Getting out the youth vote: Four trends in turnout, state programs, and new laws and legislation

1. In 2018, there was an uptick in turnout among young voters

After years of mostly declining participation levels among younger voters in midterm elections, a big change occurred in 2018 — turnout rates among the nation’s 18- to 29-year-olds soared. This trend occurred across U.S. states and regions, according to data collected and released in April by The Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement. That data includes estimates from 34 U.S. states, including nine in the Midwest (see table).

Between 2014 and 2018, the center notes, double-digit increases in younger-voter turnout occurred in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Nebraska and Ohio. In Minnesota, the rate reached 43.7 percent, highest in the nation.

“When you put this into the perspective of the past quarter century, a 10-point jump is pretty dramatic,” notes Abby Kiesa, the center’s director of Impact. Perhaps most significantly, too, the rise in turnout among younger voters eclipsed turnout increases among the general electorate.

Was 2018 simply an outlier year, or did it mark the beginning of an era in which more younger voters will participate?

“I think we have to be a little cautious in how we interpret last year’s results,” says professor Elizabeth Bennion, founding director of the American Democracy Project at the University of Indiana-South Bend.

She notes that the past election cycle had several turnout-boosting features — for example, young people’s strong feelings about the president, an unusually high level of peer-to-peer outreach (via social media platforms) about voting, and the decision by various national organizations (on issues such as gun control) to target participation by young people.

Yet still, a smaller percentage of younger voters cast ballots in 2018 than the general electorate.

2. The factors behind the ‘age gap’ in voter turnout

People who own homes, are married, pay property and income taxes, and feel a deep connection to their community are more likely to vote. Many teenagers and people in their 20s don’t match part or all of this profile — a fact that helps explain the longstanding age gap in voting rates, Bennion says. “Young people also are less likely than older people to see voting as a civic duty,” she adds.

Another reason for the disparity: Candidates, political parties and other groups have tended to ignore this age cohort in their voter-mobilization campaigns. “A young person doesn’t have a voting history, and doesn’t have a reliable partisan history, so for a long time, politicians were less likely to reach out to young people to vote,” Bennion says.

3. States go to schools to reach new, soon-to-be voters

Young people, though, are the focus of various state initiatives, often run through secretary of state offices. (The secretary of state is the chief elections official in every Midwestern state except Illinois and Wisconsin.)

Last year in Iowa, for example, close to 40,000 young people (many not yet of voting age) cast ballots at their local high schools as part of the Iowa Straw Poll, a mock election that in

cluded the races for governor and the local U.S. House seat. Candidates for these positions posted special video messages for students participating in the mock election. The Minnesota secretary of state’s office runs a similar program known as Students Vote. Local schools decide on how the election will be held, but the secretary of state provides the ballots, lesson plans for teachers, and “I Voted” stickers for students.

“We want young people to think of themselves as voters even before they are eligible to vote,” Secretary of State Steve Simon says. In 2018, the Students Vote program had participation f

rom 120,000 young people across 290 Minnesota high schools. Sixty-eight colleges, meanwhile, took part in the secretary of state’s College Ballot Bowl, in which campuses compete to get the most students registered to vote.

4. New laws remove voting obstacles for young people

In every state except North Dakota, individuals wanting to vote must be registered, and this can be an obstacle for young people who either haven’t voted in the past or who are living somewhere new. Various new policies, though, have been implemented to make the process easier and more accessible.

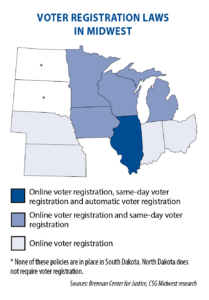

Last fall, with passage of SB 425, Michigan joined other Midwestern states (all but South Dakota) in allowing for online voter registration. In recent years, too, Illinois and Michigan followed Iowa, Minnesota and Wisconsin in permitting individuals to vote on the same day that they register — on Election Day and/or during the state’s early voting period.

According to the Brennan Center for Justice, Illinois is one of 15 states that offers “automatic voter registration”: Individuals who interact with a government agency are automatically registered to vote, unless they choose to opt out. Simon is pushing for automatic voter registration in Minnesota, as well as the preregistration of 15- and 16-year-olds — when they get their driver’s license, for example, or as part of a civics class.