brought to justice,” Nebraska Sen. John Cavanaugh says.

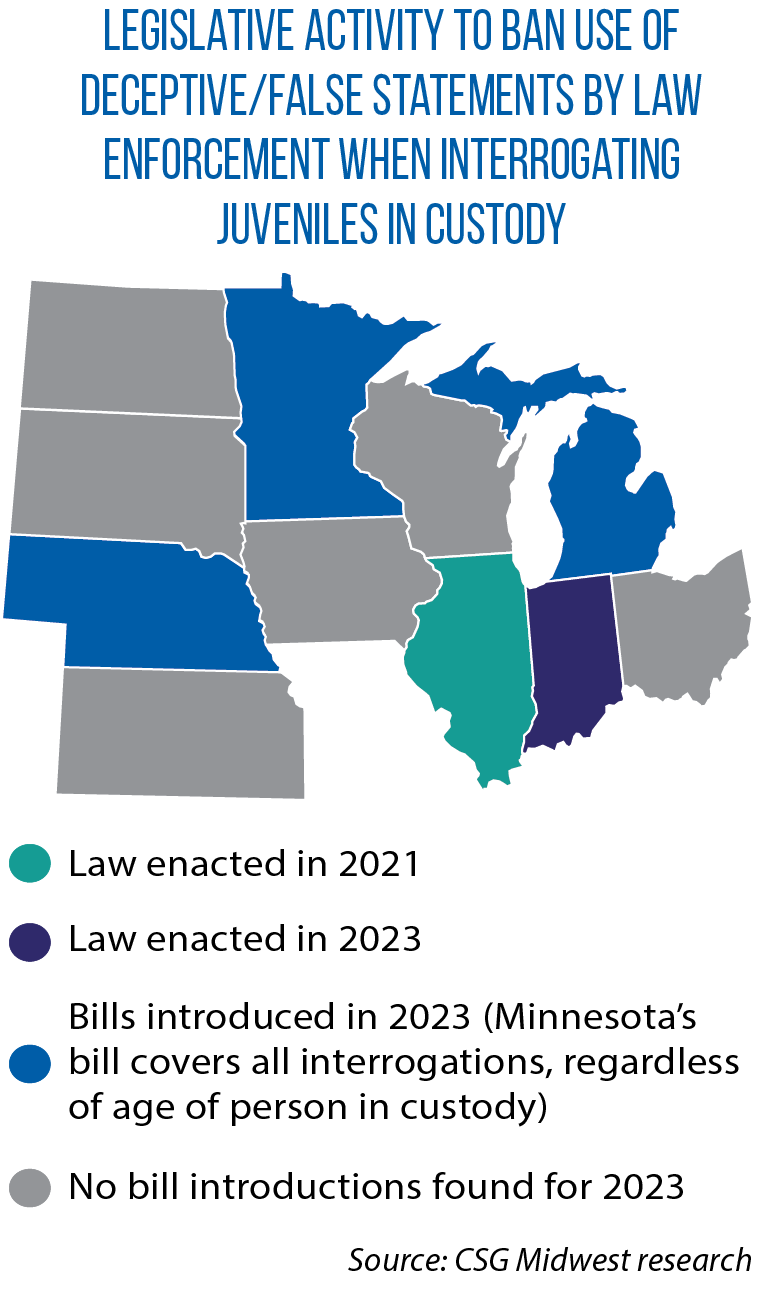

He sponsored LB 135 in 2023, a year in which “anti-deception” measures were introduced in Nebraska and three other Midwestern legislatures (see map).

Indiana: No false facts, notify parent/guardian

Passed unanimously by the Indiana General Assembly, SB 415 includes two main provisions involving the interrogation of juveniles.

First, it aims to stop law enforcement and school resource officers from knowingly offering false facts about evidence or making false statements about possible leniency to detained individuals younger than 18 years old. Statements, including confessions, made by a young person under these circumstances are now inadmissible in criminal or juvenile proceedings against the person.

Second, SB 415 requires law enforcement to make a “reasonable attempt” to notify a child’s parent, guardian or emergency contact when the young person has been arrested or taken into custody for a crime committed at a school or at a school-sponsored activity.

There are certain exceptions to this second requirement — for example, if the juvenile is emancipated, or if a medical emergency or student safety are involved.

“I don’t believe that law enforcement frequently engages in providing false information to children,” Sen. Rodney Pol said following the passage of his bill. “Yet any time it does happen, [it’s] harmful to children, their future, their families, and the justice system. … This bill seeks to stop those confessions and build more trust.”

At least two other like-minded bills were introduced this year in Midwestern legislatures: Michigan’s HB 4436 and Nebraska’s LB 135. Cavanaugh says his measure remains alive for the 2024 session. In Minnesota, HF 2319/SF 2495 would have made admissions, confessions or statements inadmissible in all instances where law enforcement uses deceptive tactics — no matter the age of the person being interrogated.

In all three states, these bills did not advance out of committee in 2023.

Illinois: No confessions via ‘knowing deception’

According to Drizin, Indiana joined eight other U.S. states that have changed their laws in recent years to prevent intentionally deceptive tactics by law enforcement when interrogating minors. The first state to pass such a law was Illinois. The final version of SB 2122, signed into law in 2021, received unanimous approval in the House and Senate.

Under the law, a confession by a juvenile, whether oral or written, is inadmissible in a criminal proceeding in most circumstances if it was “procured through the knowing use of deception.”

“This is not only a criminal justice reform bill that has bipartisan sponsorship support but, equally important, has strong support from our law enforcement partners,” Rep. Justin Slaughter, the bill’s chief sponsor, said on the House floor as SB 2122 moved through the Illinois General Assembly.

“As it relates to prosecutors proving the voluntariness of confessions, we lowered the burden-of-proof standard to make that easier for them.

“Secondly, we limited what qualifies as an inadmissible statement. We wanted to clarify that a statement made by the minor that incriminates someone else would still be admissible, even if deception was used.”

“Secondly, we limited what qualifies as an inadmissible statement. We wanted to clarify that a statement made by the minor that incriminates someone else would still be admissible, even if deception was used.”

At the time, Illinois Rep. Curtis Tarver said these new protections for young people should also be extended to adults with limited cognitive abilities, arguing that this population is just as vulnerable to deceptive coercion.

“I don’t know that a 35-year-old who is essentially functioning with a mindset of a 14-year-old should have deception used on him or her in any manner that’s different because they’re not 18 or under,” he said.

Two years later, Tarver’s HB 3253 was signed into law. It takes effect in 2024 and bars the use of deceptive tactics in interrogations of individuals of any age with a “severe or profound intellectual disability.”

Miranda rights: Clear language for children

Along with these anti-deception measures, Drizin says clearer explanations to young people of their Miranda rights can help avoid miscommunication with law enforcement. Children and adolescents have a harder time than adults in understanding and exercising these rights than adults, he adds, especially under stressful conditions.

“Making the language of the rights more simple and understandable [could help], or requiring that children explain back to law enforcement officers what they understand after they’re given their rights,” he says.

In states such as Maryland, California, and Washington, Drizin notes, a consultation with an attorney is required before minors can waive their Miranda rights.

In 2016, Illinois (SB 2370) began requiring that an attorney be present for an interrogation of individuals 15 and younger in murder or sex-offense cases, that interrogations of juveniles be videotaped, and that officers use a simpler version of the Miranda warning in interactions with young people.

Officers must now say this to young people: “You have the right to get help from a lawyer; if you cannot pay for a lawyer, the court will get you one for free.”

They must then ask the juvenile two questions: “Do you want to have a lawyer?” and “Do you want to talk to me?”

Without the use of this language, statements made by the juvenile become inadmissible.

EXAMPLES OF STATE LAWS TO PROTECT YOUNG PEOPLE DURING INTERACTIONS WITH POLICE

Prohibit confessions or admissions from being used against a child under a certain age

Prohibit confessions or admissions from being used against a child under a certain age- Establish a right for minors, which cannot be waived, to consult with legal counsel prior to interrogation

- Require interrogations to be electronically or video recorded

- Bar law enforcement from knowingly using deception

- Require the presence of a parent/guardian or attorney

- Require the use of Miranda warnings that help children better understand their rights