COVID-19 contact tracing has states in Midwest launching new apps, hiring new workers and addressing privacy concerns

To keep people safe, stay ahead of COVID-19 infection rates, and allow for the continued loosening of “stay at home” restrictions, many states are trying to heed the advice of public health experts — ramp up contact tracing programs.

“There’s a real urgency in this … because we’re re-opening society,” says Dr. Marcus Plescia, chief medical officer for the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. “We’ve already seen new surges in COVID-19 cases.”

The idea is to isolate, or “box in,” the coronavirus so it can’t spread.

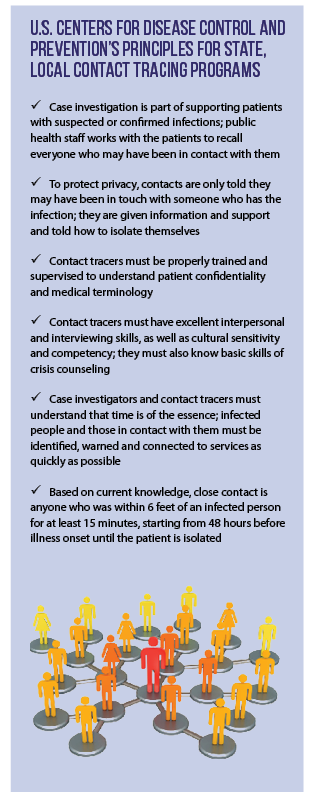

With contact tracing, local or state health departments track the movements of people who have tested positive for COVID-19 in order to find everyone who could have been exposed. Those exposed individuals are then contacted, tested and, if they test positive, put into isolation and treatment for 14 days before a retest.

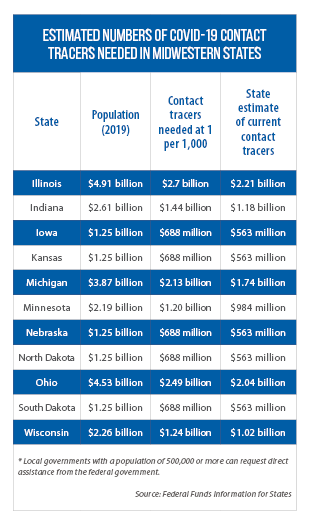

At least 100,000 contract tracers will be needed nationwide to provide effective tracing efforts, according to a study released in May by ASTHO.

“Because restarting society involves some risk of further COVID-19 infection and transmission, the ability of local and state health agencies to quickly identify, isolate, track and alert potential exposures and the capacity of the health care system to handle new cases or ‘surge’ is vital to any reopening plan,” the paper said.

Midwest states’ steps so far

Illinois’ budget (SB 264) appropriates $800 million for contact tracing and testing ($600 million of which comes from the state’s portion of federal funds via the CARES Act), while Michigan’s SB 151 includes $10 million in state funds for contact tracing in addition to the state’s share of federal funding for such efforts.

In Minnesota, in early June, legislators were working on HF 4579, which would establish a state contact tracing program and appropriate $300 million for it:

- $228 million to hire, train and employ tracers,

- $30 million each for technology and local health departments,

- $5 million for public education,

- $4 million to Native American nations for their contact tracing efforts, and

- $3 million for short-term employees to help launch the program.

Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers in May announced a $1 billion COVID-19 testing and contact tracing effort, to be paid for by federal CARES Act funds.

North Dakota’s Legislative Council in May approved a request from the Department of Health to boost its authority to spend federal funds by $5 million, in order to accept and spend federal grant funds for COVID-19 contact tracing costs. Those costs include case investigation, laboratory technicians, laboratory supplies and equipment. The state’s Emergency Commission, which consists of four legislators, the governor and the secretary of state, also approved the request.

(This commission may review and consider requests to accept federal funds during times when the legislature isn’t in session.)

North Dakota’s early use of tracking app

As of early June, North Dakota was the only Midwestern state to have launched an app for contact tracing. (South Dakota also uses it.)

People who download CARE19, released by the Fargo-based developer Proud Crowd, are given a random ID number; the app then anonymously stores location data throughout the day, tracking only locations where the person visits for at least 10 minutes. No personal information beyond the ID number and location data is kept.

“It’s a very powerful tool” that gives a tracer much more accurate information than hoping someone recalls their every step, says Vern Dosch, a 45-year veteran of the telecommunications and rural electric industries who was tapped by Gov. Doug Burgum to be North Dakota’s contact-tracing administrator.

“When you get the call that you’re positive and a contact tracer will be calling … it’s really hard to remember everywhere you’ve been in the last 14 days,” Dosch adds.

North Dakota will also offer a contact tracing app being developed jointly by Apple Inc. and Google’s parent company, Alphabet Inc., he adds. Once that happens, the new app will be called CARE19 Exposure while the existing app will be renamed as CARE19 Diary.

The province of Alberta, too, launched an app, ABTraceTogether. Information is stored for 21 days and is not shared without permission. Saskatchewan offers an online self-assessment tool to help people determine whether they should get tested for COVID-19.

New law in Kansas on privacy

An early version of North Dakota’s CARES19 was found to be sending the anonymous code and an “advertising identifier” to third parties, including Foursquare and Google. Although Foursquare said the app uses the free version of its software, which meant that information was discarded, Dosch says newer versions of the app addressed those privacy issues.

Concerns about that kind of information gathering recently led Kansas legislators to approve the “Contact Tracing Privacy Act” (part of HB 2016), at the request of Attorney General Derek Schmidt.

He proposed it in response to concerns raised after news reports suggested the Kansas Department of Health and Environment may have been using cell phone location data to track COVID-19. In addition, some residents of Linn County, Kan., filed a lawsuit over local contact tracing practices.

Under Kansas’ new law, participation in contact tracing must be voluntary and information cannot be collected through cell phone tracking (which seemingly excludes use of a CARES19-style app). Any information collected that way cannot be used by state agencies.

The act also requires that contact tracing information be kept confidential, and safely and securely destroyed when no longer needed. Collectible information will be determined by the Kansas secretary of health and environment “through the open and transparent process of adopting formal rules and regulations.”

“This new legislation does not address every question,” Schmidt said in a statement. “But at least this puts in place basic protections for civil liberties and privacy to replace the unregulated Wild West that otherwise was unfolding in COVID-19 contact tracing.”

The law runs through April 2021, giving legislators time to review how contact tracing should be regulated.

“[It] should give Kansans greater confidence that they are free to participate in contact tracing to help contain the spread of the virus, or not, as their best judgment may dictate,” Schmidt added.

Privacy concerns also are reflected in two pending Minnesota bills. SF 4500 would establish a contact tracing “Bill of Rights” making participation voluntary and information collected subject to the state’s existing privacy laws. HF 4665 would essentially ban mandatory, electronic contact tracing.

Jon Davis serves as staff liaison to the Midwestern Legislative Conference Health and Human Services Committee.