MLC Chair’s Initiative | 2019 | Civic Engagement

Action plan for ‘action civics’: Legislators learn how states, schools are reimagining instruction in government and citizenship

Four years ago, the state of Illinois began requiring high school students to take at least one semester of civics. Most other states already had a similar instructional mandate in place, at least at first glance.

But the details of HB 4025 made it stand out from other requirements across the country, and they’ve since led to some big changes in how civics is being taught in Illinois.

In July, at the Midwestern Legislative Conference Annual Meeting in Chicago, the region’s lawmakers learned about some of those changes during a session on the importance of civic engagement, which is the subject of this year’s MLC Chair’s Initiative of Illinois Sen. Elgie Sims Jr.

“Civic engagement is much more than voting and volunteering, although those are the two things that we can measure quite well,” Sterling Speirn, a senior fellow and former CEO of the National Conference on Citizenship, said to legislators. “It’s also how people interact with one another, in their families, in their neighborhoods and in their communities.

“In places where there is good civic health, strong social capital, there is a correlation with lower crime rates, better public health, stronger workforce development, economic resiliency, better mental health, reduced mortality. … It almost sounds like a miracle cure.”

If so, it’s not surprising that legislative proposals around strengthening civic education have been commonplace in recent years, especially after years in which the subject was de-emphasized in favor of other subjects.

“It’s a bipartisan issue,” Speirn said. “In fact, I don’t know that you’re going to find anyone who is against civics education.”

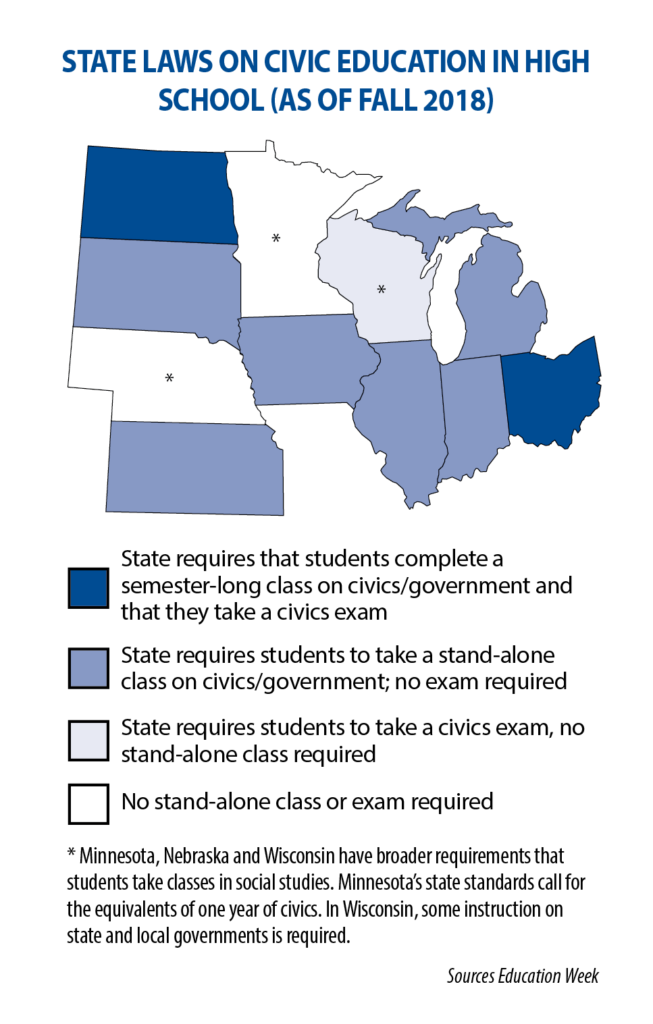

States have taken different approaches, however.

In North Dakota, Ohio and Wisconsin, state laws now require high school students to take a civics education test. In Wisconsin, for example, students must take a test that includes the 100 questions given to individuals applying for U.S. citizenship. To graduate, each student must correctly answer 65 of those questions.

Illinois, on the other hand, included no such testing mandate with HB 4025.

In fact, that law is often cited because of a very different type of requirement. The content of civics classes must go beyond learning the facts and figures of U.S. history and government; it must also give students the chance to discuss current issues, as well as take part in service-based learning opportunities and simulations of democracy.

Legislators also included language allowing school districts to “utilize private funding … for the purposes of offering civics education.” The result: a new public-private partnership (much of it led by the Illinois-based McCormick Foundation) to implement the state mandate, train teachers, and spread evidence-based practices in civics instruction.

This year, Illinois legislators passed a bill (HB 2265, signed by the governor in August) requiring that at least one semester of civics be taught in middle school. It, too, envisions public-private partnerships to help with implementation.

Illinois’ new direction for civic education takes a similar approach to the work being done by groups such as the Mikva Challenge. Through Mikva, students in Illinois get experience on campaigns and in legislative offices, serve on youth councils that advise local school boards and government, and work as election judges. The organization, too, is one of the outside groups helping bring an “action civics” curriculum to classrooms.

The organization was founded by Abner Mikva, a former judge and local congressman from the Chicago area, and his wife. Its mantra: “Democracy is a verb.”

“What we mean by that is that you have to learn democracy by doing it,” Michelle Morales, CEO of the Mikva Challenge in Illinois, said to legislators. “You can’t sit in the classroom and read about it.”

The MLC session’s third panelist was Heather Van Benthuysen, director of social science and civic engagement for Chicago Public Schools. She spoke of Illinois’ new law, but also said it’s only a start for how schools are now approaching civics instruction.

“The skills and habits that you need to flex your democratic muscles can’t be learned in only a semester-long or yearlong course,” Van Benthuysen said.

It takes a “360-degree commitment” from schools, she said, meaning civic engagement is incorporated across different subject areas and students get a meaningful say in school decision-making.

For that semester-long class on civics, CPS is emphasizing the importance of problem- or service-based learning (identifying a problem in the community and working to fix it) and learning to engage in civil debate over controversial issues.

Implementation can be a challenge.

“Across the country, teachers feel pressure from parents and administrators not to engage in current and controversial issues, out of a fear of appearing partisan,” Van Benthuysen said.

But perhaps the renewal of a meaningful civic education is one way toward less hyper-partisanship.

“It’s a challenging time in politics now because of what’s happening in the social arena,” Speirn said to legislators.

Yes, we live in a time of divisiveness, he argued, but the root causes are a “crisis of isolation, of loneliness, disconnection and alienation.” By having young people flex those “democratic muscles” — by talking to people with whom they disagree, by engaging in the community around them — schools can have a role in producing informed, active citizens who feel more connected to others, Speirn said.

Illinois Sen. Elgie Sims has chosen civic engagement as the focus of his Midwestern Legislative Conference Chair’s Initiative for 2019. A series of articles will be written in 2019 in support of this initiative.