On the frontlines of vaccination

From public awareness campaigns, to storage and distribution, to funding, states will play a leading role in efforts to control COVID-19 in 2021

States have at least two critical jobs in the months ahead regarding the COVID-19 vaccines. First, execute their role on the frontlines of distribution. Second, convince leery citizens to get vaccinated.

“That is, at this point, the most critical [element],” Michael Osterholm, a leading national voice on COVID-19 policy, says of public education and persuasion.

“It’s going to take a coordinated and comprehensive federal, state and local program that will, by necessity, involve the private sector.”

For much of 2020, states were preparing their vaccination distribution plans (they are available on The Council of State Governments’ COVID-19 resource page), based on plans from a decade ago for the H1N1 virus, as well as federal guidance.

Implementing, Paying for vaccination plans

What should a state vaccine distribution plan include?

Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research at the University of Minnesota and a member of President-elect Joe Biden’s COVID-19 Advisory Board, points to three key componens:

- tracking doses from federal sources via state distribution systems into patients’ arms;

- a system to store, distribute and administer the vaccine; and

- a program to educate and convince people to get the vaccine.

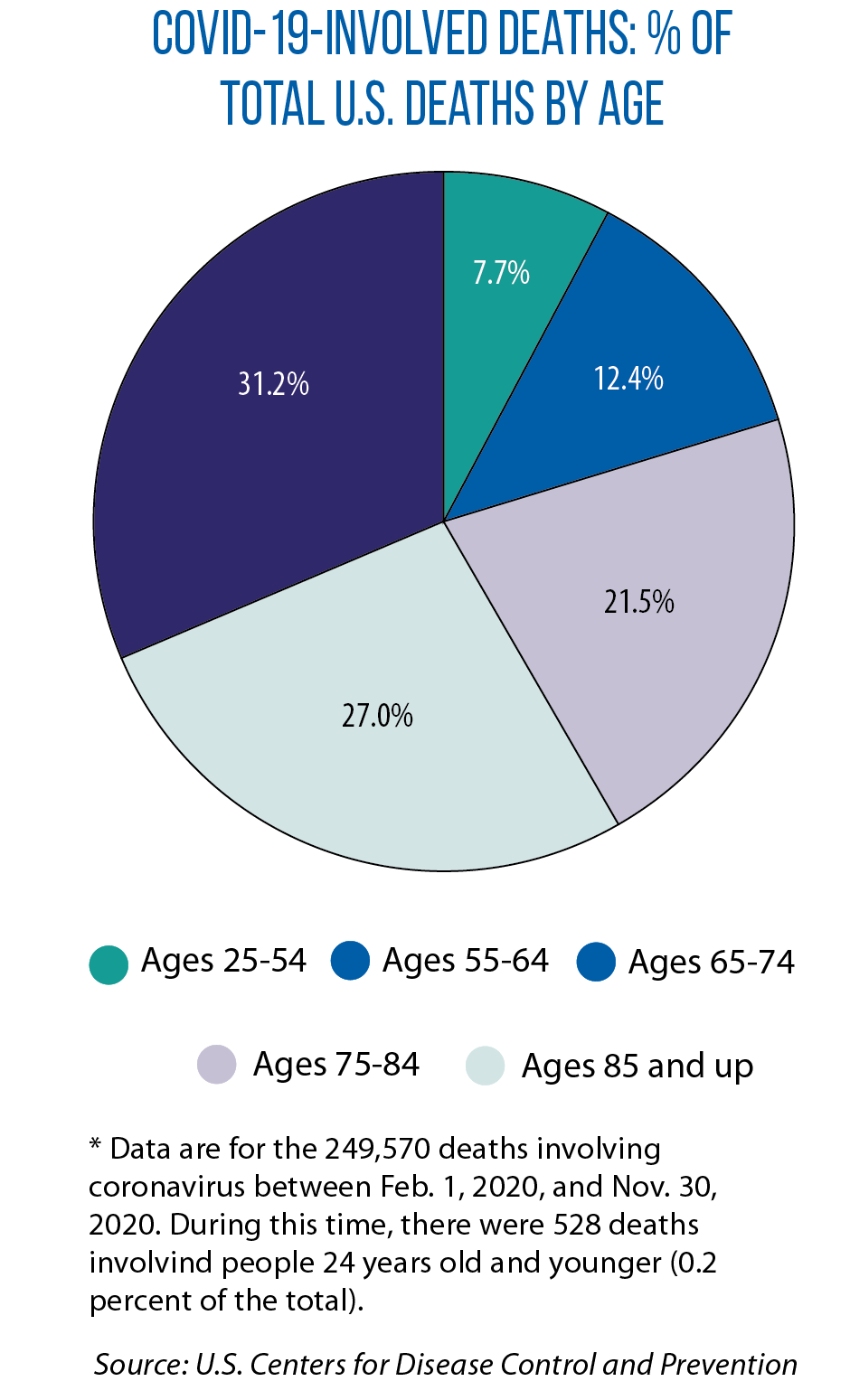

Late in 2020, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended a phased distribution of initial shipments of vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna, starting with frontline health care workers and the residents of long-term-care facilities.

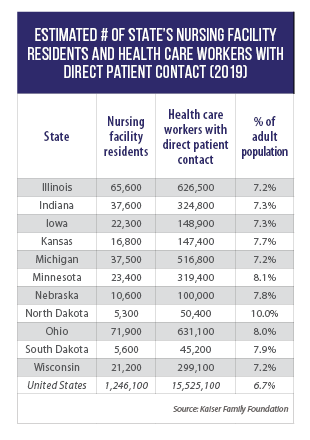

All Midwestern states’ vaccination plans assume that starting point, and these priority populations make up a significant percentage of the region’s total adult population — as high as 10 percent in North Dakota (see table).

States then generally lead from those groups to higher-risk populations (for example, seniors age 65 and older), and, as doses become more widely available, to the general populace.

The federal government paid for vaccines via “Operation Warp Speed,” and the CDC released $200 million to states for planning purposes, but hasn’t yet helped pay for storage, distribution, training and public education.

Iowa Rep. Shannon Lundgren, co-chair of The Council of State Governments’ Midwestern Legislative Conference Health & Human Services Committee, says legislators hold weekly calls with state health officials, but it’s not yet known if they’ll need to approve funding during the 2021 session for Iowa’s COVID-19 vaccination program.

“All of those things are just starting to come out now,” she said in December. “We have not yet talked about money. It may be something we have to do early on [in session].”

Another potential question for 2021: Should the vaccine be mandatory?

AB 11179, introduced in December in the New York State Assembly, calls for public health officials in that state to implement such a mandate if they “determine that residents of the state are not developing sufficient immunity from COVID-19.”

Targeted messaging can boost vaccination rates

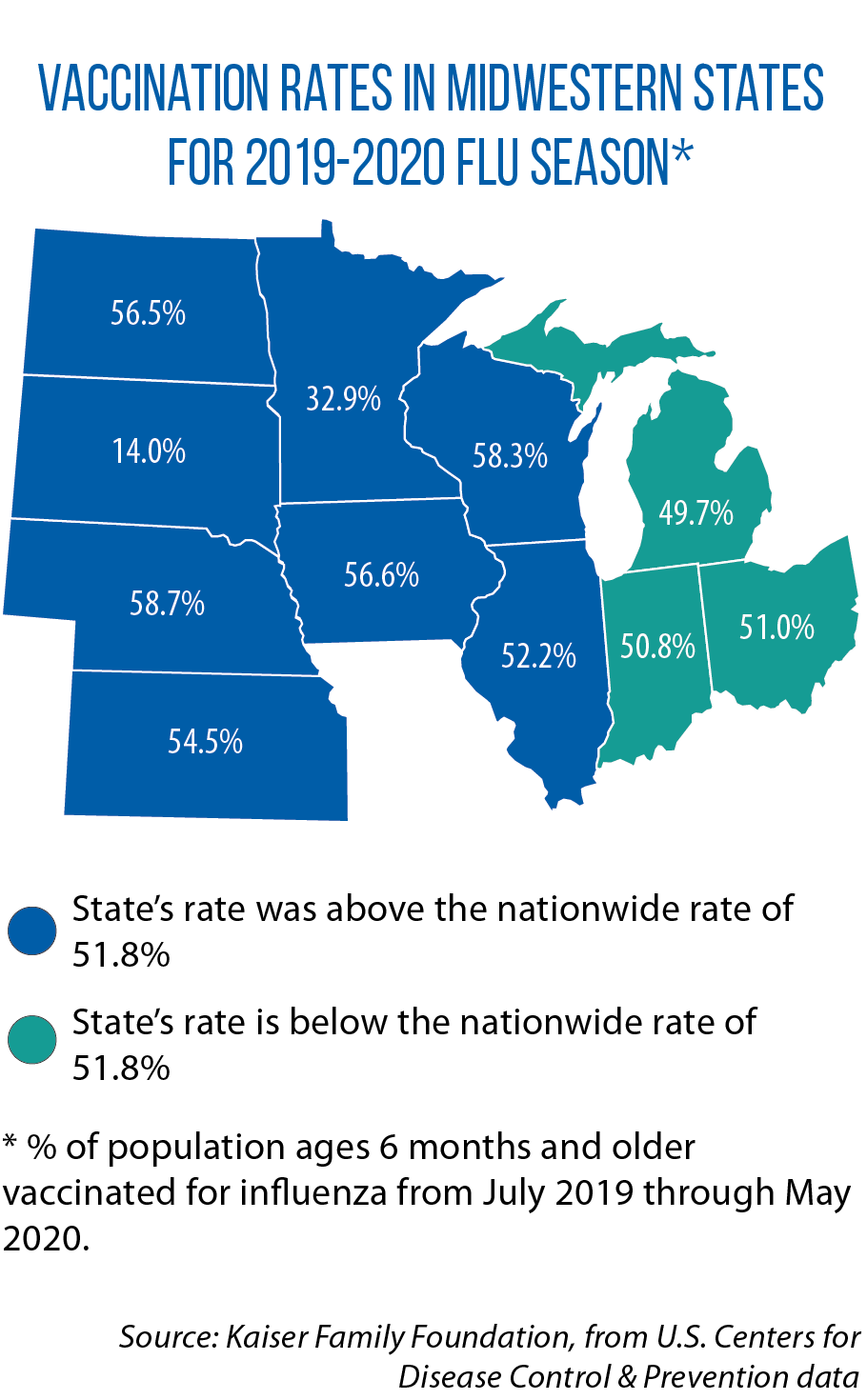

All Midwestern states’ vaccination plans include references to public communication, with many noting the need for messages targeting specific audiences and in multiple languages.

Minnesota’s plan, for example, says: “Existing relationships with partner and community organizations will be leveraged to help reach key audiences with information” about the new vaccines.

“To build trust and encourage cooperation with our recommendations, communications will be  respectful of people’s concerns and recognize that different communities will have different needs for information.”

respectful of people’s concerns and recognize that different communities will have different needs for information.”

Health officials in that state can draw on their experience containing a 2017 measles outbreak in the Somali-American community for guidance.

To bolster immunization rates, the state hired Somali speakers and crafted messages targeting schools, child care centers and the faith community. Somali imams helped by asking for information that they could pass on to their congregations. Rates increased after this targeted approach.

Michigan’s vaccination plan details how inter-agency and public communications plans will evolve with each phase of increased distribution, while North Dakota is planning to begin with a broad media campaign and adjust its approach as public response warrants.

Iowa’s plan does likewise (including weekly briefings for legislative caucus staff), while noting that a major component of the public awareness campaign is “ensuring all Iowans are able to receive and understand messages, regardless of an individual’s ability to read, speak or write English.” Nebraska’s plan states that “information shared must be evidence-based, truthful/credible, respectful and shared with a sense of urgency.”

Nationally, Osterholm says, it will be important to have scientists front and center “to discuss why it’s important to get the vaccination, and to show leadership by getting it ourselves.”

Meeting the challenge of storage, distribution

Not all potential COVID-19 vaccines will require ultra-cold storage, but Pfizer’s vaccine must be stored at or below minus-94 degrees Fahrenheit.

This could potentially create distribution bottlenecks: a state with few such storage sites would be limited in the number of doses it could handle at any one time.

But Osterholm says, “I’m confident that this is a very critical part of what [incoming Biden administration officials] are planning for.”

In a November press briefing, Julie Willems van Dijk, deputy secretary of the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, said ultra-cold storage, as well as a tracking of the different vaccines’ schedules, will be among the biggest challenges her department faces.

This fall, she said, the department was already locating and logging ultra-cold freezers for use in storage and distribution.

Dr. Stephanie Schauer, program director of the Wisconsin Immunization Program, said only a few ultra-cold freezers will be necessary because these vaccines can be safely kept in dry ice for up to 15 days.

“This is a pretty short time frame, but with some planning, it is possible for entities that don’t have that minus-80 degree storage to still be able to receive and administer the vaccine,” noted Schauer, adding Wisconsin’s manufacturers of dry ice offered assistance to ensure a steady supply.

COVID-19 vaccination planning and dissemination have been “even more complicated than we had ever imagined,” Willems van Dijk said. “It will be the most extraordinary public health intervention our state has ever seen.”

‘The vaccine isn’t vaccination’

States are coordinating with the CDC to track orders and shipments from the federal government, but in other policy areas, states must take the lead — for example, tracking distribution within their borders, monitoring who gets which vaccine, and reminding people who get a two-dose vaccine when it’s time for their second, follow-up shot.

States such as Illinois, Indiana, Kansas and Minnesota will make use of their existing vaccine registry systems to track COVID-19 vaccinations. Systems in Illinois and Minnesota can provide automated reminders for second-dose shots; the Minnesota Department of Health plans special training sessions on how to use this reminder feature.

Kansas and Michigan plan to give a card to vaccination recipients with instructions to save and have it available for the second dose. Michigan is also developing an optional second dose text reminder.

Osterholm warns against expecting miracles. Even after distribution of a vaccine, or multiple vaccines, begins, the pandemic won’t go away quickly; it will last through at least the second quarter of 2021, he says.

“The vaccine isn’t vaccination. Vaccinations are what will make the difference,” Osterholm adds.

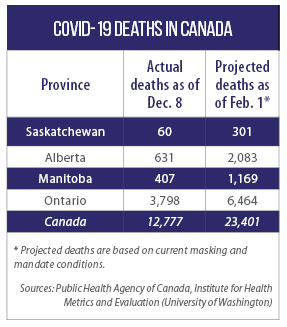

Former NATO Commander overseeing vaccination logistics in Canada; provinces have distribution plans in place

Saskatchewan’s health ministry announced in December that the province’s COVID-19 vaccination scheme would play out in three phases, starting with an “isolated pilot” of 1,950 doses for health care workers in the provincial capital, Regina, and then expanding as supplies of vaccine allow.

Like states vis-à-vis the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Saskatchewan’s plan is based on guidance from Canada’s National Advisory Committee on Immunization, which recommended that initial, limited doses of authorized COVID-19 vaccine(s) should be offered to:

based on guidance from Canada’s National Advisory Committee on Immunization, which recommended that initial, limited doses of authorized COVID-19 vaccine(s) should be offered to:

- residents and staff of congregate living settings that provide care for seniors;

- adults 70 years of age and older, beginning with adults 80 years of age and older;

- health care workers (including all those who work in health care settings, as well as personal support workers whose work involves direct contact with patients); and

- adults in indigenous communities where infection can have disproportionate consequences.

Saskatchewan’s pilot vaccination program was to be followed by “targeted” immunizations for health care workers in intensive care and COVID units and COVID testing/assessment staff, as well as residents in long-term care and “other vulnerable populations” — those 80 and older in all communities and those 50 and older in the province’s remote northern half.

Like the United States, Canada’s federal government signed deals with multiple vaccine manufacturers to deliver doses of any vaccine that clears clinical trials and wins approval from regulatory agencies.

In late November, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau named a former NATO commander, Major Gen. Dany Fortin, to oversee federal vaccine logistics and operations within a new branch of the Public Health Agency of Canada.

According to the Canadian Broadcasting Company, Trudeau said the country’s military “will assist in planning for and tackling pressing challenges, such as the cold-storage requirements for the promising Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. The military also will help Ottawa get shots to some indigenous and rural communities where health care services are limited at the best of times.”

Federal authorities allocated one ultra-cool freezer to Saskatchewan, and the province bought 25 such freezers to aid in distribution of Pfizer’s vaccine (it must be stored at extremely low temperatures). Manitoba Premier Brian Pallister said in early December that the province already had installed one specialized freezer to store the Pfizer vaccine and was awaiting four more, giving officials capacity to store one million doses.

In Ontario, Premier Doug Ford also has tapped a retired general to lead the province’s vaccine distribution program. Provincial health officials said a distribution plan was expected to be released by the end of the year. Alberta officials have said they expect to get 681,000 doses early in 2021.