New state policies emerge as jails and prisons become COVID-19 hot spots in parts of the Midwest

With the number of COVID-19 cases increasing, and a rise in deaths from the disease, “social distancing” has become a familiar term and way of life across the country. But how is social distancing possible for people whose days are spent in a 6-by-8-foot cell with another person? How can state and local governments maintain public safety while protecting inmates? How can they prevent outbreaks from starting in correctional facilities, and then spreading to the wider community?

These are some of the questions that have vexed criminal justice administrators, inmates, staff and family members for months.

These are some of the questions that have vexed criminal justice administrators, inmates, staff and family members for months.

“If you want to prevent the rapid spread and impacts of COVID, you have to look where it is,” says Professor Sharon Dolovich, who launched the UCLA School of Law’s COVID-19 Behind the Bars Data Project, which is tracking COVID-19 conditions in the nation’s correctional facilities. “Prisons and jails are where it is because of the conditions we have created and allowed to be perpetuated for all these decades.”

These facilities, she notes, are not insulated from their surrounding communities. Workers and food and supply deliverers are constantly cycling in and out, and even though many prisons have health clinics, they don’t have the capacity to deal with emergencies. Under these circumstances, residents with serious conditions such as COVID-19 are taken to local public hospitals.

Dolovich cites two other reasons why jails and prisons are so important to states’ COVID-19 response. First, governments have a moral and constitutional obligation to keep prison and jail residents alive and safe. Second, longer sentences and unsanitary conditions have created an older, more vulnerable population.

Early policy responses: End face-to-face visits, curb new admissions

Across the country, one of the common policy responses has been to eliminate inmates’ face-to-face visits with friends and family. Contact with the outside world, though, is integral to inmates’ mental health. One alternative for states and local governments: Eliminate inmates’ barriers to contact with family and friends in other ways, by waiving or reducing customary fees for phone or video calls.

Many states and localities, meanwhile, have tried to reduce jail admissions to keep COVID-19 out of their facilities. Between the first week of March and the first week of April, for example, daily jail bookings in Minnesota’s Ramsey County were down by about 74 percent.

A statewide stay-at-home order was one reason for this decline, the Star Tribune reported in April, but another was instructions to local police departments to reserve jail beds for violent offenders. Likewise, Chippewa County, Wis., reduced its jail intake by about 50 percent by issuing citations and court dates instead of arresting and holding offenders in pretrial detention.

Once a virus is inside a jail or prison, it is almost impossible to stop the spread. As of late April, 692 inmates and staff at Chicago’s Cook County Jail had tested positive for COVID-19; six detainees and a correctional officer had died. Around that same time, Ohio’s Pickaway Correctional Institution and Marion Correctional Institution had 1,609 and 2,165 confirmed cases, respectively. Eight Pickaway inmates had died; one inmate and two corrections officers at Marion had died.

Ohio leads on testing; other states helping inmates with health costs

These numbers from Ohio are eye-popping and concerning, Dolovich says, but the public knows about them because of Gov. Mike DeWine’s leadership in implementing a best practice that other states should follow: He ordered the testing of every prisoner at Marion, Pickaway and a third Ohio corrections facility.

“People ask, ‘What’s going wrong in Ohio that they have 2,000-plus cases?’ ” Dolovich says. “My answer to them is that everybody has prisons with 2,000 cases; we just don’t know which ones they are because no one is doing enough testing.”

COVID-19 also can have devastating effects on inmates’ finances. As the nonprofit, nonpartisan Prison Policy Initiative notes, state prison jobs for incarcerated individuals typically pay between 14 and 63 cents per hour. So even a seemingly small out-of-pocket co-pay for physician visits becomes extremely high for inmates.

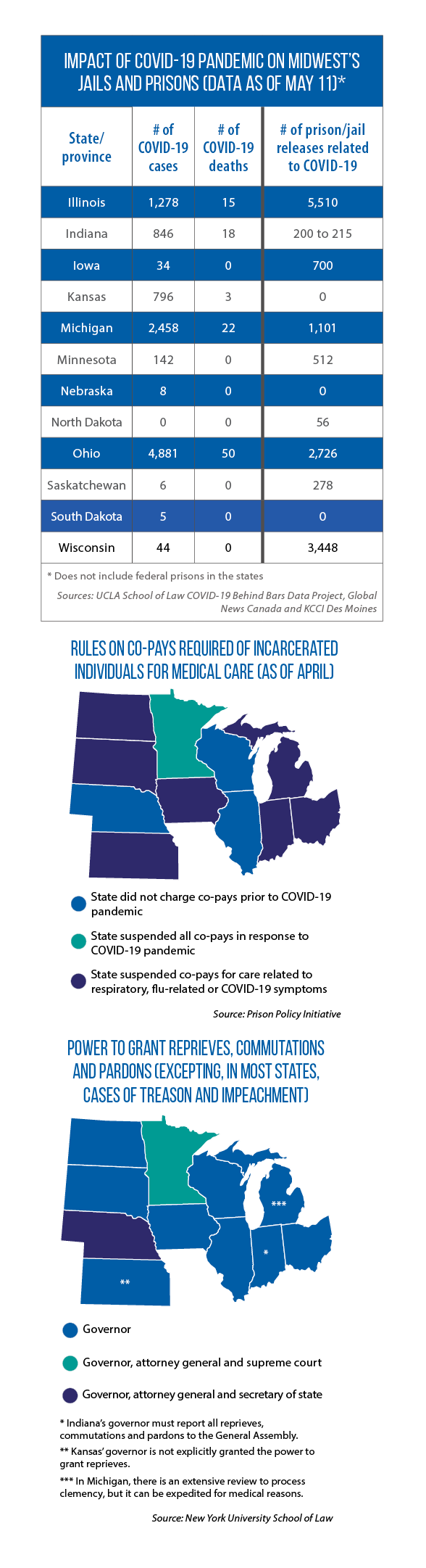

To help reduce this burden, states such as Minnesota have suspended all co-pays during the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic. As of April, Indiana and Kansas were among the states that suspended co-pays for medical care related to respiratory, flu and/or COVID-19 related symptoms (see map).

Governors commute sentences, expand release of prisoners for good behavior

The nonpartisan Brennan Center for Justice has urged the nation’s governors and other state policymakers to “release as many people as possible from incarceration, provided they do not pose serious public safety threats, for the duration of the pandemic.”

Its recommendations include commuting the sentences of older, more medically vulnerable inmates; expanding the use of “good time credit” programs; and keeping people who have been convicted of crimes, but not yet sentenced, out of prison for the duration of the health crisis.

In April, Gov. DeWine authorized the release of 105 Ohio inmates near the end of their sentences and commuted the sentences of seven others. Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker issued an executive order that eased some restrictions on early release for good behavior. (Pritzker also suspended admissions to all Department of Corrections facilities from the state’s county jails.)