‘Reawakening’ the border: A return to binational trade, movement is crucial to broader recovery

Even as the U.S.-Canada border shut down earlier this year to all but trade and the movement of essential workers, the strength and durability of the relationship between the two countries was on display.

“[They] worked as partners to restrict, but not [totally] close, the border,” Chris Sands, director of the Canada Institute at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, said during a May webinar for state and provincial legislators.

This cooperative effort (which included Mexico, via a separate border agreement with the United States), he said, was “historic.” And looking ahead, as the border begins to “reawaken,” he views the North American trading relationship as potentially more important than ever before.

According to Sands, one of the likely takeaways from the COVID-19 pandemic will be a push to change supply chains for essential goods such as medical equipment and supplies — away from producers in markets such as China to those in North America.

Not only will this be a deliberate policy shift among governments, he said, some manufacturers “will no longer want to put their supply chains at risk.”

He also predicts a general shift to “nearshoring”: Rather than expanding in far-off locations in the world with low-wage workers, manufacturers will invest in production facilities closer to home.

The webinar was hosted by The Council of State Governments’ Midwestern Legislative Conference Midwest-Canada Relations Committee, a 29-year-old group of state and provincial legislators that works to improve binational trade and relations.

The U.S.-Canada trading relationship has been the largest bilateral trading relationship in the world, with more than $2.4 billion worth of goods and services being exchanged each day before the pandemic. Cross-border movement has slowed considerably, but Sands discussed with lawmakers several “reawakening” steps for government to take as border restrictions are lifted.

As the border ‘reawakens’ …

At the federal level, Sands recommends “simplifying the border process by designating those companies that have invested in the security of their supply chains [by being approved by the United States’ and Canada’s trusted shipper or trucker programs] as essential.”

Such a move, he told legislators, will “allow for easier transit.”

As states and provinces move ahead with a reopening of their economies, he suggested that they think more regionally and look at eliminating unnecessary barriers — for example, a permit issued in one jurisdiction (whether it’s a state or province) should be recognized in the other.

Early on in the pandemic, much of the slowdown in trade activity was being caused by a decrease in demand rather than by the partial border closure. Factories that were essential parts of a cross-border supply chain have temporarily shut or slowed production to allow for physical distancing; and there has been an overall economic downturn due to pandemic-related job losses.

But Sands noted in the webinar that the bilateral relationship is much more than simply trading goods. Cross-border movement of all kinds, including tourism and shopping, “is so important for getting our economies moving again,” he said.

Because the two countries’ pandemic-related border rules allow only for trade and essential travel, tourism-dependent communities on both sides of the border — and many small and medium-sized businesses in the travel sector — have been severely impacted.

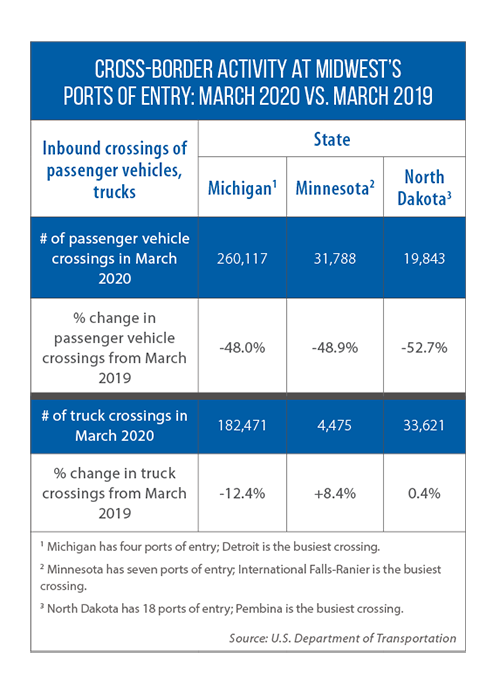

Recent data on passenger vehicle crossings in the Midwest underscore the big changes in travel that have occurred. In Michigan, Minnesota and North Dakota, the number of inbound crossings in March 2020 was only about half of what it was one year earlier (see table). Michigan’s decline has been slightly less, likely due to the relatively high number of health care and other “essential” workers crossing the border.

Problem solving: Who’s ‘essential’?

Exactly what makes for an “essential” worker was still being mulled in Canada and the United States, Sands said. As of early May, non-essential or discretionary travel included travel for tourism, recreation and entertainment.

Essential travel has been defined as including travel for supporting critical infrastructure, trade and commerce, and health security. Border officers still have some discretion, as do embassies when issuing visas, so some details were still being worked out. And problems in implementation were also being reported — for example, some technicians crossing to do repairs were being stopped at the border.

From the start of the pandemic, it was clear that essential workers would include health care professionals.

The Detroit metropolitan area relies heavily on nurses and other health care professionals from Canada to supplement its workforce. Estimates are that between 1,600 and 2,000 such workers cross the border from Windsor each day to work in or near Detroit.

This daily flow of health care workers is repeated throughout many communities along the border. With more than 1 million residents collectively in the cities of Detroit and Windsor, and more than 4 million in the Detroit metro area, this metropolitan area has the largest number of cross-border health care workers.

The Canadian government has resisted calls for these workers to choose one side of the border to work on during the pandemic. (Due to the large number of COVID-19 cases in the Detroit area, some Windsor hospitals have asked workers to make that choice.)

The U.S.-Canada relationship was also challenged when shipments of N-95 masks made by 3M and bound for Canada ran into a roadblock. Invoking the Defense Production Act, which presidents can use to expedite and expand the production of key goods in times of emergency, the Trump administration halted the export of these masks to Canada as well as to Latin America. (3M is the only U.S. supplier of N-95 masks to Canada, which does not produce them; the country does purchase masks from China.)

But following several days of discussions, the Trump administration exempted Canada and Mexico from this export ban on N-95 masks.

“Canada and the U.S. are close partners in the fight against COVID-19, and we are part of the shared supply chain for both PPE [personal protective equipment] and medical equipment,” says Joe Comartin, Canada’s consul general in Detroit. He notes that the supply chains for essential medical equipment (gloves, ventilators, testing kits, etc.) cross both ways, as do health care supplies, services and workers.