2020 MLC Chairman’s Initiative on Literacy

Lack of knowledge in personal finance increasingly seen as public policy challenge for states, provinces

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, one in five 15-year-olds doesn’t understand basic financial concepts. For those young people, too, some very important financial decisions lie only a few years ahead — how to save and invest, how to choose between college and work, how to borrow wisely, how to manage debit and credit cards, etc.

One response by states to the challenge of improving personal financial literacy: Require more of high schools and students in this subject area, with the hope that it lays the groundwork for long-term economic success.

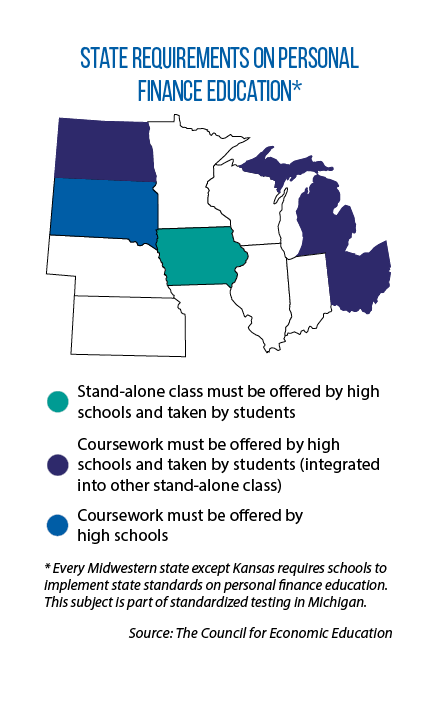

“Well-implemented state financial education mandates lead to a clear improvement in financial behaviors,” according to a 2019 report by the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Such mandates are not common in the Midwest; only Iowa, for example, requires that its high school students take a stand-alone course before graduation, the result of state legislation (SF 2415) passed in 2018. (An enacted measure from 2019, SF 139, delayed implementation until 2020-’21.)

Five other U.S. states have similar stand-alone requirements. The council refers to these laws as the “gold standard,” but it’s more common for states to instead mandate that schools offer coursework in personal financial literacy as part of a class such as economics or civics.

Such requirements aren’t the only options for policymakers, either. In Saskatchewan, for instance, the Ministry of Education recently developed two new courses (Financial Literacy 20 and 30) that any secondary school can offer as part of the school’s “practical and applied arts” credits required for graduation.

“Parts of those courses can be used all the way down to grade seven,” Assistant Deputy Minister Susan Nedelcov-Anderson says.

Developed by a team of education professionals, the courses were initially piloted over two semesters by 20 teachers in 12 school divisions and two First Nations education authorities; feedback from teachers and students was then incorporated in subsequent drafts of the curricula. The courses were also reviewed with input from Saskatchewan’s financial institutions and business leaders.

According to Nedelcov-Anderson, groups such as the Saskatchewan School Boards Association and the Saskatchewan Chamber of Commerce requested that the province develop the new courses, citing the need for greater financial literacy among young people. “Secondary students are making financial decisions every day,” she says, “and we want to ensure that Saskatchewan’s students have foundational skills and knowledge that will help them.”

Some of those same goals led Nebraska legislators in 2012 to create a state Financial Literacy Cash Fund (LB 269). Funded by an increase in the annual building renewal fee for payday lenders, the law directs the University of Nebraska to provide assistance to entities that offer financial literacy programs to K-12 students.

The Nebraska Council on Economic Education oversees use of the fund. Jennifer Davidson, the council’s president, says that while intake to the fund is small (about $55,000 at its peak, now about $42,000 annually), it has been an important tool in supporting five university-led centers across the state that help high school teachers incorporate or improve instruction on financial literacy. Last year, too, with the passage of LB 399, Nebraska began a review of the state’s social studies standards and curriculum, including instruction on financial literacy.

The new standards will take effect in Nebraska next school year, Davidson says, and will allow for “more focus on deeper topics, like investor education, the difference between saving and investing, career outlook and ensuring students have an opportunity to research what it means to invest in an education.” Nebraska’s Financial Literacy Cash Fund will allow teachers to take part in workshops and other programming that help them implement these new state standards, Davidson adds.

The 2020 Midwestern Legislative Conference Chairman’s Initiative of Michigan Sen. Ken Horn is on state policies to improve literacy.