States have tools to help their farmers and rural businesses weather the COVID-19 storm

Name the commodity critical to the Midwest’s agricultural producers and rural communities, and evidence of the devastating, immediate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is plain to see.

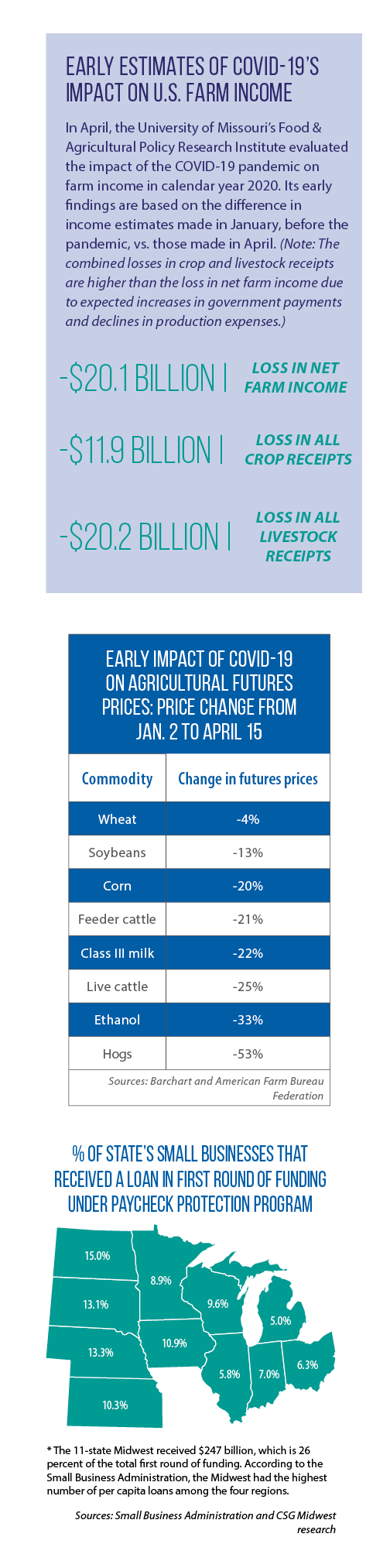

Futures prices for hogs and feeder cattle? Down 53 percent and 25 percent, respectively, between the start of this year and beginning of April, according to the American Farm Bureau Federation. Over that same time period, futures prices fell for ethanol (-33 percent), corn (-20 percent), soybeans (-13 percent), Class III milk (-22 percent) and wheat (-4 percent).

“We are definitely living in uncertain times, with every aspect of our economy affected,” Minnesota Rep. Paul Anderson said in April during a webinar hosted by The Council of State Governments’ Midwestern Legislative Conference Agriculture & Natural Resources Committee. “Agriculture has taken a big hit from the pandemic, and it will take many months, if not years, to recover.”

One of the takeaways from that webinar: State legislatures can play a central role in helping the Midwest’s farm operations and other rural businesses survive, and recover.

New disaster relief in Minnesota

Minnesota was one of the first states in the Midwest to take major legislative action in direct response to the COVID-19 pandemic, including the passage in late March of HF 4531. That bipartisan, $330 million measure covered a wide range of policy areas. To support farmers, lawmakers expanded the reach of Minnesota’s existing Disaster Recovery Loan Program.

That program originally was designed for farm-loss situations not covered by insurance — for example, replacing livestock or repairing septic systems and agricultural buildings. With the signing of HF 4531 into law, that state program will now cover losses of revenue due to “contagious animal disease” or “an infectious human disease for which the governor has declared a peacetime emergency.”

Those new statutory provisions will help producers get through market periods like these, when demand for agricultural products is down due to the closing of restaurants and schools and the overall drop in domestic and global economic activity. Along with the precipitous drop in commodity prices, producers have had to dump milk and euthanize hogs.

“A baseline of March 1 was set, and loans [are] available to cover the quantifiable loss of sales compared to that date,” Rep. Anderson, co-chair of the MLC Agriculture & Natural Resources Committee, explained to fellow legislators during the recent webinar. “An example for a dairy producer would be if the price of milk was $18 on March 1, 2020, and is now $12. That is a loss of $6 for every CWT of milk sold.”

The Legislature provided $3 million in direct appropriations to the Minnesota Rural Finance Authority’s revolving loan account for this program; the RFA also has the authority to sell $50 million in bonds to finance other ongoing initiatives, including help for beginning farmers and a seller-assisted loan program.

To apply for a Minnesota Disaster Recovery Loan, farmers work with their regular lenders. The RFA covers up to 45 percent of the loan, at an interest rate that is currently 0 percent. The remainder of the loan is paid back at the lender’s normal interest rate. As of late April, there was significant interest among agricultural producers in the program, but one requirement may have been slowing actual application filings — a farmer has to demonstrate his or her ability to repay the loan.

Because of current commodity prices, it is difficult for some farmers to show a positive cash flow. Some farmers may also be waiting to see what assistance they get from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Anderson said.

State programs connect rural businesses to private capital

One of the first legislative responses by the U.S. government was creation of the Paycheck Protection Program, or PPP. Many farm operations and rural businesses in the Midwest meet eligibility standards for this program, which is designed to help small businesses and workers.

While the availability of funding for the first round of PPP loans ran out quickly, this region fared better than others. For example, the Midwest led the nation in the percentage of states’ small businesses receiving these loans. Nationally, 5.7 percent of small businesses received PPP loans; in contrast, the rate in North Dakota was 15 percent (highest in the nation).

According to the U.S. Small Business Administration, one small bank in Nebraska ranked second in the nation for the number of PPP loans that it approved. And of the 10 U.S. states with the highest percentage of small businesses receiving funding under the first round of PPP, six were in the Midwest (see map).

Loans aren’t the only way to help rural firms and communities recover.

“State legislatures will play a critical and integral role in the recovery of their economies for rural small businesses,” Mark Scheffel, a former Colorado legislator and current senior vice president for Advantage Capital, said on the April webinar.

“Now is the time to plan for the deployment of much-needed capital for rural small businesses.”

One idea: Build on the New Markets Tax Credit program, a federal initiative created by the U.S. Congress in 2000. It provides tax credits for private-sector investments in businesses located in low-income, distressed communities (both rural and urban).

Some states have like-minded, successful programs of their own that have helped rural businesses gain access to capital and, as a result, add employees, Mackenzie Ledet, director of Stonehenge Capital, noted in the April webinar. Examples in the Midwest include Illinois’ New Markets Development Program, Ohio’s Rural Business Growth Program and Nebraska’s New Markets Job Growth Development Act.

“All of these programs can be easily tweaked to meet your state’s specific small-business needs in the COVID-19 recovery,” Ledet said to legislators.