Lesson in resiliency: How states, farmers and processors managed impact of COVID-19 on food production

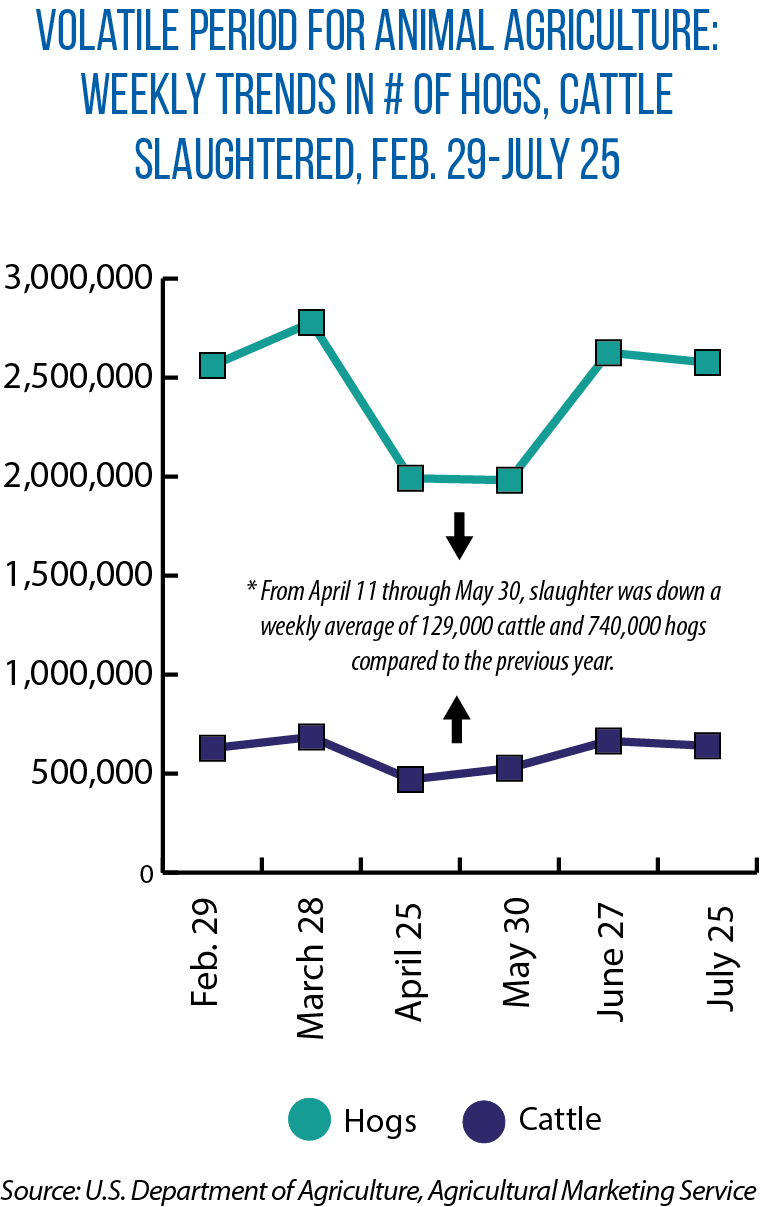

Just a few months ago, all signs pointed to an economic crisis in the nation’s animal agriculture industry due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Meat processing plants were being closed, or operations greatly curtailed, due to health concerns and illnesses among employees. By late April, nearly 40 percent of U.S. processing capacity was idle. Livestock slaughter plummeted (see graphic).

In the meantime, prices were falling for producers, who were also forced to hold livestock longer or euthanize slaughter-ready animals. While most cattle could be slowed down and held a little longer, the situation was disastrous for hog and poultry producers. For the eight weeks from April 11 through May 30, there were 22,000 cattle and 125,000 hogs per day ready for processing with nowhere to go.

“We faced a real disaster, and challenges remain, but the impressive way state officials, farmers and producer organizations have worked together to address the COVID-19 crisis is making a big difference,” says Cody McKinley of the National Pork Producers Council.

He and others credit the spirit of partnership, creative thinking and communication for helping the agricultural sector weather the storm. In April, some analysts were predicting that up to 2 million hogs would need to be euthanized; the number turned out to be much less.

Iowa Secretary of Agriculture Mike Naig praises livestock producers for “going to extraordinary lengths to find other markets and to donate to food banks,” but the states played a role as well. For example, Naig oversaw a Resource Coordination Center in Iowa to help farmers make informed decisions, and he teamed up with other state agriculture leaders, along with producers and industry organizations, to share information and develop creative alternatives.

One solution was to turn to land-grant universities for the processing of hogs for sale or donation. In South Dakota, Lt. Gov. Larry Rhoden says, the state partnered with South Dakota State University to move animals to the school’s meat lab for processing (despite most student labor having gone home). Labs at universities in states such as Iowa, Minnesota and Nebraska also were used to process animals for consumers and food banks.

Meanwhile, new collaborative initiatives between states and pork producer councils helped connect processors, farmers and food pantries — for example, “Pass the Pork” in Iowa, “Pork Cares” in Nebraska, and “Passion for Pork” in Wisconsin.

With help from industry and agriculture departments, producers were able to make contact with smaller processors all over the country. For example, hogs and cattle sometimes moved from the Midwest to smaller processors on both coasts. State departments of transportation assisted by increasing weight limits to get animals moved quickly and efficiently.

Across the Midwest, too, privately owned processing plants added hours and stepped up operations. Minnesota was one of the first states to help smaller processors increase capacity, via a grant program run through the Department of Agriculture.

“[It] awarded more than $200,000 to 46 state-inspected and custom-exempt meat processing plants to help them increase capacity,” Minnesota Rep. Paul Anderson explains.

In addition, states such as North Dakota, Kansas and Iowa have used money from the federal CARES Act to develop new grant or cost-share programs for small meat processing facilities, food processors, food banks and/or others. Another policy strategy has been to provide direct support for farmers impacted by the pandemic.

- In Iowa, up to $2,000 per farmer is available to help with the transition to direct-to-consumer sales.

- The Wisconsin Farm Support Program distributed $50 million in direct payments to farmers affected by the pandemic, with more than 12,000 farmers receiving payments.

- The Iowa Economic Development Authority allocated $60 million to livestock producers impacted by the pandemic (the maximum amount for a single producer is $10,000).

- Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Alberta each teamed up with the Canadian federal government to offer about $12 million per province to cover a farm’s cost of keeping animals longer. The provinces also helped farmers with the premium costs for Canada’s livestock risk-management insurance.

Even with all of these efforts, some animals had to be euthanized. Indiana and Minnesota established cooperative disposal sites, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service provided approximately $100 per animal unit.

Iowa paid farmers ($40 per hog and 25 cents per laying hen) forced to euthanize animals due to lack of market access. “The disposal assistance program is just one way the state is trying to help producers through this very difficult time,” Naig adds.

One takeaway from the experience of the last few months: The ability of state officials, producers and industry organizations across the region to communicate and work together is invaluable, a lesson to remember when future animal disease outbreaks or disasters occur.