Help for homeless students

This school population is at much greater risk of falling behind and not graduating; advocates say states can help with prevention, intervention strategies

Six years ago, with a $2 million legislative appropriation, Minnesota launched a pilot program to help some of that state’s most at-risk students — young learners who lack stable or adequate housing. The state began partnering with schools and local organizations to provide vulnerable families with subsidies that helped pay their rent over two school years. The goals: Stabilize housing and prevent homelessness, thus improving school attendance and, over the long term, academic performance among these students.

The early results, says Eric Grumdahl, were a “powerful signal” that this kind of intervention worked.

Ninety percent of the pilot program’s students with a known housing status were stably housed. (All of them had entered the program experiencing housing instability or school changes.) Further, these young people were more likely to be attending school on a regular basis than their homeless peers.

“That encouraged us to take this to a larger scale,” adds Grumdahl, who works for Minnesota’s Interagency Council on Homelessness and the Department of Education. The “larger-scale,” permanent program is now called Homework Starts with Home, and the Legislature appropriated $3.5 million for it this biennium as part of Minnesota Housing’s base budget. The hope among legislators is to reach more young people, and to stop what can be a destructive cycle — homeless students are much more likely to fall behind and drop out of school; individuals who don’t complete high school are at a much higher risk of homelessness as young adults.

“The more children have to change schools [because of housing instability], the further they fall behind,” notes Barbara Duffield, executive director of the nonprofit SchoolHouse Connection, which advocates for policies that help these students. “They’re losing time and they’re losing coursework. At the same time, they’re also losing attachments to friends and teachers, and all of those emotional pieces of stability.”

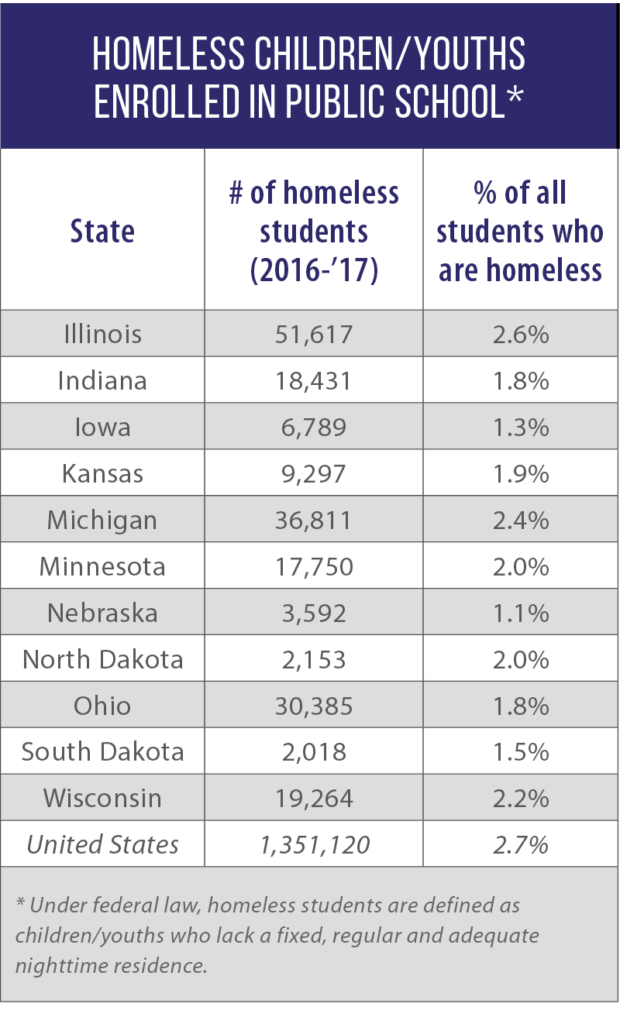

Barriers to success

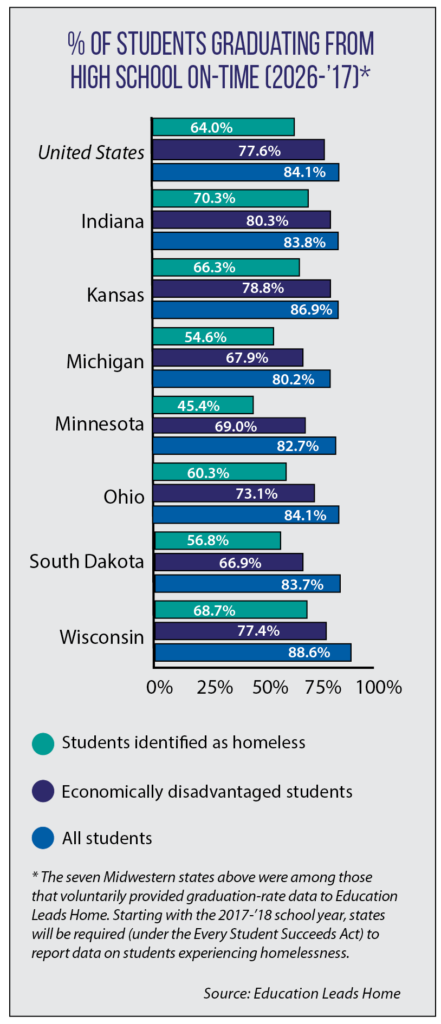

Not surprisingly, then, the achievement gaps between homeless students and their peers are wide. Nationwide, for example, less than two-thirds of homeless youths graduate from high school on time. That compares to 84 percent among all students, and 77 percent among low-income students who have stable housing. Surprising to many, Duffield notes, is the large number of students who have been identified by local school districts as meeting the federal definition of homeless. More than 1.3 million young people in the United States lack a “fixed, regular and adequate nighttime residence.”

At the start of the 2018-’19 school year in Minnesota, the state identified more than 8,000 students as experiencing homelessness in 78 of its 87 counties. (The state-by-state numbers in the table above are much higher because they identify students who have experienced homelessness at any point during a school year.) “I don’t think most people are aware of it, especially the kind of geographic dispersion we see,” Grumdahl says. “We’ve had legislators representing rural parts of Minnesota who are shocked when they see the homeless numbers for their communities.”

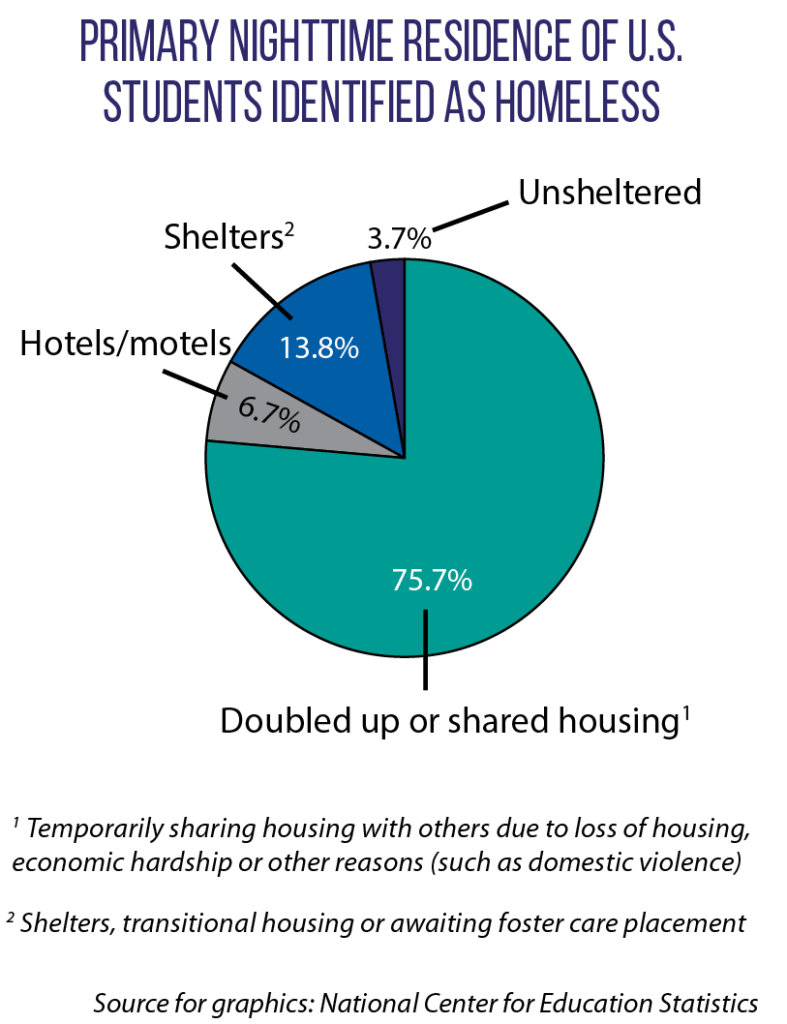

In every state, the homeless-student population includes young people who live in shelters, hotels or on the street, but a vast majority of this student population is in “doubled-up housing” — often temporary, and the result of economic hardships or circumstances such as domestic violence.

“It’s not just staying temporarily with a family; a lot of times it’s anybody who will take them in,” Duffield says. “They are extremely vulnerable, and at risk of abuse or neglect.”

“These are children who generally have been invisible in their schools and communities,” she adds. Some recent changes in federal education policy, though, are raising the visibility of this student population, while also requiring more of states.

Identification, prevention

Under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), states for the first time must track and report on the academic progress and graduation rates of students identified as homeless. “Previously, the focus of federal policy has been to make sure these students have school access and stability,” Duffield says. “The big change with ESSA is we’re going to track how well they’re doing.”

The federal law also requires school districts to reserve some of their Title 1 funds to support children and youths experiencing homelessness. This can include investing in school-based liaisons (who help identify students) or in transportation services that keep students at their school of origin.

“It’s a strong federal blueprint, but much of the action, where the rubber has to meet the road, is at the state level,” Duffield says. Examples of recent state actions include:

- a 2019 law in Indiana (SB 464) that helps unaccompanied youths take a high school equivalency exam and access identification documents that they need to secure stable housing; and

- new pathways for homeless students in Kentucky and Texas to complete coursework, earn partial credits and secure a diploma.

According to Duffield, Washington stands out among states for having the most comprehensive policy framework in place to help its population of homeless students. Every school in that state is required to have a liaison that helps identify these students, and then connect them and/or their families to services that can stabilize their living situations. (Under federal law, every school district must have a liaison.)

“Liaisons are lifelines for these children and families,” Duffield says. “They have a singular focus on this population. They train the school community that these children exist, what their needs are, what their rights are.”

Early identification can result in homeless prevention, and that is the goal of a new project being implemented by The University of Chicago’s Chapin Hall in a handful of school districts. This “Upstream” model relies on a mix of schoolwide surveys and early warning indicators (such as chronic absenteeism) to identify at-risk students. These young people and their families are then connected to appropriate community services that address “underlying risk factors before they escalate to crisis.”

The Chapin Hall project is based on a program from Australia that reduced the number of young people becoming homeless and dropping out of school. In Minnesota, meanwhile, university researchers will be tracking the impact of Homework Starts With Home. Will it stabilize students’ housing situations? Will it improve school attendance and longer-term educational outcomes?

More and more states are likely to be asking questions like these in a new era of education policy under the Every Student Succeeds Act. “It’s shining a light on how homelessness affects educational achievement, above and beyond poverty,” Duffield says.

State strategies to help homeless students: Three examples from the Midwest

Illinois schools get funding option to provide housing help

In 2017, Illinois legislators passed HB 2061 to help school districts provide housing assistance to a child who is “homeless or is at risk of becoming homeless.” This aid can go toward families’ rent, mortgage, or other unpaid bills and financial debts. Under the three-year-old law, a school district is able to use transportation funds for housing assistance if this is the most cost-efficient option. (Under federal law, homeless students have the right to remain in their school of origin if it is in their best interest; transportation must be provided to and from the school.)

Indiana enables youths to access documents, exams they need

For every state in the Midwest, a portion of the homeless-student population is “unaccompanied” — young people living on their own or with a caregiver who is not their legal guardian. Helping this group was one of the goals of Indiana’s SB 464, which was signed into law in 2019. It helps unaccompanied youths gain access to critical documents (such as birth certificates and photo identification) that they may need to secure housing or enter the workforce or higher education. Under the law, certain representatives of these youths (for example, from a school district, a nonprofit group or government entity) is authorized to get these documents. They also can register a young person to take the high school equivalency exam, free of charge.

Minnesota provides housing assistance for college students

According to the national nonprofit organization SchoolHouse Connection, Minnesota is one of a handful of states where legislation was passed in 2019 to help college students experiencing homelessness. Under SF 2415, the Legislature appropriated more than $500,000 for a matching grant program between the state and postsecondary schools. That money will be used “to meet immediate student needs that could result in a student not completing the term of [his or her] program.” Legislators also allocated $3.5 million over the next two years for Homework Starts With Home, which provides housing assistance to students experiencing, or at risk of experiencing, homelessness (see main article above for details).