Utility shutoff moratoria serve a public health need in pandemic, but what will happen when they expire?

As the COVID-19 pandemic took hold and states and provinces began shutting down in March, many either required or called for halts on utility shutoffs due to non-payment of bills for the duration of the public health emergency.

But as economies reopen, questions arise: When should these state-imposed moratoria be lifted? What happens then?

“For people who are frail or in poor health, it’s a matter of life or death,” John Auerbach, president and CEO of the nonpartisan Trust for America’s Health, says about having access to water, heat and air conditioning.

“We’re really talking about what people need to survive.”

With residents being told to stay home by their governors, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urging hand-washing to deal with a highly contagious virus, all states took action earlier this year to prevent utility-service disruptions.

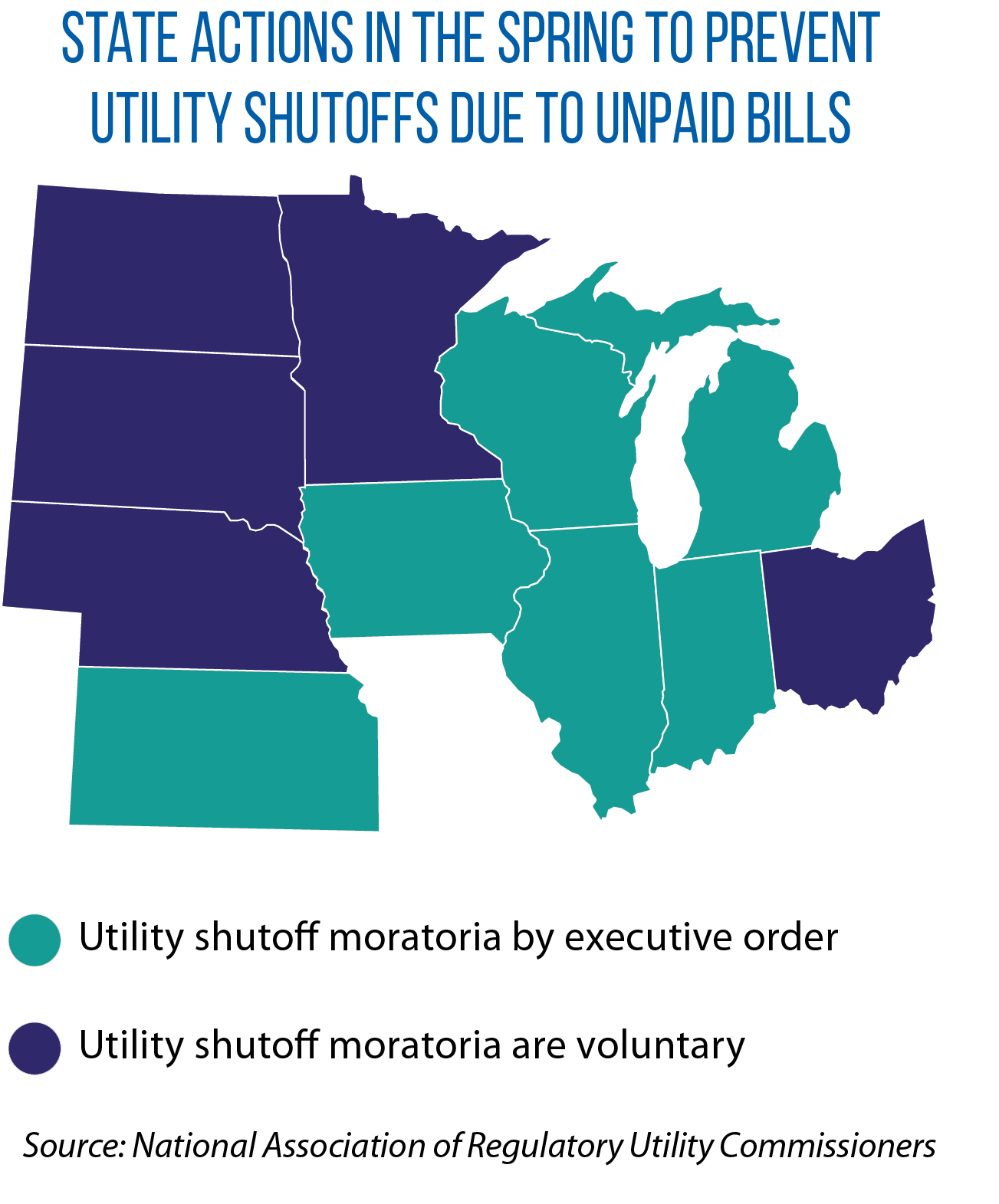

Moratoria were declared in 27 states, almost entirely within gubernatorial declarations of emergency, according to the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners. Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb’s executive order, for example, set a moratorium for the duration of the COVID-19 emergency.

Twenty-three states made such moratoria “voluntary” — asking utility companies to refrain from shutoffs during the pandemic, in much the same way that many already offer seasonal shutoff moratoria to avoid cutting off service in winter cold or summer heat.

But Wisconsin Rep. Beth Meyers, ranking member on the Assembly’s Energy and Utilities Committee, says she fears a new crisis as utility customers realize that their bill payments were deferred, not forgiven.

Her legislative colleagues, as well as officials from large utilities such as Xcel and small rural co-operatives, are beginning to ask how people will pay their utility bills once the moratoria are lifted. Her hope is that the Wisconsin Public Service Commission and the utilities find a way to help customers struggling with payments.

That happened in Illinois, where a relief plan negotiated by Attorney General Kwame Raoul, Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot, utilities and customer advocacy groups was announced in mid-June.

Whether there is a legislative role to be played, Meyers says, “I think that’s a good question and it’s something we’ll be looking into.”

Michigan has been using part of its federal CARES Act allocation to pay utility bills for low-income residents.

There, direct support payments are made to households that have past-due accounts of 90 days and that meet other eligibility requirements. The three largest utility providers, in turn, waive 25 percent of the outstanding bill for households receiving the direct payment. This allows for available Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program resources to assist more families.

In Saskatchewan, the interest on late bill payments was waived for up to six months. The province of Alberta allowed utility customers to defer electricity and natural gas payments until mid-June, while Manitoba Hydro suspended disconnections “until further notice” and late payments for six months.

According to Canadian Urban Sustainability Practitioners, all electric and gas utilities in Ontario suspended disconnections after talks with MPP Greg Rickford, who is the province’s minister of energy, northern development and mines.

Twenty-five years ago, a heat wave killed 739 people in Chicago who either didn’t have air conditioning or couldn’t afford to run it. That deadly summer in the Midwest’s largest city is an example of why utilities are crucial to maintain basic health, Auerbach says. And without water, people quickly develop basic survival issues from dehydration to poor sanitation, he adds.

Jon Davis is CSG Midwest staff liaison for the Midwest Legislative Conference Health & Human Services Committee.