After death of George Floyd, push for state-level change intensifies: Proposals seek new police training protocols and ways to prosecute misconduct cases

Eight minutes and 46 seconds. That’s how long Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin kneeled on George Floyd’s neck while three other officers stood by and watched as Floyd died.

Twenty rounds. That’s how many shots were fired by three Louisville, Ky., police officers into the home of Breonna Taylor as they executed a no-knock search warrant, killing her as she slept.

Twelve years old. That’s how old Tamir Rice was when he was shot and killed by a Cleveland police officer while holding a pellet gun in a public park.

This list can go on and on.

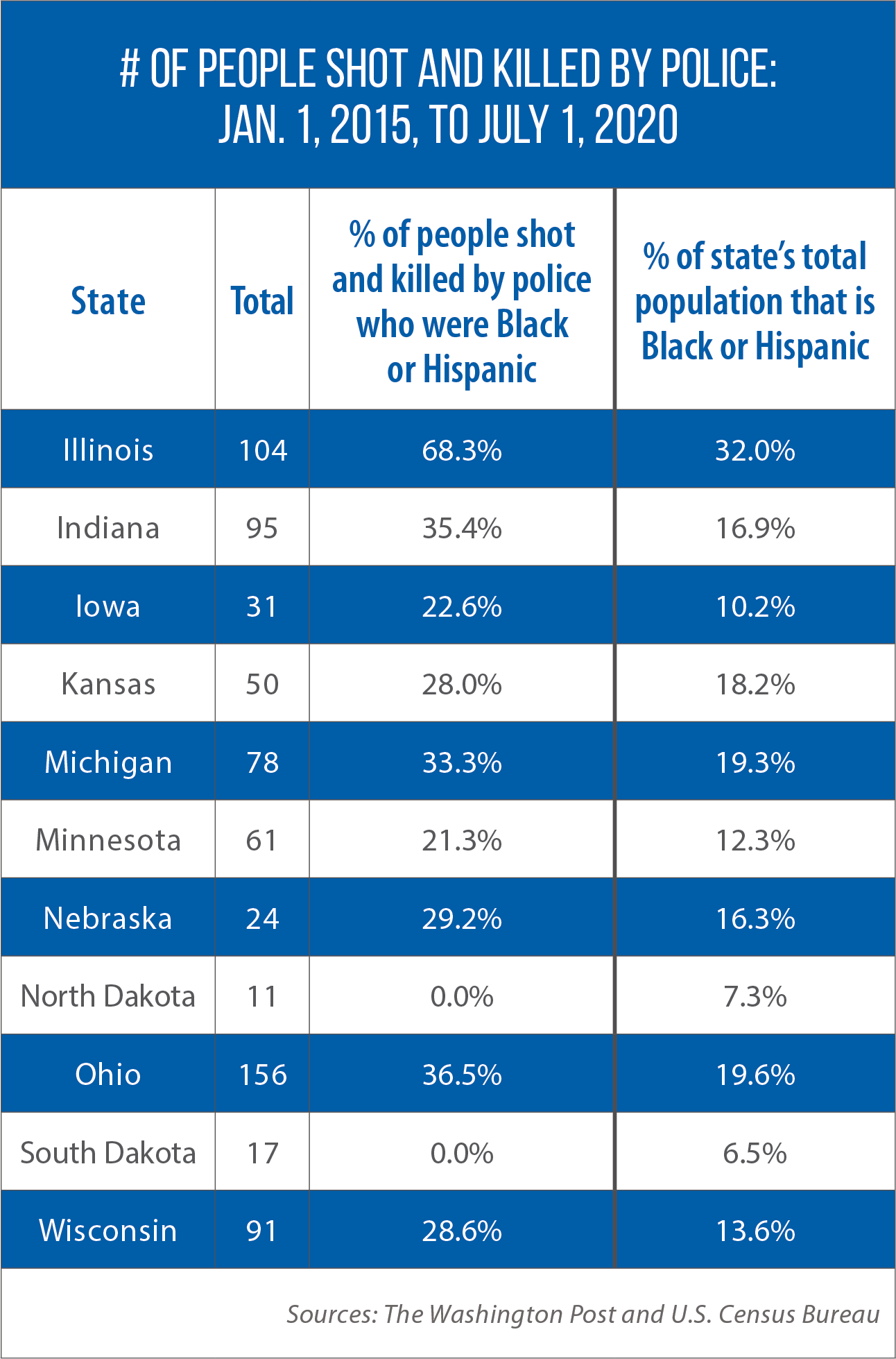

According to The Washington Post, 5,424 people have been shot and killed by police since Jan. 1, 2015. (See sidebar for state-by-state data for the Midwest.) African Americans make up 24 percent of those shot and killed by police; in 353 of these 1,298 incidents, the individual possessed neither a gun nor a knife. (African Americans make up 13.4 percent of the U.S. population.)

Following the death of George Floyd in late May, protesters took to the streets in all 50 states and in more than 60 countries.

Their calls for change have included a push for new state laws — for example, bans on chokeholds and certain other restraints, greater civilian oversight of police, and mandatory de-escalation training.

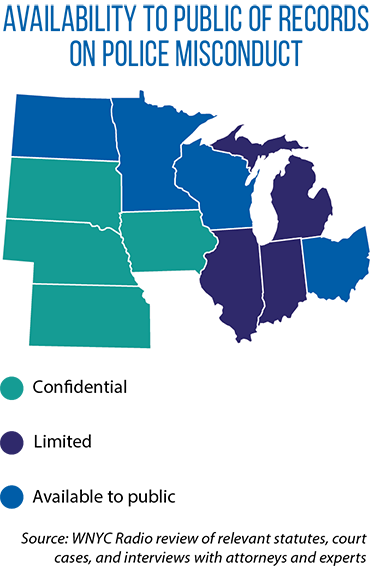

In New York, one of the first U.S. states to act following Floyd’s death, legislators repealed statutory language that had shielded police officer’s disciplinary records from public view.

“The death of Eric Garner [was] one of the many incidents that drove the reform,” says Weihua Li of The Marshall Project, a nonpartisan, nonprofit news organization that covers the U.S. criminal justice system.

After Garner’s officer-involved death in 2014, Li says, “it was impossible for his family to obtain disciplinary records of the officer who killed him — until those records were leaked.” That will change as the result of New York’s new law.

In the Midwest, legislation has been introduced in many state capitols since the May 25 death of George Floyd, including Minnesota. And in July, during its second special session of 2020, the Legislature passed HF 1. This comprehensive measure:

- bans the use of chokeholds, except when a peace officer or other’s life is endangered;

- prohibits “warrior” style training of officers;

- establishes an independent unit within the Bureau of Criminal Apprehension to investigate officers when they kill someone or are accused of sexual misconduct;

- adds two citizen members to the Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) Board; and

- changes the arbitration system for officers accused of misconduct.

A month earlier, Iowa became the first state in this region to get a comprehensive police-reform measure from introduction to enactment.

Iowa reforms adopted soon after Floyd’s death

Iowa reforms adopted soon after Floyd’s death

Going as far back as the Civil War, House Majority Leader Matt Windschitl says, Iowa has been a national leader in the fight for racial parity and justice. (His home state, for example, sent more citizens to fight in the Civil War, on a per capita basis, than any other state.)

“The times we are in now should be treated no differently,” he adds, “when we see injustices happening that should never happen in a civilized and equal society.”

This year’s response in Iowa was the passage of HF 2647.

The new law bans chokeholds by law enforcement, unless the officer “reasonably believes” that a suspect will use deadly force and can’t be apprehended in another way.

HF 2647 also authorizes the Iowa attorney general to prosecute officer-involved death cases; previously, the local county prosecutor had to request the attorney general’s participation.

Lastly, under this new Iowa law, police departments will not hire individuals previously convicted of a felony, and officers will receive annual training on de-escalation techniques and implicit bias.

Taken together, the bill’s sponsors say, these statutory revisions will help provide for meaningful change in policing.

How did the Iowa Legislature act so quickly, and in such a bipartisan fashion?

Windschitl credits communication, early and often, between the state’s legislative leaders.

“The first meeting the speaker of the House [Pat Grassley] and I had upon the Legislature reconvening was with the minority leader [Todd Prichard] and Rep. Ako Abdul-Samad, who is a leader in the African American community in our capital city,” he says.

“That meeting led to many subsequent meetings with leaders from both chambers and both parties, including Gov. [Kim] Reynolds, to come together and craft the justice-reform legislation.”

Much more work remains to be done, on policing and overall disparities in Iowa’s criminal justice system.

As of 2017, Black Iowans were being incarcerated at a rate 9.5 times higher than White Iowans, the second-highest rate of disparity in the Midwest.

Statistics like those led Gov. Reynolds to form a special statewide committee on criminal justice reform.

Its recommendations, released in 2019, focused on how to reduce rates of recidivism by expanding services to individuals while in prison (behavioral health, treatment, education, etc.) and strengthening re-entry programs (transportation and workforce development, for example).

“The conversations are ongoing and will take time to properly identify what the next steps are moving forward,” Windschitl says.

“Many times the best solutions can be found in our communities, and the way we look at and treat one another.”

Michigan House, Senate move bills on police training

Michigan House, Senate move bills on police training

Three days after the death of George Floyd, Michigan Sen. Jeff Irwin introduced SB 945, which would require all incoming police officers to complete training on implicit bias, de-escalation techniques, and the use of procedural justice in interactions with the public.

Additionally, the bill would require officers to complete 12 hours of continuing education annually. SB 945 passed the Michigan Senate in just one week. A near-identical measure, HB 5837, was passed by the House in June.

According to Irwin, the language of SB 945 had been circulating since last year, but after Floyd’s death and the public outrage that followed, many senators were clamoring for action. That led to the legislation’s quick introduction and passage.

But even if this measure on police training becomes law, Irwin says, it’s only a start.

“The four main categories I focus on are citizen oversight, independent investigations of police misconduct, demilitarization of police forces, and better training and accountability around [officers’] licenses and certification,” Irwin says.

Policing in the United States is quite dispersed, with several hundred city police departments and county sheriff offices in every state.

Still, Irwin says, state governments can help drive many of the necessary reforms.

“[We] have a tremendous role when it comes to certification and licensing,” he says. “I also think the state has a role in modeling best practices to our local governments.”

As one example in his home state, he points to the addition of public members to the Michigan Commission on Law Enforcement Standards as a best-practice model for increasing citizen oversight and police accountability. (This state commission handles the licensing, and license revocation, of officers.)

Value of independent investigations, prosecutions

Value of independent investigations, prosecutions

Months before George Floyd’s death, an 18-member working group in Minnesota (including two members of the Legislature) released 28 recommendations aimed at reducing deadly-force encounters with law enforcement. Among the ideas:

- Adopt use-of-force standards that make sanctity of life a core organization value and that include requirements for de-escalation, and

- Improve training and develop new models of response to de-escalate incidents involving individuals in a mental health crisis.

Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison, a co-chair of that working group, says Floyd’s death “tragically highlights the importance” of adopting those 28 recommendations — some of which were included in HF 1 from the July special session

“What happened to George Floyd is of course tragic for him and our community, but the reason that it was so massively explosive is that it has become a common occurrence, an appalling condition that we see all too often,” he says.

“The murder of Philando Castile [in Falcon Heights, a suburb of St. Paul] is fresh in my memory; Jamar Clark [in Minneapolis] as well; and many others.”

Ellison will be leading the prosecution of the officers involved in the Floyd case, at the invitation of Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman and at the request of Gov. Tim Walz.

“The only way to get compliance is to enforce the law; it is an indispensable part of the overall move to reform policing,” Ellison says.

“Yet it’s not sufficient.”

Ellison also suggests that legislators look at reducing the scope of qualified immunity (the doctrine that grants government officials, including police officers, immunity from civil lawsuits as long as they did not violate “clearly established” law) and establishing independent investigations for use-of-force cases involving police. The latter is included in HF 1, which establishes an independent unit within the Bureau of Criminal Apprehension to investigate officers when they kill someone or are accused of sexual misconduct.

“Make sure the investigation and prosecution are viewed to be independent and not based on any prior relationships that might lead people to believe there are some folks who are above the law,” Ellison says.

Within days after the death of George Floyd, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz asked another statewide, constitutional officer to lead prosecution of the case. Attorney General Keith Ellison agreed to take on this new responsibility, and soon after, he filed formal charges against the four Minneapolis police officers involved in Floyd’s death.

Within days after the death of George Floyd, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz asked another statewide, constitutional officer to lead prosecution of the case. Attorney General Keith Ellison agreed to take on this new responsibility, and soon after, he filed formal charges against the four Minneapolis police officers involved in Floyd’s death.

In a June interview with CSG Midwest, Ellison discussed his leadership role in this historic case, and moment in U.S. history. Here are excerpts.

Q: Why are you leading prosecution of the case, rather than the local county prosecutor (Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman)?

A: Well, the first thing that happened was Mike Freeman asked us to partner with him on the case, and Hennepin County is still very involved. We’re working together. The governor wanted us in publicly, and that was important to him. The way that the Minnesota attorney general can get into a criminal case is if we’re referred to by a county and invited in, or if we’re assigned by the governor. In this situation, both happened.

Q: For state legislators across the Midwest and country, what are some state-level policies that you would single out as ways to prevent deadly-force encounters among police and civilians?

A: I think it is a good idea to reduce the civil burdens to hold police accountable. Getting rid of, or modifying, qualified immunity is a very appropriate thing to do.

I think that it’s critical to have independent investigation and accountability by creating units within [government] to make sure the investigation and prosecution are viewed to be independent and not based on any prior relationships that might lead people to believe there are some folks who are above the law. People need to know that the outcome is based on the facts and the law.

Q: What are some of those “civil burdens” that you view as an obstacle to accountability?

A: With collective bargaining agreements, which are basically a labor contract between the city and the police union, if there is a dispute around misconduct, it goes to an arbitrator. That shouldn’t be.

I don’t have a problem with things like pay and pension and working conditions being bargained collectively, because I believe in unions. But when it comes to an officer engaging in misconduct, that should not be subject to arbitration. Those provisions should simply be void in the public interest. So that the chief can fire people and there can be a city council or a mayoral appeals process, but that you don’t go to a nameless, faceless arbitrator who just puts the person back on the force.

What you have now is a situation where somebody beats up a citizen, they’be been in trouble for it before. Meanwhile, the arbitrator just puts them right back on, in defiance of the chief.

Q: Months prior to the death of George Floyd, you helped lead a working group in Minnesota that released 28 recommendations on how to reduce deadly-force encounters. Which of those strike you as particularly relevant right now?

All 28 of them! The bottom line is, we need to do a whole range of things that make the system of safety and security more responsive and interactive with the community, and more accountable to the community. This starts with changing the POST [Peace Officer Standards and Training] Board conditions. People need to know about and engage with the POST Board.

It means that police departments need to engage in trauma-informed training. It means that mayors and city councils really need to adopt systems on what to do in the tragedy of an officer-involved shooting or death. Families lack information. They might have a loved one die, and nobody knows, and they never get any answers.

We do need to change our system of standards for uses of force. We do need a system that really says we have sanctity of life at the core of our policy, and that an officer might need to back off of someone if that person is not posing an immediate threat to others. Even if they may have a weapon or a knife does’t mean you go shoot them. Maybe it means you close the door of the room that they’re in, and call mental health people to say we’ve got somebody in a mental health crisis.

We need to use things like body cameras in a non-disciplinary way, meaning we need to use it to do training and assimilation and review.

I know that the public thinks that this is a finger snap, but this system has developed over the course of 350 years. This system of law enforcement has developed over long periods of time. It won’t just be fixed with officer training, and it won’t just be fixed with changes in legal accountability, or body cameras. We need all of this stuff — plus more.