Proposed Asian carp barrier gets federal backing; new rules on treatment of ballast water moving forward

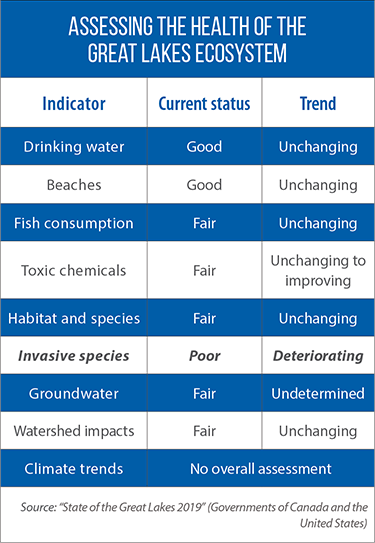

The year 2020 ended with two policy developments likely to shape future regional efforts to protect the Great Lakes from one of its greatest threats — the introduction and spread of aquatic invasive species.

As part of a spending bill approved in December, the U.S. Congress authorized an $858 million project to add a new electric barrier and other fish-control technologies at Brandon Road Lock and Dam near Joliet, Ill. The goal: keep Asian carp and other invasive species from reaching the Great Lakes via the Chicago Area Waterway System.

This fall, too, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency released draft standards for how the ballast water on oceangoing vessels must be treated.

Progress on Brandon Road

The new barrier and controls at Brandon Road are a project of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Such projects typically require a non-federal sponsor that pays for 35 percent of the costs, but Great Lakes advocates and congressional supporters were able to boost the federal share of Brandon Road’s costs to 80 percent. That still leaves a considerable amount of money needed for a project with a current price tag of close to $1 billion.

Illinois has signed an agreement with the Army Corps to be the project’s non-federal sponsor for the pre-construction engineering and design phase. And it will be receiving some financial assistance from a Great Lakes neighbor. Michigan has committed $8 million for this phase of the project. Illinois will contribute the remaining $2.5 million that is needed. The two states entered into an intergovernmental agreement in late December. More costs will come, and have to be covered, for the actual construction phase.

New rules, but not yet

Concerns about Asian carp are behind the push for the Brandon Road project. These species of fish were initially brought to the United States to control algae blooms and vegetation in aquaculture facilities in the South. They escaped and have spread throughout the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, which are connected to the Great Lakes via the Chicago Area Waterway System, where Brandon Road Lock and Dam is located.

But most invasive species, including sea lamprey and zebra mussels, came to the Great Lakes via the discharge of ballast water from oceangoing vessels.

“[It] accounts for anywhere from 55 to 70 percent of the reported introductions since 1959,” Sarah LeSage, aquatic invasive species program coordinator for the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy, said in December during a presentation to the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Legislative Caucus.

Preventing these introductions is the goal of the EPA’s proposed new rules, which include discharge-specific standards for 20 different types of vessel equipment and treatment systems. They are the result of the Vessel Incidental Discharge Act of 2018.

Great Lakes advocates largely supported this law because it ensures that the EPA can regulate ballast water discharges as a pollutant under the Clean Water Act, and thus establish science-based treatment standards. But these gains in federal protection will come with a loss of policy authority for states, which will be largely barred from setting more-stringent standards of their own. Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin currently have state-level permitting programs and/or requirements for ballast water management.

“That [pre-emption] happens when the standards are final, effective and enforceable,” LeSage said. These new federal rules, which will be enforced by the U.S. Coast Guard, could take effect as early as 2023, she said. At that point, the only policy pathway for Great Lakes states will be for their governors to petition the EPA and ask for more-stringent standards.