Release of new ‘Census of Agriculture’ underscores changes and challenges for Midwest states and their farmers

Every five years, farm owners and operators are asked to complete a survey describing the characteristics of their farms. It takes almost two years for the U.S. Department of Agriculture to compile this data, which was released in April. Here is a summary of the notable trends and changes captured in the census about the Midwest.

1. Farmland acreage declining, but some Midwest states bucked this national trend

Total U.S. farmland is the lowest since the census began in 1910. Between 2012 and 2017, the nation lost more than 14 million acres of farmland — mostly pastureland and rangeland, in areas outside of the Midwest.

For several states in this region, in fact, the amount of farmland actually increased: North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska and Kansas led the nation, with each adding more than 600,000 acres of farmland between 2012 and 2017. Much of this gain was due to land leaving the federal Conservation Reserve Program and returning to production.

2. Fewer farms, larger farms: Consolidation of agriculture sector continues

Farms in the Midwest continue to consolidate: There are 4 percent fewer farms in the region, and farm size has grown by an average of 8 percent. This trend was not consistent across states, however. For example, North Dakota lost 15 percent of its farms, and that state’s remaining farms grew in size by 18 percent. In contrast, Ohio bucked regional and national trends, with its number of farms rising (by 3 percent) and average farm size declining (by 3 percent). This is similar to trends in some Northeastern states (as seen in the prior census) and may indicate growth in Ohio’s direct-marketing farms.

3. Use of conservation practices such as cover crops, no-till is on the rise in Midwest

The 2017 census collected data on production methods and found a rise in practices related to environmental protection and water quality. For example, the use of cover crops surged by 50 percent in the region. This increase is unique to the Midwest. In states such as Iowa and Minnesota, policymakers have been been boosting public investments in cost-share programs for farmers to adopt evidence-based conservation practices (these programs include state dollars to encourage no-tilling/cover-crop practices). Regionwide, between 2012 and 2017, the use of on-farm renewable energy systems such as wind turbines and solar panels increased by 136 percent.

is unique to the Midwest. In states such as Iowa and Minnesota, policymakers have been been boosting public investments in cost-share programs for farmers to adopt evidence-based conservation practices (these programs include state dollars to encourage no-tilling/cover-crop practices). Regionwide, between 2012 and 2017, the use of on-farm renewable energy systems such as wind turbines and solar panels increased by 136 percent.

4. Most farms are still family-owned; aging of Midwest farmers continues

The great majority of farms are still family owned and operated — 96 percent of them — and more young people and women are becoming farmers. However, the average age of the principal operator of a Midwestern farm increased from 55 in 2012 to 57 in 2017. (Nationwide, the average age was 50 in 1982.) Concerns about the continued aging of American farmers has led states to pursue various programs — for example, tax credits for beginning farmers in states such as Iowa, Minnesota and Nebraska.

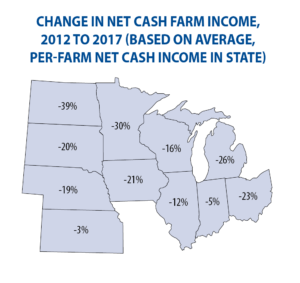

5. Recent years marked by precipitous decline in net farm income across Midwest

Net farm income fell dramatically between 2012 and 2017. Across the region, the census showed a decrease of 20 percent, with huge variances among the states. Across the region, more than 56 percent of farms had negative cash farm income, signaling serious challenges for U.S. agriculture and rural communities. Those challenges include slumping commodity prices (due to record production and a glut of corn, wheat and soybeans on the global market) and higher levels of farm debt.

percent, with huge variances among the states. Across the region, more than 56 percent of farms had negative cash farm income, signaling serious challenges for U.S. agriculture and rural communities. Those challenges include slumping commodity prices (due to record production and a glut of corn, wheat and soybeans on the global market) and higher levels of farm debt.

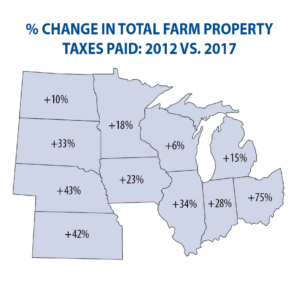

6. Farm expenses mostly declined, but property taxes cost farmers more

Farm expenses declined in most categories, with the notable exceptions of labor costs and property taxes. This rise in property taxes occurred while farm income was falling in many states (see #5 above). According to the census, between 2012 and 2017, property taxes increased by at least 25 percent in Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Nebraska, Ohio and South Dakota (as high as 75 percent in Ohio). In 2017, some state legislatures passed measures to curb these increases in property taxes. Ohio modified how the state’s agriculture use valuation should be calculated while also reducing taxes on land enrolled in conservation programs. Indiana legislators, meanwhile, adopted a series of tax relief measures for farmers — for example, changing the base rate and reducing the lag time for when changes in commodity prices are accounted for in the property tax formula. With policy changes like these and decreasing commodity prices, farmland taxes are expected to be lower in the next census.