States taking steps to contain COVID-19 in nursing homes, other long-term-care facilities

As the COVID-19 pandemic grinds on, one trend has become clear and consistent: the virus is more deadly if introduced and spread in adult long-term-care facilities, which are accounting for a smaller percentage of cases, but almost half of all deaths nationwide since early May, according to an issue brief published in September by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

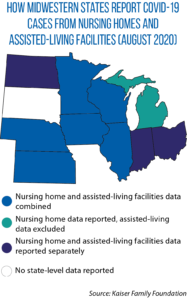

Kaiser’s analysis of data from 38 states (including all Midwestern states except South Dakota, which does not report cases or deaths in long-term-care facilities) found:

- Cumulative COVID-19 cases and deaths in such facilities rose from 50,000 and 10,000, respectively, in mid-April to 400,000 and 70,000, respectively, in mid-August.

- Nationwide, these facilities accounted for 18 percent of all cases in early May but just 10 percent by mid-August.

- Their share of total COVID-19 deaths nationwide fluctuated between 45 percent and 49 percent over the same period.

- The number of new cases and deaths in these facilities peaked in April, then decreased in May and June before cases began rising again in July (deaths began rising again in August).

Developing and implementing COVID-19 testing and containment strategies for nursing homes and long-term-care facilities were part and parcel of states’ initial responses to the pandemic.

Minnesota’s 5-point plan provides a response road map

But, as officials from the Minnesota Department of Health told legislators during an August 26 virtual meeting of the Midwestern Legislative Conference’s Health & Human Services Committee, those strategies are complicated by the fact that these facilities’ populations are older residents — many of whom have more underlying medical conditions than the general population — living in close proximity to each other and staff (who circulate outside the facility more often).

And that’s in addition to the industry’s pre-existing problems with finding and retaining trained staff, said Lindsey Krueger, director of the Minnesota department’s Office of Health Facility Complaints.

She and two of her colleagues, health policy director Diane Rydrych and senior epidemiologist Karen Martin, detailed Minnesota’s “Five-Point Plan to Protect our Most Vulnerable”:

- Expanding testing for residents and workers in long-term-care facilities;

- providing testing support and troubleshooting to more quickly remove barriers to effective testing;

- getting personal protective equipment to facilities when and where needed;

- ensuring adequate staffing levels for even the hardest-hit facilities; and

- leveraging partnerships with local and regional health care partners to better apply their skills and talents where needed most.

The department holds weekly briefing calls to share the latest updates and guidance, Krueger said.

As of mid-August, she told the MLC committee, residents of long-term-care facilities accounted for less than 1 percent of Minnesota’s total population and 7 percent of its diagnosed COVID-19 cases — and 74 percent of COVID-19 deaths.

Nor was COVID-19 striking all of the state’s facilities equally — only six in 10 nursing homes and three in 10 assisted-living facilities have ever had cases, with most of those having reported just one or two cases, she added.

“We feel one big factor in these numbers is space,” Krueger said. “Assisted-living residents have their own space without shared rooms or bathrooms. They also may need less assistance from staff for their activities of daily living, among other factors.”

Rydrych said adequate staffing was a pre-pandemic problem that complicated the response to COVID-19. Many facility managers indicated concern that if someone tested positive, they might not be able to get enough people to come in for work, and “that was leading some of [the facilities] to avoid doing testing they might otherwise need or want to do,” she added.

That was also driving when testing was done, Rydrych said. Certain days of the week presented bigger challenges to finding employees willing to come in to work, so a “lab tech database” of people willing to work in nursing home or long-term-care settings was established. Facilities short on staff could then use this database to find people, she added.

Facilities are required to have a staffing plan to anticipate shortages, and state employees act as a last line of sorts, able to step into emergency situations if no local employees can be found, Rydrych said.

Rydrych added that when a COVID-19 case is confirmed, a response team moves in to help with infection prevention, case interviews and contact tracing. In addition, each facility with an outbreak is assigned a Minnesota Department of Health case manager.

Rydrych said the state measures success in several ways: how well facilities maintain low numbers of positive cases after an outbreak begins in a long-term-care facility, reductions in the proportion of positive tests in affected facilities, and the support provided to them for on-site infection prevention.

Health officials in Minnesota are looking at broader measures of success as well. For example, do all skilled nursing facilities have updated COVID-19 preparedness plans? Are they able to get additional staff support without having to transfer residents to other sites for care? Has there been a decrease in regulatory infection-control citations? Are testing rates for COVID-19 at acceptable levels?

You can see their presentation here (beginning at 44:00).

Other states ramp up testing, preparation for ‘second wave’

In June, Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer issued an executive order establishing the Michigan Nursing Homes COVID-19 Preparedness Task Force. It includes directors of the departments of Health and Human Services and of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs, legislators (two from each chamber, including one from each party) and others.

This ad hoc panel was charged with helping prepare the state for “a potential second wave” of COVID-19 by meeting with state agencies and industry stakeholders, analyzing “relevant data on the threat of COVID-19 in nursing homes,” making that information publicly available, and making recommendations for improving the quality of that data.

Its final report, issued at the end of August, includes 28 recommendations on the availability of resources, quality of life for facility residents, staffing, and placement of residents including:

- Improving the coordination, distribution, allocation and/or procurement of personal protective equipment and testing supplies;

- dedicating labs and securing funding for continuing testing of nursing home residents; and

- improving support for the physical and mental health of facility staff.

Thirteen recommendations address residents’ quality of life, including allowing outdoor visits, limited communal dining and certain small-group activities; and “opt-ins” for residents to participate in indoor visits, and to establish “pods” with fellow residents.

In August, Ohio launched a mandatory statewide testing initiative for more than 765 assisted-living facilities that offers baseline saliva testing to all staff and residents at no cost to the facilities.

Indiana created “strike teams” in April to assist with testing if there is a cluster of cases at facilities where there are many essential workers.