Nebraska bans ‘surprise billing’ for emergency medical care; other states may do so, too

Nebraska in July became the latest Midwestern state to regulate “surprise billing” when the “Out-of-Network Emergency Medical Care Act” (LB 997) was signed into law.

Once it takes effect on Jan. 1, the law requires out-of-network providers to bill a patient for no more than his or her health insurance plan’s in-network co-payments, co-insurance or deductible for emergency care. It defines an emergency as the sudden onset of a medical condition that would place a person in serious jeopardy if not treated immediately, and limits a patient’s expenses to what would have been charged if the patient had been treated at an in-network facility.

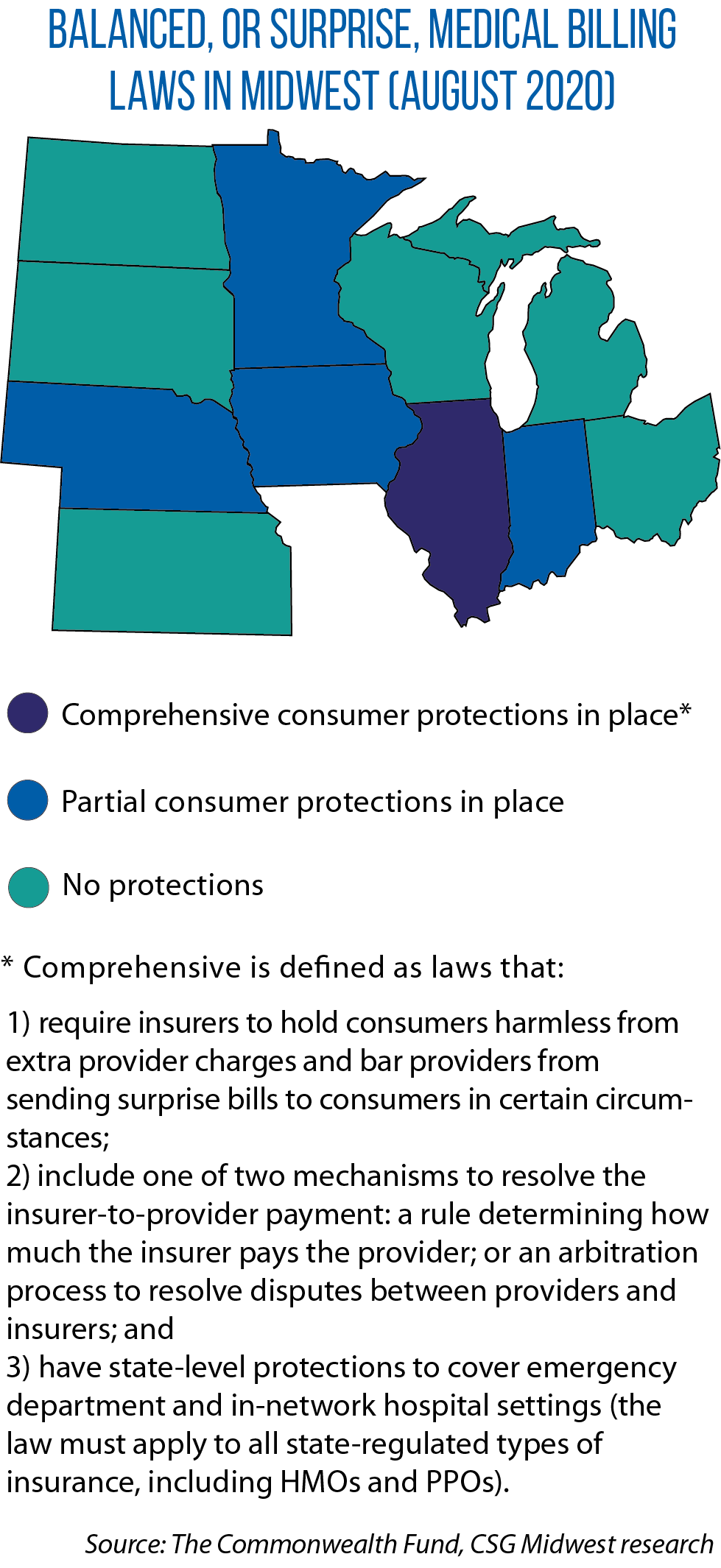

Nebraska joins Illinois, Indiana, Iowa and Minnesota in regulating surprise billing, which can happen when someone gets emergency care at an out-of-network facility or from an out-of-network provider, or when a person gets care at an in-network facility but is treated by an out-of-network provider.

Since the insurer doesn’t have a contract with the out-of-network facility or provider, it may decide not to pay the entire bill. In that case, the out-of-network facility or provider might then bill the patient for the balance, according to The Commonwealth Fund, a nonpartisan group promoting a better health care system that tracks this issue nationwide.

“We’re seeing more states working to adopt protections,” says Maanasa Kona, a professor at the Center on Health Insurance Reforms in Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute.

“There’s a lot of bipartisan interest in this; the real dividing line is between providers and insurers,” she says.

LB 997’s author, Sen. Adam Morfeld, says constituents raised the issue with him last year. One, a student, had an emergency yet was able to find an in-network hospital. Even so, he says she got surprise billing charges. After helping get that billing straightened out, “I did more research and realized it’s a fairly common phenomenon,” Morfeld adds.

He introduced LB 569 in the 2019 session, which would have banned surprise billing in emergency and nonemergency situations. The bill did not advance, but that summer, he and Sen. Matt Williams (chair of the Unicameral Legislature’s Banking, Commerce and Insurance Committee) convened a group of insurers and providers to find common ground, and decided to focus LB 997 on surprise billing only in emergency contexts.

In other Midwestern states, a package of bills (SB 570-573) to regulate surprise billing and provide penalties for violations is pending in Michigan. Kansas legislators this year mulled but didn’t pass surprise billing protections (SB 357).

A Wisconsin law (AB 1038) bans surprise billing for COVID-19 treatments. An Ohio bill (HB 579) would do likewise, including for future immunizations.

The federal CARES Act offers some surprise billing protection via the $175 billion Provider Relief Fund for medical providers responding to COVID-19. Those taking money from the fund can’t seek to collect out-of-pocket payments “that are greater than what the patient would have otherwise been required to pay if the care had been provided by an in-network provider.”

“A significant number of providers have accepted money from that fund,” Kona says.

Jon Davis serves as staff liaison to the Midwestern Legislative Conference Health and Human Services Committee.