No shortage of ideas: In recent years, states have adopted many new policies to attract new teachers — and keep them in the classroom

As a library media specialist in a Minnesota middle school, Rep. Mary Kunesh-Podein comes across potential teachers all the time. It’s the students themselves. “At our school, students are often mentoring other students, and we are flabbergasted at what we see,” she says. “They have the patience. They have the understanding. They connect well with that other student.

“And we think, ‘This kid would make such a great teacher.’”

As a legislator, Rep. Kunesh-Podein also thinks about this: What state policies could expose more of these young people to the profession, and get them on a path to becoming a teacher? One idea, part of a legislative proposal in Minnesota this year (HF 824/SF 1012), is to bring college-level, credit-bearing Introduction to Education classes into the state’s high schools; another is to identify and eliminate barriers (financial or otherwise) that stand in the way of lower-income individuals getting certified to teach.

Attracting more teachers, as well as retaining them, has been on the minds of many state policymakers in the Midwest, as evidenced by the burst of new legislative proposals, laws and investments over the past few years. A few examples:

- Iowa is now spending $160 million annually on what it says is the most extensive teacher leadership and compensation system in the country.

- Kansas and Minnesota are providing help for school paraprofessionals interested in pursuing teacher certifications.

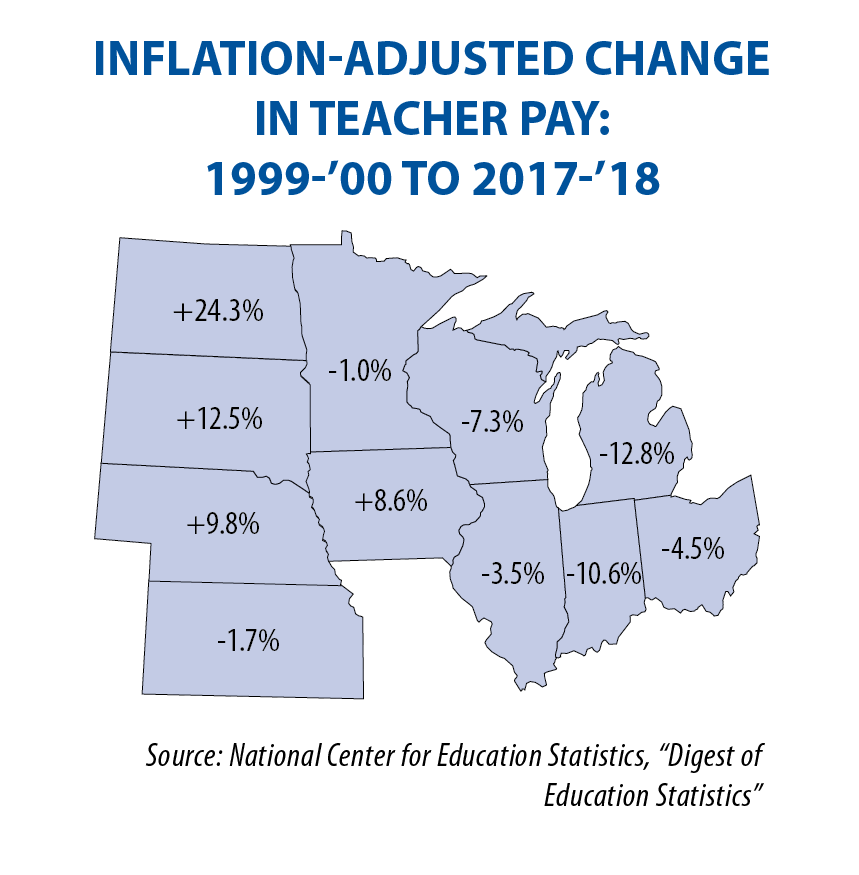

- South Dakota recently raised its state sales tax for the purpose of boosting teacher pay, and in Illinois, lawmakers this year set a minimum annual salary for teachers (it gradually reaches $40,000 by the 2023-24 school year).

- In Indiana, legislators passed bills this year that provide for new teacher-residency programs and career ladders for instructors in select school districts.

Taken together, the list of recent actions in the Midwest reflects the kind of comprehensive approach needed to address teacher shortages over the long term, says Ryan Saunders, a policy adviser at the Learning Policy Institute. “Pay alone isn’t going to get you all the way there,” he says, and neither is simply increasing the supply of licensed teachers.

“It’s also about how we keep the teachers we have — how to prevent the revolving door we see now because of high attrition rates,” Saunders adds.

Annual teacher attrition across the country is about 8 percent, according to the institute, and two-thirds of these individuals leave the profession for reasons other than retirement. Among new teachers, an October 2018 national study by the University of Pennsylvania found, 44 percent leave within five years.

Leadership opportunities, pay grow for teachers in Iowa

In an August 2018 report of the Learning Policy Institute, Saunders and his co-authors highlight strategies at the leading edge of efforts to strengthen the educator workforce. One of the states singled out multiple times: Iowa. Since passage of a law in 2001, that state has required (and helped) school districts provide more mentoring and support for first- and second-year teachers. And starting with a law enacted in 2013, Iowa has implemented a $160 million Teacher Leadership and Compensation System.

That law raised pay for beginning teachers, while also establishing a process for school districts to reward veteran, effective instructors. “We now have more than 10,000 teachers in compensated, defined leadership roles,” Iowa Department of Education Director Ryan Wise says. That is equal to about one-quarter of Iowa’s educator workforce.

Subject to approval by the state (based on standards set out in the law), every Iowa school district has established its own leadership system. Teachers, for example, may get more pay for becoming schoolwide instructional coaches, serving as mentors to newer teachers, helping integrate technology into every school classroom or designing professional-learning opportunities.

Along with giving teachers the opportunity to earn more pay, Wise says, the new system has fostered more teamwork among teachers — a change that can not only help the work climate in a school building, but also improve instruction through the sharing of best practices.

“All the [classroom] doors are open, teachers are constantly working together,” Wise says about the shift in culture brought about by Iowa’s Teacher Leadership and Compensation System. “Students never bat an eye when they see a bunch of adults walking into their classrooms, because that’s just how their buildings function now.”

In his home state of Indiana, Sen. Jeff Raatz has visited schools that have implemented systems similar to Iowa’s, and he liked what he saw ¬— particularly the chance for providing more supports for incoming teachers and additional opportunities for established instructors. This year, the Indiana General Assembly created a $3.5 million grant program (HB 1008) for select school districts that create new “career ladders” and leadership and compensation opportunities for teachers.

That new initiative was one of several legislative actions taken in Indiana, where teacher pay and shortages were two of the most talked-about policy issues of 2019. Legislators, for example, included $150 million in Indiana’s biennial budget to help school districts pay down their pension liabilities, with the idea that districts would then have more money to raise teacher pay. Under another new law (HB 1003), the legislature also set a new goal for every school district — have at least 85 percent of its spending go to the classroom.

Lastly, Indiana will begin investing state dollars in teacher residencies (HB 1009), one of the evidence-based strategies highlighted in the Learning Policy Institute’s 2018 report. These residencies give prospective teachers a full year of intensive, preservice experience under the guidance of a mentor teacher. They also typically provide compensation for the prospective and mentor teacher. The hope, Raatz says, is that a stronger induction system will lead to greater success in the classroom among new teachers and “prevent them from walking away after the first year.”

Teacher shortages: ‘Not distributed equitably or evenly’

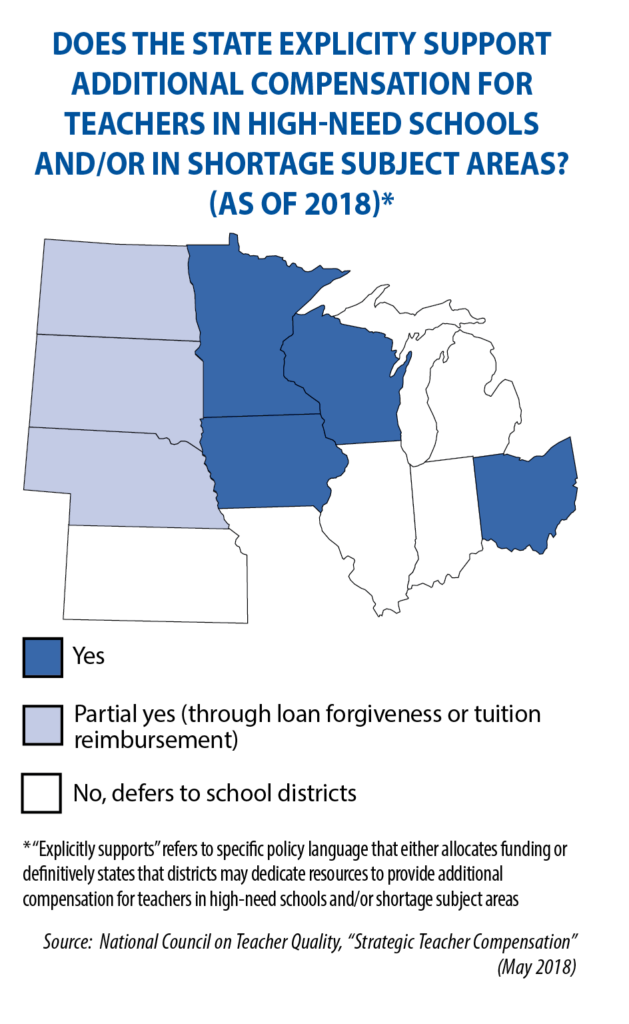

States not only should be comprehensive in their policy approach (meaning they address everything from teacher recruitment and retention, to compensation, school climate and licensure), Saunders says, they also should be strategic. “[Teacher] shortages are not distributed equitably or evenly,” he says.

Instead, shortages tend to be most acute in sparsely populated areas, as well as in schools with higher numbers of low-income families and students of color. The appropriate policy response from states, then, may be to establish targeted induction, compensation and incentive programs. In Nebraska, for example, a state-funded initiative offers loan forgiveness to individuals who teach in high-need subject areas, higher-poverty schools and rural parts of the state.

Some states also provide incentives for teachers with National Board Certification (a voluntary, advanced teaching credential) to teach in higher-need schools. Illinois Sen. Andy Manar says that was one of the approaches that his state took this year.

“We went a little a deeper than just investing more in our budget for the National Board Certification Program,” he says. “We said that we want that certification to happen first in our Tier 1 [underfunded or lower-performing] schools. We want to provide incentives to teachers in those schools to go beyond their bachelor’s degree, and then encourage them to stay in their school because it’s where they are needed the most.”

Over the past two years, Manar and other legislators have adopted a series of new laws that he says were needed to “lift up the teaching profession” in Illinois. None were more important, he adds, than establishment of a new minimum teacher salary (HB 2078).

“We have teachers in Illinois that would qualify for Medicaid; that’s a grave injustice,” he says.

Starting in 2020, annual teacher pay must be at least $32,076; the minimum salary rises to $40,000 by 2023. “Now a young person has a guaranteed salary, no matter where he or she teaches,” Manar says. “That does so much for the psychology of how decisions are made for prospective teachers.”

‘Grow Your Own’ programs help schools build workforce from within

Illinois law also now permits student-teachers to be paid (SB 1952), a move that could help individuals transition into teaching from another profession. Sen. Manar gives the example of paraprofessionals already working in a school and interested in becoming a certified teacher. “They can’t quit their job in order to come back as a licensed teacher,” he says.

Providing some kind of pay or stipend for the stint as a student-teacher removes a financial obstacle, and it’s one component of another emerging state strategy referred to as “Grow Your Own.”

Kansas has been experimenting with this approach by offering a “limited apprentice license” to individuals identified by a school district. For example, someone working in a school as a special-education paraprofessional now has an accelerated, alternative pathway to becoming a special-education teacher. While continuing his or her work as a paraprofessional, the individual is paired in the fall with a mentor teacher while taking coursework on special-education instruction. By the spring, he or she can be hired as a special-education teacher while taking more coursework.

In Minnesota, the state funds a $1.5 million Grow Your Own grant program that school districts can use in one of two ways: 1) provide tuition scholarships or stipends to paraprofessionals who are employed by the district and seeking a teaching license; or 2) encourage high school students to pursue teaching. The second option includes offering the kind of credit-bearing, Introduction to Education course that Rep. Kunesh-Podein wants more Minnesota high schools to be able to offer.

With both options, the grants are limited to school districts with more than 30 percent minority students, and Minnesota also has a separate program to help American Indians become teachers. “We want more teachers of color so that the kids have somebody in the front of the room who looks like them and understands their culture or the struggles that they go through,” Kunesh-Podein says. “The teacher, the student and the entire school benefit.”