Capital Closeup | COVID-19 pandemic makes virtual legislating a reality

Wisconsin holds virtual session days in April

In March, Senate President Roger Roth got the call to prepare for an unprecedented — but not unthinkable — event in the legislative history of Wisconsin. “Whatever you have to do,” he was told by Senate Majority Leader Scott Fitzgerald, “we need to be able to have a contingency plan in the midst of this coronavirus [outbreak].”

Roth’s job as presiding officer: Get the state Senate ready for a first-ever virtual meeting of the entire chamber, so that it could pass essential bills related to the COVID-19 pandemic while keeping its 33 members and legislative staff safe.

“I immediately called our legislative service agencies: our technology folks, our lawyers, our parliamentarians,” Roth says. “And from that point on, they haven’t stopped working.”

After much preparatory work, practice and dress rehearsals, actual virtual sessions of the Wisconsin Senate began being held in April.

“First, you want to protect the health and safety of our members, and one-third of [the senators] are 68 or older,” Roth says, noting that older people are at a higher risk of developing serious, potentially fatal, complications if exposed to COVID-19. “Just as important, in the midst of these extraordinary circumstances, people are looking for stability and want to be reassured. I think it’s important to show that even in these challenging times, our government, just like our people, will endure.”

Challenge of legislating, while social distancing

A little more than a decade ago, Wisconsin legislators were thinking about and planning for just this kind of scenario. In 2008, a joint legislative committee was formed to study new policies that could help ensure continuity of government. One of its recommendations, which became law a year later, was to allow the Wisconsin Assembly and Senate to hold virtual sessions when in-person meetings in Madison were impractical or dangerous “due to an emergency resulting from a disaster or the imminent threat of a disaster.”

Such a disaster came to Wisconsin, and the entire nation, in 2020.

Early on in the COVID-19 pandemic, the actions of the nation’s governors received considerable attention, as they used their emergency powers to close schools, impose stay-in-shelter orders, limit travel and more. But in a system that relies on three functioning branches of government, the difficulties of legislating during periods such as the COVID-19 pandemic meri special consideration as well, says Gary Moncrief, a distinguished professor of political science at Boise State University and one of the nation’s leading authorities on state and local governments.

“State legislatures are so different in terms of the challenge this creates for them when you compare it to other institutions at the state level, as well as any other institution, save for Congress, at the federal level,” he says.

Most legislatures in the Midwest have more than 100 members, for example, and give-and-take interactions among these elected officials are central to what they do. The idea of these legislators conducting the people’s business virtually — away from one another and the public — is not optimal, but it needs to be looked at as a necessity to keep government functioning in certain times of crisis, says Norm Ornstein, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.

“The way to deal with it is you make any remote meeting or voting temporary, occurring only when it’s absolutely necessary, and for a specified period of time that is renewable [by legislative leaders or the legislative body],” Ornstein says.

The language in Wisconsin’s 11-year-old statute on virtual meetings includes those kinds of limitations. It provides a definition of “disaster,” requires a change in legislative rules by members of the Assembly and/or Senate, and sets out specific requirements for virtual sessions:

- Authenticate the identity of each legislator and his or her actions, including voting.

- Ensure that each legislator has access to documents and can hear or read comments made by other members.

- Allow the public, “within technological limits,” to “monitor the proceedings.” (In Wisconsin, Roth says, this is being accomplished via WisconsinEye, the state’s public affairs TV network.)

At the start of this year, Wisconsin was the only state in the region with a statute specific to remote meetings of its state legislature — both allowing them to occur and establishing clear rules for how lawmakers must proceed, according to a CSG Midwest survey of legislative service agencies. In recent weeks and months, though, virtual sessions have been used or considered in other states.

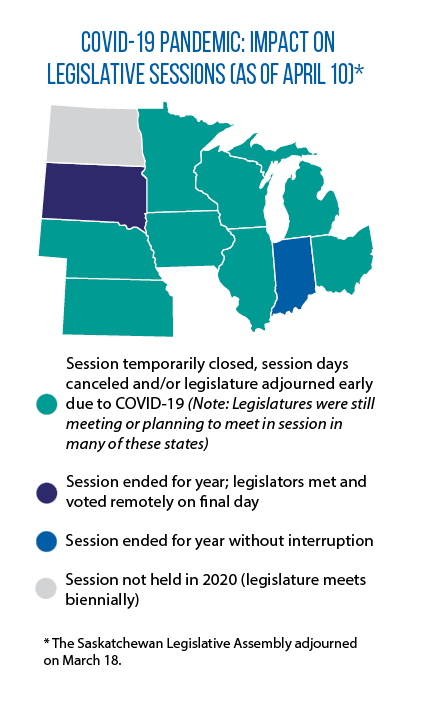

On South Dakota’s final day of the 2020 session (“veto day”), legislatures met remotely after a suspension of legislative rules, the Sioux Falls Argus Leader reports. In Minnesota, remote committee meetings have been held, and the House temporarily changed its rules to “allow for the use of distance voting, remote electronic voting or voting by other means … to protect the health and safety of the public, staff and members.”

In Wisconsin, Senate President Roth’s plan was to have about 10 people (legislative leaders and staff such as the chief clerk) still meet in the Capitol, with the Senate chamber sanitized and taped off to ensure social distancing, and to have all other members participate remotely, via state-issued laptops.

“We could pull it off going totally virtual, but just knowing how things work, we thought it was important to have those leaders be able to look at and talk to each other in person,” Roth says. “It facilitates a much smoother process.”

Leaders grapple with legality of remote sessions

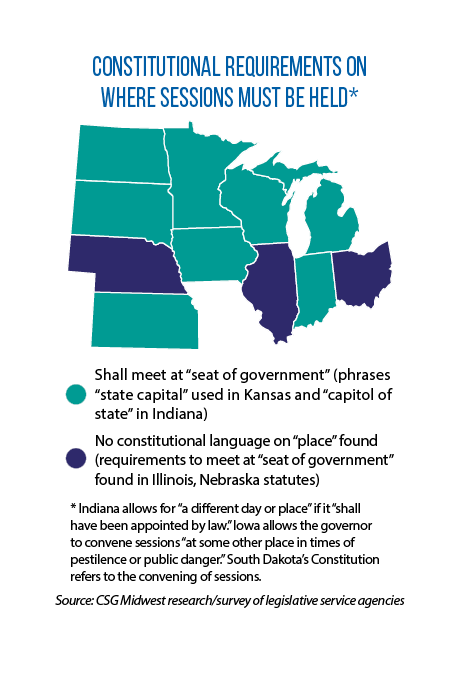

In other states, there have been legal questions to consider before holding remote legislative sessions. For example, most of the Midwest’s state constitutions have language stating that the legislature “shall meet” at the “seat of government.” Do virtual sessions conflict with this constitutional (or statutory, in some cases) language?

States also often have requirements designed to ensure public access, including constitutional or statutory language in states such as Indiana, Michigan, Nebraska and Wisconsin that call for the “doors of the legislature” to be open.

In Illinois, Senate President Don Harmon says, “most members were in agreement that if we can avoid bringing people together — not only members, but staff and interested constituents — it would be in everyone’s long-term interests.”

“The question was, can we do a remote session without first meeting once [in person] to pass a law authorizing it?”

Harmon, meanwhile, formed 17 bipartisan committees to study myriad issues arising from the COVID-19 pandemic, including government continuity.

“Should we expressly authorize some sort of virtual meeting of the General Assembly? Should we amend our Open Meetings Act to ensure our state agencies and our local governments can proceed with their business without jeopardizing the health of their members?” Harmon asks. “Those are among the first things that I think need to be tackled.”

In Michigan, Senate Majority Leader Mike Shirkey says his state’s statutes and Constitution provide a clear direction for its full-time Legislature: meet in person, not remotely. “The intent of our statutes and the words in our Constitution are very clear, and that is so our citizens can confront the people making decisions,” he says.

The Michigan Legislature has curtailed in-person sessions and authorized committees to do some work remotely, but in early April, lawmakers convened for one day in Lansing. Precautions were taken: Many members wore face masks, temperatures were taken of people entering the state Capitol, and only a small number of House members were allowed in the chamber at any given time, the Detroit Free Press reports.

This is not the first time in American history that state legislatures have had difficulty finding ways to meet and conduct the people’s business. During the Revolutionary War, political scientist Peverill Squire says, legislatures had to “stay on the move and not get captured.” Capitol buildings have sometimes burned down, and legislatures have had to flee seats of government due to outbreaks of disease.

“Most of the state’s constitutional provisions can be interpreted to allow for legislatures to meet in a way that is different than traditional fashions,” Squire says. He adds that the judicial branch typically defers “to legislatures and allows them to make decisions about internal operations.”

And more than any time in U.S. history, technology provides a tool to ensure legislative continuity.

“It’s a matter of making some temporary adjustments to legislative rules, and making sure everyone who is a member of the body has the opportunity to participate,” says Squire, a professor at the University of Missouri and leading national expert on state legislatures.

Helping constituents, checking governors’ powers

In many states, session days and weeks have been suspended due to COVID-19. Other parts of the job of legislator, though, never stopped.

“It’s even more important to be engaged with our constituents because the acuity of their problems has increased dramatically,” Harmon says. “And we’re being posed with some very novel questions.”

In March, for example, Harmon was trying to help get a constituent home from Peru. The constituent was stuck there due to COVID-19-related travel restrictions.

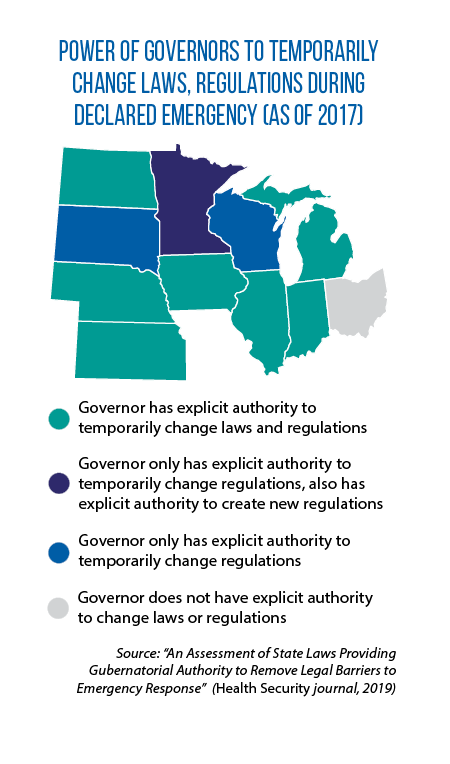

Another critical role for legislatures: checking the power of the executive branch. For example, it’s left to legislatures to continue or rescind governors’ emergency orders (see table).

“Having untethered powers is a very dangerous thing, especially given what’s happened with the size and scope of government,” Ornstein says. “To completely lose that check on behavior, which can lead to corruption or political manipulation, is a big mistake in a democracy.”

Capital Closeup is an ongoing series of articles focusing on institutional issues in state governments and legislatures.