Disaster recovery in Midwest’s agriculture communities requires state-led collaborations and interventions

As if the pandemic, trade wars and drought weren’t making 2020 tough enough on Midwest agriculture, a derecho swept from South Dakota to Ohio in August, traveling 770 miles in 14 hours. Winds in excess of 100 mph destroyed millions of acres of cropland and wiped out buildings and grain storage facilities.

“Derecho events are a very Midwestern phenomenon,” according to Scott Collis, an

Argonne National Laboratory atmospheric scientist. So much so, in fact, that they were first discovered and named in Iowa, in 1888, to describe an organized thunderstorm that can generate straight-line winds, hail, torrential rain and tornadoes.

Collis was one of three featured speakers during a September webinar of the Midwestern Legislative Conference Agriculture & Natural Resources Committee on how states can help rural communities recover from natural disasters.

“The derecho that traveled across the Midwest in August really highlighted

how damaging these events can be to agriculture,” Collis said, adding that the

region should “expect these storms to be more common [in the future].”

In Iowa, the most intense path of the storm plowed through 4 million acres of

corn (25 percent of the state’s total corn crop) and 2.5 million acres of soybeans.

“For the most part, beans stood back up, but corn is still lying flat,” Iowa Secretary

of Agriculture Mike Naig said on the September webinar.

According to Naig, the effects of storm events such as this one underscore the

importance of collaborations among government officials, farmers and farm

groups, and agribusinesses.

The state of Iowa is now working with the U.S. Department of Agriculture to

ensure that different insurance adjusters are consistent in how they assess damage

in the fields. Officials are also seeking federal assistance for the damage done

to grain elevators. Meanwhile, the state is using dollars from conservation programs to help with cover crops and replace wrecked windbreaks.

Another component to rural disaster recovery is a state’s university system and

extension services, including the role these institutions play in disseminating scientific and other information. For example, the University of Minnesota has created customizable forms for farmers to establish contingency plans for their operations.

Naig adds that in Iowa and other states, universities and extension services

coordinate assistance for farmers experiencing “mental and financial

stress.”

Natural disasters are becoming more frequent and severe; for agriculture, these trends reaffirm the importance of crop and property insurance. Insurance alone doesn’t ensure recovery.

States are expected to help financially and to assist with mitigation. When it comes to disaster-related spending, states should carefully track expenditures across all agencies and disaster phases Anne Stauffer of The Pew Charitable Trusts said.

The state of Ohio is doing just that through a joint system created by budget and emergency management officials. Their goal: Have the data needed to carefully review budget expenditures, and then adjust policies and budget outlays when needed.

Stauffer also recommended that states invest more in disaster mitigation. “Every

mitigation dollar spent has been shown to save an average of $6 in post-disaster

recovery costs,” she said.

The importance of federal aid also cannot be overlooked. This assistance has long been relied on by states, communities and individuals. But as disaster-related

costs rise nationwide, will state and local communities have to take on greater

financial responsibilities?

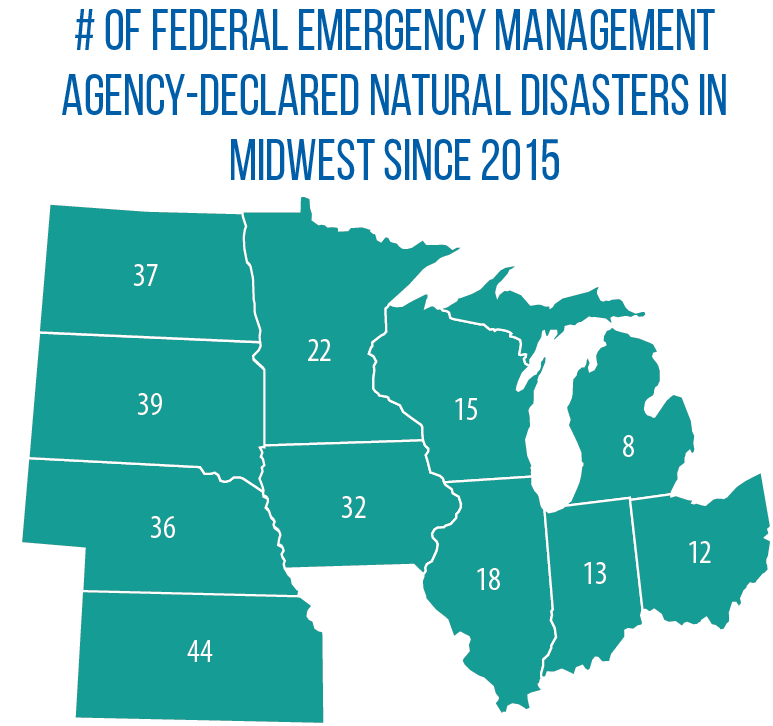

The Federal Emergency Management Agency has proposed raising the per

capita indicator, the damage threshold that determines whether a disaster warrants federal funding. In addition, disaster-related grants based on population can put rural, sparsely populated communities at a disadvantage. These same

communities are also less likely to have disaster-recovery expertise.

Rural communities, then, must continue to rely on each other. Recovery

is contingent on relationships among individuals, government institutions and nonprofit groups.