Taking the ‘middle pathway’

Iowa, Michigan laws reflect rising demand for workers with postsecondary training, but not necessarily bachelor’s degrees

Ambitious plans with ambitious goals: That describes how policymakers in two Midwestern states approached efforts in 2018 to ensure that their respective workforces can meet the demands of employers in an increasingly technological, skill-based economy.

In Michigan, lawmakers enacted Gov. Rick Snyder’s Marshall Plan for Talent (SB 941 and SB 942), which will invest $100 million to rebuild the state’s workforce pipeline. In Iowa, Gov. Kim Reynolds continues to champion a statewide goal first set when she was lieutenant governor: Increase the share of workers with a postsecondary education, training or credentials to 70 percent by 2025. (Currently, 58 percent of Iowans have education or training beyond a high school degree.)

These policy shifts in states such as Michigan and Iowa are a response to long-term changes in the U.S. economy.

According to Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce, in 1973, only 28 percent of U.S. jobs required education beyond high school. By 2025, the center says, two-thirds of jobs will demand some postsecondary education or training.

“We’re finding that in manufacturing, in particular, and other industries, there is upskilling going on,” says Neil Ridley, the center’s director of state initiatives. “Workers who in the past could do fairly well with just a high school diploma or less are increasingly being hired with a technical associate’s degree or certification that shows the acquisition of a skill.”

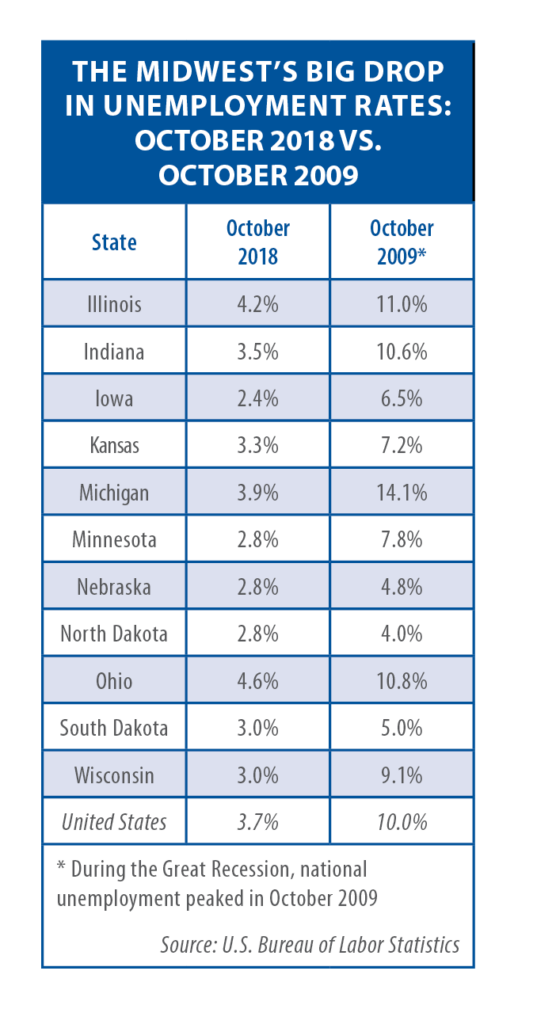

According to the National Skills Coalition, these “middle skill” jobs, which require education beyond high school but not a four-year degree, make up the largest part of the U.S. labor market. Today, especially with unemployment rates low in many states (see table), the supply of these workers is not keeping up with demand.

Michigan’s $100 million plan

Over the past decade, few states have seen a greater shift in the labor market than Michigan. During the Great Recession, that state’s unemployment rate hit a high of 14.6 percent, highest in the nation.

Since then, though, Michigan has experienced a period of economic growth; the state now has a jobless rate of 3.9 percent, only slightly higher than the national average and lower than its industrial counterparts of Ohio and Illinois.

This trend has created tight labor markets in which employers cannot find skilled workers to fill job openings.

According to Michigan’s Department of Talent and Economic Development, 100,000 workers are needed to fill high-wage, high-demand positions in the state. That number is projected to grow to 811,000 by 2024. Those projected job openings carry with them $50 billion in potential payroll earnings.

“From welders to nurses to software engineers and mechanical engineers, in all of these industries we’ll see some kind of shortage,” says Michigan Sen. Ken Horn, chair of the Senate Economic Development and International Investment Committee. “That is where we have to focus when we start thinking about making investments into finding this talent.”

The state’s new Marshall Plan for Talent appropriates $100 million for a talent investment fund to improve worker skills. Nearly $59 million is set aside for schools to improve their education and training programs — for example, competency-based learning programs related to high-demand, high-wage careers; improvements in vocational and career education; and new school-business partnerships.

Michigan school districts applying for these competitive state grants are required to create talent consortiums — collaborations between educators and employers that change the way students are prepared for careers. (See the sidebar article below for more details on the Marshall Plan for Talent.)

Encouraging these types of partnerships, Ridley says, is a valuable part of any state’s overall plan to improve the school-to-workforce pipeline: “[They] are critical for breaking down some of the disconnects that sometimes occur between educators and businesses and employers.”

Iowa’s investment in Future Ready

Iowa’s big policy response in 2018 came in April with the Legislature’s passage of HF 2458, known as the Future Ready Iowa Act.

“We have a bit of a mismatch in the types of jobs that are available and the education that our kids, and even our adults, are getting,” says Iowa Rep. Brian Best, chair of the House Economic Development Appropriations Subcommittee. “There are a lot of jobs available, but the skills aren’t there to fill them.”

Future Ready Iowa includes:

- an apprenticeship-development program for small and medium-sized businesses;

- a volunteer mentoring program and a summer youth intern program for at-risk students;

- last-dollar scholarships to increase the number of workers with associate’s degrees in high-demand fields;

- grants to help students complete bachelor’s degrees in high-demand fields; and

- an employer innovation fund that will expand credit and non-credit learning opportunities for people to pursue high-demand careers.

The new law also requires Iowa’s Workforce Development Board to define and update annually a list of high-demand jobs in the state.

“We are looking at what fields on the whole really have a need for additional workers,” Iowa Rep. Chris Hall says. “And how we partner somewhere between the public and private sectors to give people additional training or to give them the additional support structures.”

In 2018, the Legislature appropriated about $3 million for Future Ready, but the estimated price tag for all of the programs is $18 million. Lawmakers will debate full funding during Iowa’s upcoming legislative session.

“I know that there was some talk last year about how we were going to find the budget for it, but I think we need to get past that and fund it,” Best says. “It’s a priority. It’s going to be very important as far as where the state goes in terms of filling jobs.”

Rep. Hall, Best’s colleague on the other side of the aisle, says Future Ready “was thoughtfully done,” and has the support of legislators in both parties. But he agrees that funding remains a challenge.

“We want to make sure that there’s a way to phase it in over a period of time and make sure that the highest priorities are met first,” he says. “$18 million is a sizable price tag considering we’ve had trouble funding some basic services, like Medicaid and public K-12 schools, over the last couple of years.”

For Best, one of the most promising parts of Iowa’s new investment is the opportunity it gives local communities, including some of the state’s rural areas that are struggling the most with a skills and talent gap: “We want to take the needs of the employers in the community and make sure those area community colleges and training organizations can provide formalized training.”

Thinking beyond four-year degrees

Sen. Horn is hoping Michigan’s Marshall Plan for Talent is only part of a broader rethinking about college and careers. He recalls a conversation in which a college student asked him what could be done to reduce the cost of his tuition. Horn’s response: “Is that the right question to ask? Does the college have value for you? Maybe that’s what we need to be asking.”

Tight labor markets and rising college debt are helping drive this conversation.

“Whatever we do to fix this [workforce]problem, it has to be high school, plus,” Horn says. “Whatever your career calls for, go out there and do it with confidence, but don’t go into college blindly.

“We have to stop this madness of going to college just for a general education.”

Best says one objective of the Future Ready Act is to expand choices for young Iowans.

“A lot of our high school kids are graduating and automatically thinking that to be successful, they have to go on to a four-year college,” he notes. “I graduated from high school in 1978, and the big thing for me was to get away and get a four-year degree.

“At that time the college debt was not so bad, but it’s a different world now. Now you have this college debt that is sometimes six figures, and you don’t have a major that’s going to pay very well. It’s a problem.”

How can states better promote these middle-skill pathways as an alternative?

For starters, Ridley suggests collecting concrete data on the career opportunities, and then sharing it with young people and their families: “Get better information on wages and the career prospects that are available to workers,” Ridley says.

“Develop an information source and a very granular set of data,” he adds. “Not just generally what you can get with an associate’s degree or a B.A., but what you can get with an A.A. in engineering technologies or in mechatronics, and even more specifically, which of those programs in Michigan or in Indiana or in Illinois are going to be the best bet for you.”

Promoting jobs in the skilled trades

Horn’s concern is that with such an emphasis on students attaining bachelor’s degrees, “we left the skilled trades behind.” The need in Michigan for more skilled professionals — in areas such as construction, information technology, health care and manufacturing — led to Horn’s sponsorship of the Going PRO Talent Fund (SB 946). Signed into law earlier this year, this measure codified, and renamed, an existing fund.

Between 2014 and 2018, that fund issued more than $70 million in grants to 2,200 companies across the state. It is credited with creating 14,000 jobs and retaining another 56,000. Under the new Going PRO name, the state will make $30 million in grants available in 2019 to employers.

The funds are to be used for short-term training that addresses a skilled-trades gap in Michigan’s workforce and that provides participants with an industry-recognized credential. Employers partner with community colleges, universities or other organizations to deliver the training.

“We tried to make it as stable and as predictable as we could without taking away flexibility for the people who are actually working the program,” Horn says. In addition to the technical training, the Going PRO Talent Fund sets aside dollars for management training, thus helping workers move into low-level management or foreman positions.

Horn acknowledges that Going PRO and the Marshall Plan for Talent are only part of the solution to meeting Michigan’s workforce needs — pieces of a “very big, 2,000-piece puzzle,” he says. Policies that address quality of life and that make Michigan’s communities more attractive to people matter as well.

Hall notes a similar challenge in Iowa, saying the skilled-workforce question is “very important,” but “not a silver bullet.”

“Iowa is growing, but at a slower pace than many other states, and so we see a lot of younger people who are leaving the state and choosing not to work here after they finish high school or college,” Hall says. “On the one hand, there’s a question of how we increase the share of our overall workforce that has some additional education or work credential, and then the other piece of it is how we grow the state’s population on the whole.”