Midwest’s legislatures explore paths to property tax relief

The property tax, Joan Youngman says, “will never have a quiet life.”

On the one hand, people are reminded every day of the critical amenities provided through this local revenue source — schools, roads, police, etc. “Voters are aware of their property values and of the services, and that’s a good thing for [local] accountability and responsible decision making,” says Youngman, a senior fellow and chair of the Department of Valuation and Taxation at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

On the other hand, they also are mindful of the costs.

How much did you pay last year in property taxes? People are much more likely to know that answer compared to sales or income taxes, at least in part because the property tax typically is collected as a lump-sum payment and can total thousands of dollars.

How much did you pay last year in property taxes? People are much more likely to know that answer compared to sales or income taxes, at least in part because the property tax typically is collected as a lump-sum payment and can total thousands of dollars.

In recent years, Rep. Mike Amyx says, he and other Kansas lawmakers have been hearing loud and clear from constituents about the impacts of rising property taxes.

“The values of properties are going up; people’s incomes have not [kept pace]. And, of course, you have folks on fixed income,” he says. “We’re seeing some fairly big hardships because of that.”

In his State of the State address in January, Nebraska Gov. Jim Pillen identified “out-of-control property taxes” as the state’s “most important economic issue.” His goal: sign new laws this session that result in a 40 percent reduction in property taxes. Kansas and Nebraska are not alone. Youngman notes that in just about every state where legislatures are in session, bills have been filed to provide some kind of relief.

Rising vales, rising taxes

U.S. home values reached an average of $342,941 in January 2024, according to the Zillow Home Value Index; that is an increase of 68.3 percent since January 2017. The annual growth in home values was 3.1 percent between January 2023 and January 2024.

The value of agricultural land has been on the rise as well. Last year alone, it went up 7.4 percent. Between 2009 and 2023, the value of farmland nearly doubled, from $2,090 per acre, on average, to $4,080, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

This kind of jump in property valuations often results in higher tax bills, putting more pressure on lawmakers to intervene.

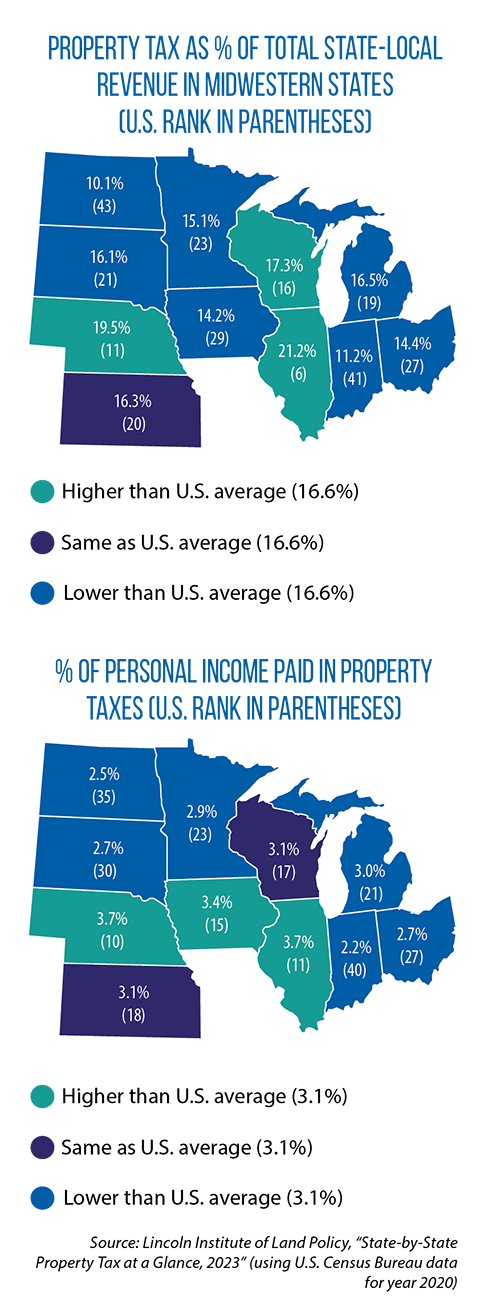

Most states in the Midwest fall somewhere in the middle of U.S. states on measures of property tax burdens and reliance (see maps), but there are exceptions.

Indiana, for instance, ranks in the bottom one-fifth of states.

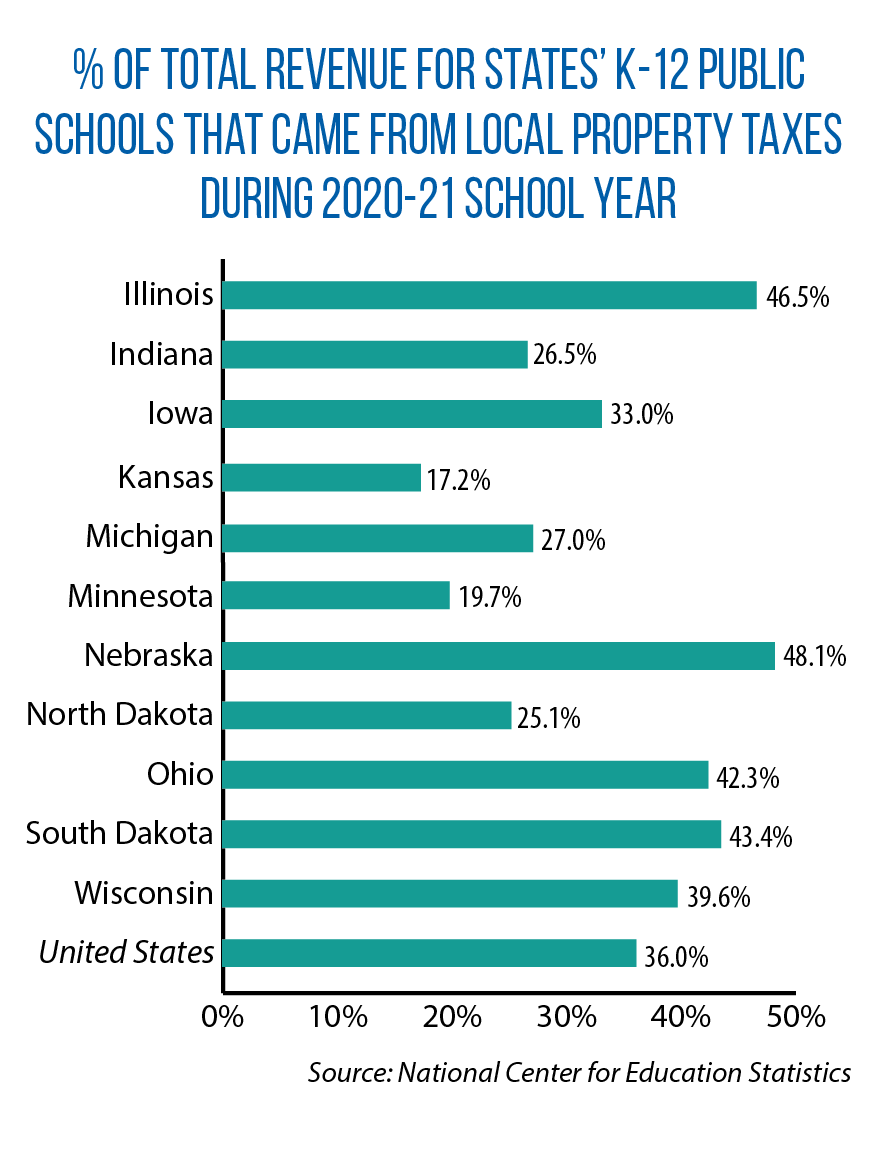

Statutory changes made there a decade-and-a-half ago allowed for a “tax swap” that reduced reliance on the property tax. The General Assembly raised the sales tax rate from 6 percent to 7 percent and had the state assume full funding responsibility for the costs associated with day-to-day student instruction in K-12 schools. Around the same time, a legislative-initiated, voter-approved constitutional amendment established new property tax caps. For instance, the tax paid by an Indiana homeowner cannot exceed 1 percent of the property’s gross assessed value.

On the flip side, Nebraska is one of the Midwestern states (along with Illinois) with a higher-than-average reliance on the property tax.

Numerous legislative proposals this year would change that and add new revenue sources in exchange for the 40 percent reduction in property taxes envisioned by Gov. Pillen. For example:

- Raise Nebraska’s sales tax rate from 5.5 percent to 6.5 percent.

- Broaden the sales tax base by imposing a tax on more services (for example, dry cleaning, digital advertising, accounting, storage and moving, and business legal services), on candy and soda, on lottery tickets and games of skill, and on certain agricultural-equipment parts.

- Raise the cigarette tax by $2 a pack (from 64 cents to $2.64).

Nebraska Sen. Lou Ann Linehan says a series of legislative changes are needed to bring a more balanced approach to government finance. She and others refer to it as the “three-legged stool”: income, sales and property taxes accounting for roughly the same amount of revenue for state and local governments.

The stool is no longer level, Linehan says, with property tax collections in Nebraska now at $5 billion, compared to $3 billion in income taxes and $2 billion in sales taxes.

She adds that additional revenue sources from sales and other taxes should only be part of the solution. Linehan also wants harder, state-level caps that limit annual growth in tax collections by local governments; under her proposed LB 1414, the total amount being collected would mostly have to remain the same from one year to the next. (There are exceptions to account for new construction or to pay off bonds, and allow voters to approve higher amounts.)

She adds that additional revenue sources from sales and other taxes should only be part of the solution. Linehan also wants harder, state-level caps that limit annual growth in tax collections by local governments; under her proposed LB 1414, the total amount being collected would mostly have to remain the same from one year to the next. (There are exceptions to account for new construction or to pay off bonds, and allow voters to approve higher amounts.)

This harder cap, Linehan says, will keep property taxes in check even as property values rise. LB 1414 does not apply to school districts, though a measure passed last year (LB 243) curbs districts’ year-over-year increases to 3 percent, with exceptions to account for growth in overall enrollment or the number of higher-need students.

Outside the Legislature, advocates of eliminating all income, property and inheritance taxes in Nebraska are seeking to get their proposal on the November 2024 ballot. Their idea is to fund state and local government through a consumption tax. A petition to end property taxes in North Dakota, via a constitutional amendment, also has been circulating.

Transparency in taxation

In Kansas, any proposed constitutional amendments must first get legislative approval, and Democrats and Republicans have proposed separate property tax-related measures. The Republican plan would limit counties from raising the valuation on any property by more than 4 percent in a single year; the Democratic proposal would reduce the rate at which residential property is assessed, from 11.5 percent to 9 percent. (Rates are set in the Constitution.)

Statutory-level changes also are under consideration this session. One idea is to expand Kansas’ existing homestead exemption, a policy lever common across the country.

According to Youngman, homestead exemptions tend to be politically popular because they often cover all owner-occupied homes, providing broad relief to property owners. In contrast, “circuit breaker” programs are typically more targeted and provide assistance only once property taxes exceed a certain percentage of a homeowner’s income. (Some state-designed exemptions, Youngman notes, are targeted to seniors, veterans or other certain groups of homeowners.)

If set as a fixed-dollar amount (rather than a percentage of the home’s worth), the homestead exemption can help counter-balance “the inherent regressivity in tax valuations,” says Youngman, noting that “the lower end of the residential class tends to be over-assessed.”

She suggests that state legislatures fund these exemptions, rather than leaving it to local governments to find ways of making up the lost revenue.

Proposals in Kansas would raise the homestead exemption on the statewide property tax to $100,000 of valuation; it already was raised two years ago from $20,000 to $40,000 under HB 2239.

Homestead exemptions, circuit breaker programs, assessment and levy limits, and property tax rate caps are among the ways that states in the Midwest have sought to curb property taxes. But Youngman also says there is value in increasing state-level transparency, while retaining local autonomy over budgeting decisions that impact local services.

In Kansas, a “truth in taxation” law passed in 2021 (SB 13) now requires local taxing bodies to alert residents and hold public hearings prior to any vote that increases property tax collections.

“It’s an inhibiting step [to increasing taxes] because you no longer can have what you might call a ‘silent tax increase,’ ” says Youngman, noting that property tax collections can rise simply because of rising assessment values. “At the same time, you’re not imposing [limits] from a higher level of government. You’re not requiring a one-size-fits-all approach when areas of the state may have very different needs and resources.”

She also recommends stronger state oversight of locally administered property tax systems to ensure accuracy, fairness and accountability. Options for that oversight could be a legislative committee or a state-level board or official.

Paths to property tax relief: An overview of state policy strategies and examples from the 11-state Midwest

- Provide homestead exemptions that reduce the taxable value of a property owner’s primary residence. The exemption is typically a fixed-dollar amount set in statute. Two years ago, Kansas legislators raised the exemption on the statewide property tax from $20,000 of valuation to $40,000; HB 2239 also included a trigger that automatically increases the exemption to coincide with statewide rises in property values. Various proposals in the 2024 session would raise the exemption to $100,000.

Establish assessment limits that cap how much a property’s value (for tax purposes) can increase from year to year. Under the Michigan Constitution, the taxable value of property cannot grow by more than 5 percent or the rate of inflation (whichever is less) until ownership is transferred.

Establish assessment limits that cap how much a property’s value (for tax purposes) can increase from year to year. Under the Michigan Constitution, the taxable value of property cannot grow by more than 5 percent or the rate of inflation (whichever is less) until ownership is transferred.- Impose a tax rate cap that is tied to the value of the property. Constitutional language in Indiana guarantees that the tax paid by individuals on their primary residence will not exceed 1 percent of the property’s gross assessed value. The cap is 2 percent for residential non-homesteads and 3 percent for other property.

- Institute levy limits that curb how much revenue can be collected by local governments, with year-over-year growth typically capped at a certain percentage. Iowa legislators established new tiered levy limits last year. Under HF 718, when overall property assessments in a taxing district rise between 3 percent and 6 percent, the levy limit is set at 2 percent. When assessments increase 6 percent or more, levy growth is capped at 3 percent.

- Increase general aid to local governments. This was among several property tax relief provisions included in Minnesota’s omnibus tax bill from 2023. HF 1938 included an additional $80 million each year in local government aid and county program aid. With this influx of state dollars, lawmakers say, local governments can deliver critical services and avoid property tax increases.

- Raise state-based taxes. The property tax limits and caps in Indiana and Michigan (see above) were implemented at the same time those states raised sales tax rates. One goal of these “tax swaps” was to reduce a reliance on the property tax to fund K-12 schools.

- Offer targeted relief when the property tax bill for a homeowner exceeds a certain percentage of income. Minnesota has one of the nation’s furthest-reaching circuit breaker programs: a high maximum refund (compared to many states), with eligibility open to all income-qualifying homeowners and renters. In other states, eligibility may be limited to seniors or the disabled and not include renters.

- Provide income tax credits to homeowners and other property-tax payers. In Wisconsin, a school levy tax credit is applied to every taxable property. Recent laws in Nebraska made property owners eligible for a refundable income tax credit based on the amount they pay in property taxes to the local school district and community college.

- Allow for the postponed payment of taxes until the property is sold or the owner dies. Illinois is among the states with this kind of property tax deferral program, and a 2021 law (SB 2244) expanded eligibility for it. Illinois seniors with incomes of up to $65,000 now qualify. The maximum amount that can be deferred every year also was raised to $7,500.

- Adopt “truth-in-taxation” laws. One example of this approach is Kansas’ SB 13, a law passed in 2021 that requires a local taxing body to alert residents and hold a public hearing prior to any vote that increases the amount of total property tax revenue it collects. This requirement includes sending a notice to each property-tax payer about the proposed increase and the public hearing. A similar law was enacted in Nebraska in 2021 (LB 644).