COVID-19 pandemic strained usual interstate resource sharing during emergencies, but also underscored value of cross-border cooperation

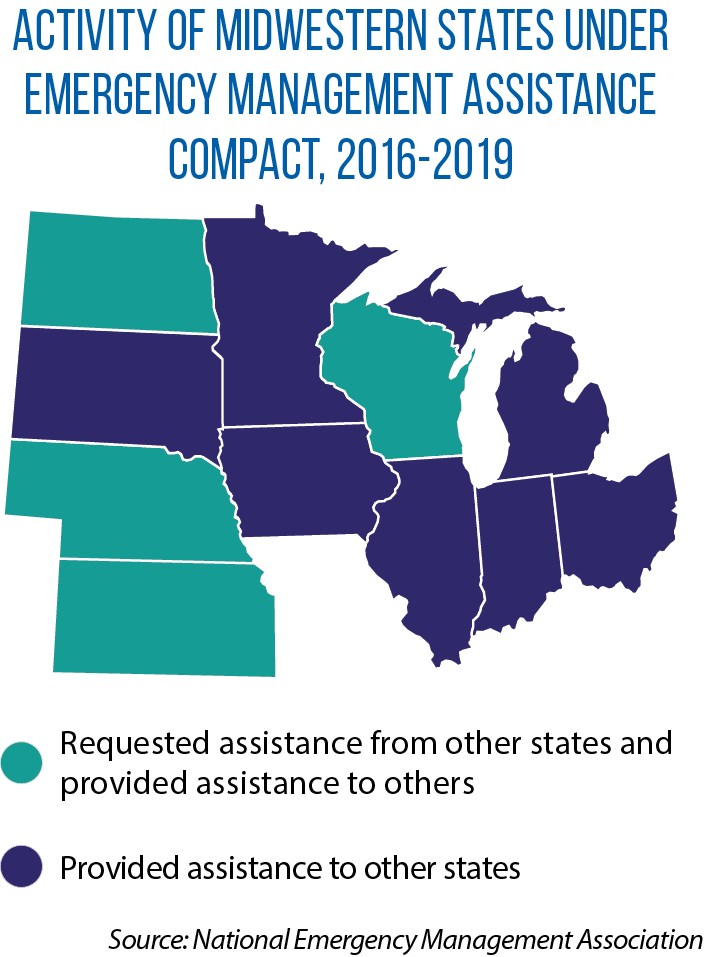

States are accustomed to working together and helping one another through times of crisis or natural disasters. Between 2016 and 2019 alone, via the congressionally authorized Emergency Management Assistance Compact, more than half of the U.S. states requested assistance from others. Every state but one provided help to another state during this time. In all, more than 29,000 personnel were deployed to states in need of help.

But the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 has brought challenges to states that they have not previously faced. That includes how to facilitate interstate cooperation and support.

Take, for instance, the deployment of health workers and others through EMAC, which offers license reciprocity and legal protections to personnel assisting from other states.

“We learned very quickly that during a national and global pandemic, and when the president for the first time ever declared a 50-state emergency, [a state’s] medical resources needed to be kept close to home,” says Trina Sheets, executive director of the National Emergency Management Association, which administers the disaster-relief compact and is an affiliate of The Council of State Governments.

That goes, too, for scarce resources such as ventilators, personal protective equipment and other medical supplies.

Still, states have come up with ways to work together during the COVID-19 pandemic, and as each jurisdiction looks to recover and be better prepared for the next public health crisis, one option is to pursue greater interstate, regional cooperation.

Telehealth support

EMAC is a mutual-aid agreement between the 50 states, the District of Columbia and U.S. territories. It covers all governor-declared disasters. Once a declaration is issued, other states can come to a state’s aid with personnel, equipment and supplies. State emergency management agencies are responsible for implementing the compact on behalf of their respective governors. The compact was ratified by the U.S. Congress in 1996 and was used extensively following the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

In early April of this year, EMAC was invoked to share medical resources in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and California provided lifesaving ventilators to Illinois and a handful of other states hard hit early on. (The ventilators are owned by California, and loaned through EMAC.) During that same period of time, two additional states shared personal protective equipment and a public health incident management team.

But as the virus spread, states realized they had to keep their medical resources and personnel close — for example a health care worker who traveled to a different state would have to be quarantined for 14 days upon his or her return home.

One alternative became increasing interstate cooperation in the area of telehealth. While EMAC always covered reciprocity for professional licensing, telehealth services had never before been a consideration. True to the nature of EMAC, however, it is possible to deploy these services through the compact. And during the pandemic, a draft executive order was shared with governors to allow medical professionals in good standing in another state to provide telehealth services using remote technologies within their scope of practice.

Several governors subsequently issued these executive orders. The result: Even if doctors, nurses or other health workers couldn’t travel, they could provide some assistance remotely for areas hit hard by the pandemic.

‘Beyond tunnel vision’

Some states also made moves to work together on the problem of securing personal protective equipment, medical supplies and testing equipment. Michigan and Ohio are part of a new six-state compact to ease shortages and delays for COVID-19 testing. The states immediately began working together to negotiate with manufacturers and to make bulk, joint purchases of point-of-care antigen tests.

In early May, the governors of seven Northeastern states (Connecticut, Delaware, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania and Rhode Island) signed an agreement to address these shortages and collaborate more broadly on their COVID-19 response.

They originally planned to focus on finding suppliers who could meet the demands of the time and combining orders to reduce costs. The governors hoped this would stabilize the supply chain by making demand more predictable. But as shortages for equipment and supplies began to ease in May, the focus of the regional agreement shifted — away from joint purchasing and toward a strategy for reopening states and their economies.

For example, if one state was reopening restaurants or beaches on a particular day and another state was doing so several days later, it might be better instead to do so on the same day, in order to avoid a crush of people at the same location. This kind of information sharing soon became critical for the Northeast states, says A.J. Schall, director of the Delaware Department of Emergency and the governor’s homeland security adviser.

Ultimately, the seven states formed three formal, interstate working groups — one for governors’ chiefs of staff, another addressing public health, and a third addressing emergency management and procurement. These groups meet weekly and allow states to share reopening efforts, discuss supply-chain problems, and plan for a likely uptick in COVID-19 cases in the fall.

“[Our] calls allow us to get together with peers and make sure we move beyond tunnel vision and think through problems together,” Schall says.

While the creation of a joint-purchasing program will be discussed in more detail, the Northeastern states decided that it was more important to first share information on state contracts with suppliers and on trusted vendors. In the event of another public health emergency, these states can then shorten the vetting process for vendors and move forward more quickly on purchasing.

According to Sheets, one lasting lesson of the COVID-19 pandemic is the need for states themselves to ensure they have an adequate stockpile of medical equipment, supplies and other items. That will take additional funding, she says, but states cannot rely on the Strategic National Stockpile to meet all of their needs. Sheets suggests three other ways for states to strengthen their responses to future disasters and emergencies.

- Review the requirements, limitations and procedures for the waiver or suspension of laws and regulations during public health emergencies.

- Consider a statutory requirement that state governments and individual agencies have plans for continuity of government and continuity of operations. Along with this law, she recommends that states conduct annual training and exercises on these plans.

- Determine whether legislation is needed to address liability issues associated with having the private sector, nonprofit organizations and volunteers become mutual-aid resources. This kind of law would help facilitate disaster and recovery responses within a state, as well as in other states through EMAC. States may need enabling legislation or a memorandum of understanding in place to make individuals in the private sector or in a nonprofit “agents of the state.” Such a designation would allow states to assume liability for these individuals, who then can be deployed through the disaster-relief compact.

Binational rebound

In times of emergency or disaster, states and provinces also work together, through agreements such as the Northern Emergency Assistance Compact. NEMAC currently has nine members: the states of Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota and Wisconsin, and the provinces of Manitoba, Ontario and Saskatchewan.

“Through NEMAC, we are able to work with Canadian provinces and support requests that don’t get to the level of a declaration of emergency or disaster from the governor,” explains Jake Ganieany of Montana’s Department of Military Affairs, Disaster & Emergency Services. Examples include ambulance shortages, medical emergencies, chemical spills or localized natural disasters.

Among the many ties that bind Canada and the United States is the strength of their cross-border economic relationship, which took a severe hit as the result of COVID-19. (Starting in March, the border was closed to all but essential workers and trade.)

Organizations are now working to support a cross-border, post-pandemic economy. One of them is the Canadian American Business Council, whose “North American Rebound” plan envisions a binational, collaborative manufacturing response that secures the availability of personal protective equipment for both countries and replenishes and maintains strategic stockpiles of medical equipment.

“There is an instinct to turn inward and look toward self-sufficiency and reshoring” after a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic, says Maryscott Greenwood, the council’s chief executive officer. But because the two countries’ economies are closely tied together, including supply chains that have products crossing the border multiple times before completion, a go-it-alone strategy is “probably impossible to do with the U.S. and Canada, and many companies know this,” Greenwood adds.

Several leading businesses and organizations in the Midwest have signed on to the “North American Rebound” plan, including the Illinois Chamber of Commerce. Laura Ortega, executive director of the chamber’s International Business Council, notes that trade with Canada is important not just to large companies, but to many smaller firms in her state.

Building partnerships between companies, including those across the border, is one way to help smaller companies expand their capacity and increase economic activity after the pandemic, she adds.