After decades of delay, shipments of spent fuel from Midwest’s nuclear plants may take different route

State governments have lots of experience coordinating and planning shipments of radioactive waste with the federal government, but little to none working directly with the nuclear industry on shipments. That may change in the not-so-distant future.

The reason: For decades, the federal government has been unable to find a permanent repository to store the nation’s spent fuel from nuclear power plants, and the industry is now trying to take matters into its own hands.

Private-sector plans to create consolidated, interim storage facilities in New Mexico and Texas are now before the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. With licensing approval from the commission, the owners of these facilities could begin to receive shipments of spent nuclear fuel from nuclear plants owned by their subsidiaries as well as other utilities until a permanent federal repository is completed.

Potential of private-sector shipments

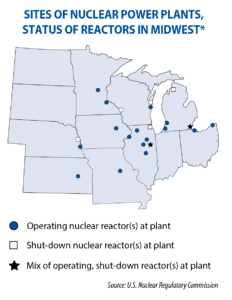

Across the Midwest (Missouri included), as of the end of 2017, more than 20,300 metric tons of spent nuclear fuel was being stored at 23 operating or decommissioned nuclear power plants in nine states.

The plan always has been to get this highly radioactive waste off-site.

In 1987, the U.S. Congress designated Nevada’s Yucca Mountain as the permanent repository site for the spent fuel from the nation’s power plants. But a mix of factors — including years of opposition from Nevada and the Obama administration’s decision to reject the Yucca site in 2010 — means a storage solution from the federal government is nowhere in sight.

For utilities, as long as the spent fuel is left at their facilities, they must provide 24/7 security and cannot finish the work of cleaning up the sites of decommissioned plants that no longer generate electricity. In northern Illinois, for example, a decommissioned plant keeps a state park on the shores of Lake Michigan divided in two. The Big Rock Point plant in Michigan was decommissioned more than 20 years ago; its land cannot be redeveloped until there is a place for the spent fuel to be sent.

Private-sector shipments to the New Mexico and Texas facilities could resolve this problem of spent fuel being stranded at shutdown sites, but also create new challenges for states.

“States bear the primary responsibility for protecting the health and safety of the public and the environment,” notes Kelly Horn of the Illinois Emergency Management Agency and a member of The Council of States Government’s Midwestern Radioactive Materials Transportation Committee.

To date, states have met this responsibility in partnership with the federal government.

In the Midwest, for example, through the work of CSG’s Midwestern Radioactive Materials Transportation Project, states have a great deal of experience working with the Department of Energy on large-scale shipments of radioactive waste (mostly waste being moved from the nation’s defense sites and from domestic and foreign research reactors).

Under federal law, for large-scale shipments of spent fuel from nuclear power plants to a federally operated repository, the Department of Energy would have to provide training funds and technical assistance to states and tribes affected by the shipments.

“For transportation of spent nuclear fuel [from power plants], the work of training emergency-response personnel, monitoring shipments, conducting inspections, enforcing state-specific regulations, and providing escorts becomes the responsibility of the states,” Horn notes.

However, no such legal obligations apply to private-sector shipments.

Some states in the region may be able to recoup some of their shipment-related activities through fees (see map). However, these fees would only be collected when shipments begin; as a result, no funds would be available for advanced preparations and training.

Earlier this year, members of the CSG Midwestern Radioactive Materials Transportation Committee participated in an industry-led “tabletop exercise” at the Prairie Island Nuclear Power Plant in Minnesota. The event helped to begin a dialogue between the industry and state, tribal and local stakeholders regarding private-sector shipments of spent nuclear fuel.

In November, the committee will host an exercise of its own.

“Communication [between states and industry] has to occur early and often to ensure the shipping strategy is complete and thorough,” Horn says.

Natural gas production in the Utica and Marcellus shale plays has helped bring down prices in Ohio. Across the country, too, the availability of cheap natural gas has caused some utilities to shut down nuclear reactors in favor of gas plants, or to invest in new gas-fired plants rather than nuclear-generating facilities.

Even the newest nuclear plants in the United States have now been operating for more than 30 years, and only a few applications have been filed to build new ones. In the Midwest, Iowa’s only nuclear plant is scheduled to be shut down in 2020. Twelve nuclear reactors in the region have been or currently are being decommissioned.