State laws treat mother’s substance use during pregnancy as child abuse, but should they?

Twenty-two years after South Carolina became the first state to criminally convict a woman for child abuse for using crack cocaine during her pregnancy, only Alabama and Tennessee have joined it in criminalizing that behavior.

But almost half of all states — including every Midwestern state except Kansas, Michigan and Nebraska — con sider a mother’s drug use during pregnancy to be child abuse under civil child-welfare law, according to a December 2019 survey by the Guttmacher Institute, a New York City-based organization researching sexual and reproductive health rights policies worldwide.

sider a mother’s drug use during pregnancy to be child abuse under civil child-welfare law, according to a December 2019 survey by the Guttmacher Institute, a New York City-based organization researching sexual and reproductive health rights policies worldwide.

This type of statutory language, Guttmacher notes, provides grounds for the termination of parental rights.

Minnesota, South Dakota and Wisconsin also consider a mother’s prenatal drug use to be grounds for civil commitment (for example, required enrollment in inpatient drug treatment programs), according to the survey.

The survey also notes that if prenatal drug use is suspected, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin require health professionals to report it while Indiana requires pregnant women to be tested; Iowa, Minnesota, North Dakota and South Dakota require both.

Kansas and Nebraska have no reporting or testing requirements, the survey says.

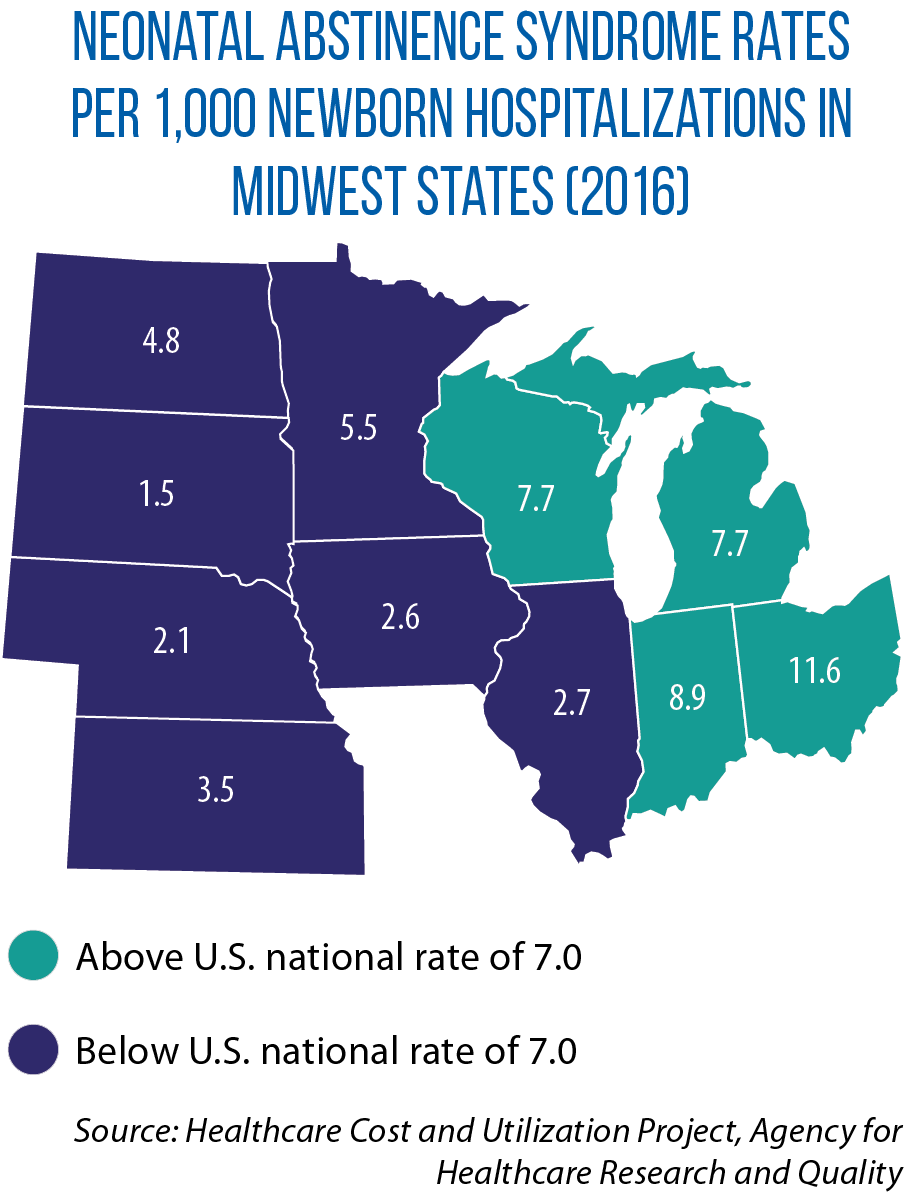

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates 15 percent of infants nationwide are affected by prenatal alcohol or illicit drug exposure, which can cause a wide range of physical and developmental challenges.

The Guttmacher survey details the mix of state strategies to address this public health problem — some include punitive measures such as forced admission to an inpatient treatment program, others fund programs that target help for pregnant women to overcome their addiction.

“Sometimes the effects of these bills are much more punitive than the intent,” notes Elizabeth Nash, senior state issues manager for Guttmacher.

For example, short of criminalizing prenatal drug use, she says, Wisconsin “has one of the most punitive laws in the country.”

That law, which dates from 1997, allows pregnant women to be subjected to forced treatment and detention if local government employees feel she “habitually lacks self-control in the use of alcoholic beverages, controlled substances or controlled substance analogs … to the extent that there is a substantial risk” to the physical health of her child.

This law was declared unconstitutionally vague in 2017 by a federal district court, but that decision was then vacated by a federal appellate court which ruled that the case became moot when the plaintiff moved out of the state.

Crucially, the appellate court did not rule on the merits of the district court’s finding, says Lynn Paltrow, founder and executive director of National Advocates for Pregnant Women.

This kind of legislation seems to address a serious problem, but the effect of it can be to discourage women from seeking help and treatment on their own, Paltrow says.

“What we need are health care systems that guarantee people confidentiality and security whenever they seek care,” she says.

According to the Guttmacher survey, Illinois, Indiana, Minnesota, Ohio and Wisconsin have either created or funded drug treatment programs specifically targeted to pregnant women.

In addition, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Ohio, South Dakota and Wisconsin provide pregnant women with priority access to state-funded drug treatment programs.

In Illinois, for example, treatment services are available at no cost for individuals not eligible for Medicaid through the federal Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant — which targets pregnant women and women with dependent children, among others — and pregnant women seeking substance use disorder treatment are given priority admission status, according to the state’s Department of Human Services.

If treatment capacity is unavailable for a pregnant woman seeking services, interim services will be made available no later than 48 hours after she has sought treatment, according to the department.

Jon Davis is the CSG Midwest staff liaison for the Midwestern Legislative Conference Health & Human Services Committee.