November 2020 Question of the Month | Counting mail-in ballots

Under state laws in the Midwest, when can election officials start verifying, processing and counting mail-in/absentee ballots?

Answer: This year, more than 100 million Americans voted before Election Day — a record number that was close to 74 percent of the total votes cast in the 2016 election, according to the U.S. Elections Project. In the Midwest, in every state, early-voting figures eclipsed 50 percent of total turnout four years ago. These statistics underscore just how different this year’s election was for voters, as well as state and local officials: For health and safety reasons, growing numbers of people chose to vote before Election Day, either in person or by mail.

These increases, especially in vote-by-mail, have raised questions about state laws that limit when ballots can start being processed and counted. Such statutory restrictions have been in place for many decades due to concerns that results could be released prior to polls being closed on Election Day, Amber McReynolds, CEO of the National Vote at Home Institute, said in an interview earlier this year with CSG Midwest. “Back in the day when it was more hand tallies and not optical scanners doing the tabulating, there was more of the potential of that happening,” she said.

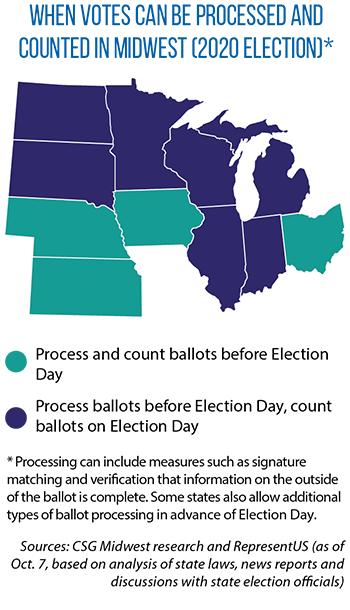

In the Midwest, with the exceptions of Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska and Ohio (see map), states don’t allow ballot counting to begin until Election Day, sometimes only after polls close. Outside the region, some states allow for ballot counting well in advance of Election Day — 15 days in Colorado and seven days in Oregon. These states have traditionally relied on mail-in ballot systems. California passed legislation this year that permitted ballot counting 29 days in advance of the November 2020 election.

Prior to counting, each ballot that arrives by mail must be verified. The ballot envelope typically contains information necessary to verify the voter, so election officials are able to match the name and address of a registered voter with the identifying information on the outside envelope, or the privacy sleeve, holding the mail ballot. Many states verify the signatures of the voter. Some states then allow further processing in advance of Election Day, such as removing the ballot from the envelope and unfolding it, or placing it in a sealed container for counting.

During the 2020 presidential primaries, more than half a million mail ballots were rejected. The most common mistake was related to voter signatures. Either a voter’s signature does not match the one on file, or the ballot envelope simply was not signed. According to the Campaign Legal Center, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 18 states — including Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota and Ohio — had required election officials to notify voters of an error that would cause a ballot to be rejected. These notice-and-cure provisions give voters a chance to fix their ballot, either by affidavit or in person. Other states adopted such laws this year in response to the rise in mail-in-voting. Some states also have faced court orders to allow voters to fix their ballots.

Question of the Month highlights an inquiry sent to the CSG Midwest Information Help Line, an information-request service for legislators and other state and provincial officials from the region.