Decision 2021: Future of voting laws has become one of this year’s most-watched policy debates in state capitols

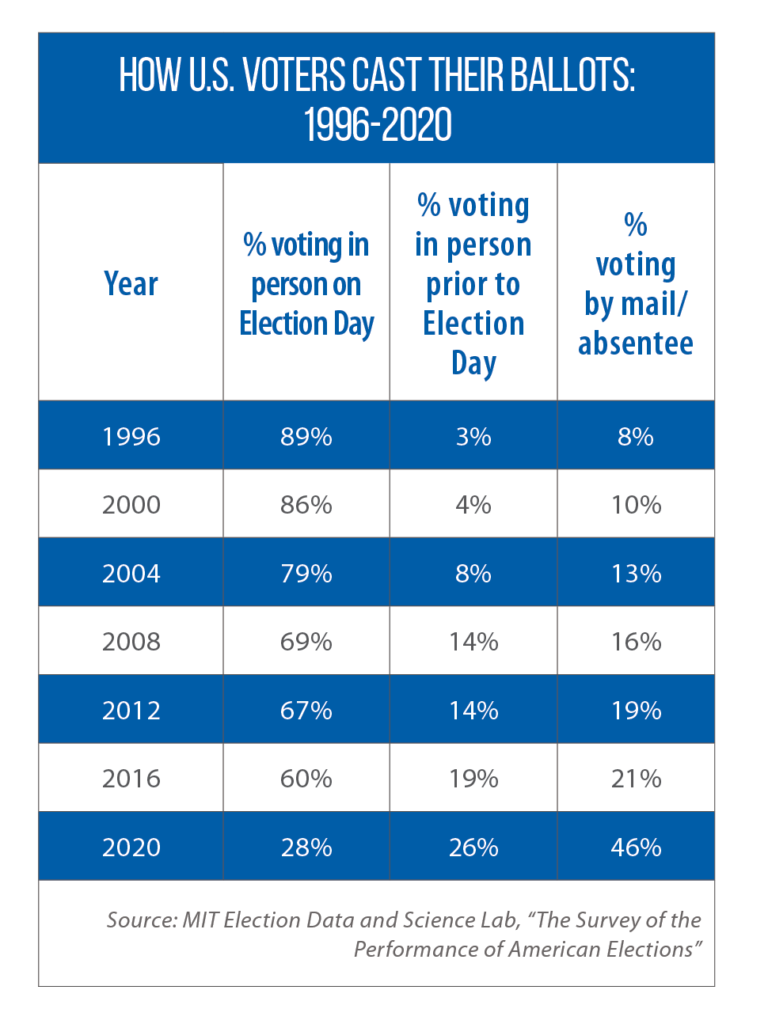

After a year in which a pandemic forced states to find new ways of administering and holding elections, competing policy proposals during the 2021 legislative sessions would take states in much different directions.

Some look to build on 2020.

In Illinois, for instance, the recently signed HB 1871 codifies curbside voting and local election officials’ use of drop boxes, an option for voters (along with the mail) to return completed absentee ballots. Lawmakers also authorized the allocation of federal Help America Vote Act dollars to pay for ballot drop boxes.

As part of its tracking this year of election-related bills, the Brennan Center for Justice listed Illinois HB 1871 as one of more than 800 proposed measures in U.S. states designed to increase voter access.

The center also has categorized more than 350 pieces of state legislation that it said would have the effect of restricting access. One of those measures is Iowa’s SF 413, which was signed into law in March. Among its many provisions: reducing the time period to apply for and return absentee ballots, shortening the state’s early-voting period (from 29 days to 20), and limiting the number of drop boxes per county.

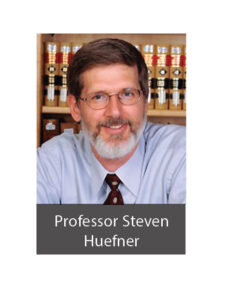

“We have always seen state legislatures, somewhere in the country, thinking about how they might reform or update their election mechanisms,” says Steven F. Huefner, a professor at The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law. “But this year is completely different. We’ve never seen anything like the volume or the aggressiveness with which states are moving.”

Huefner is a leading regional expert on state laws and voting, and the co-author of “From Registration to Recounts: The Election Ecosystems of Five Midwestern States.” CSG Midwest interviewed Professor Huefner to get his perspective on this year’s surge of legislative activity.

Q: A lot has been made about how highly partisan the debate in state capitols has been this year. Is that something new or different this year, or has it always been part of U.S. election law and policy?

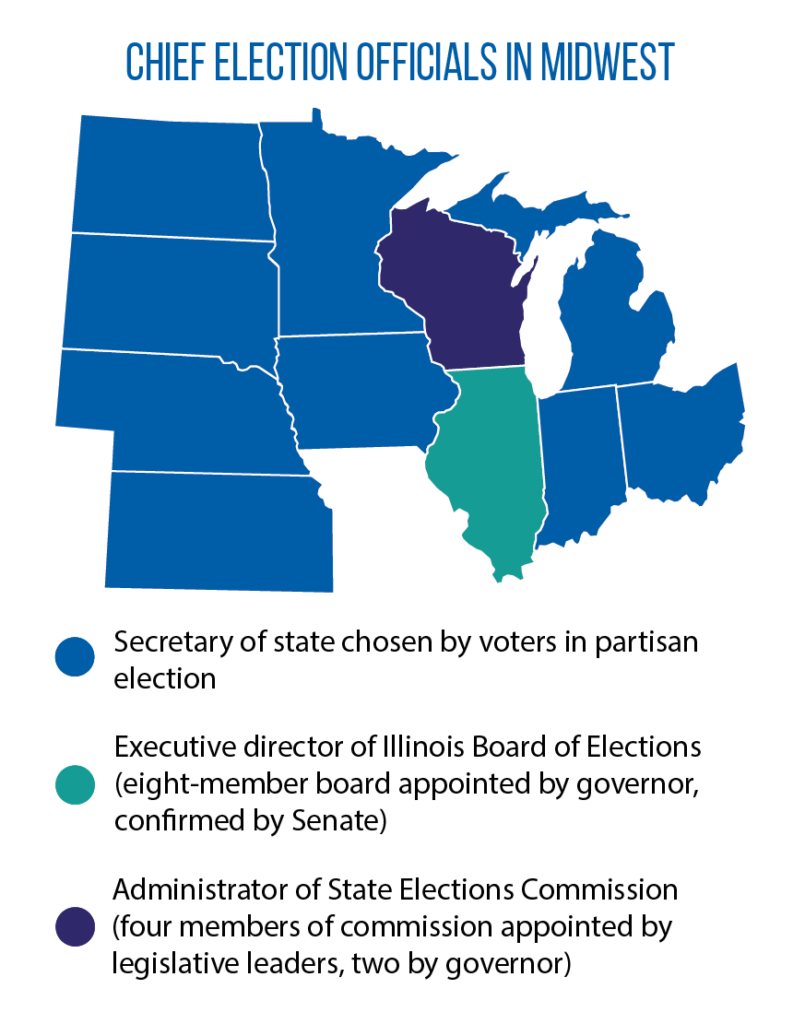

A: There’s always been some degree of partisanship. The United States, in fact, is among a very small number of democracies that allows partisans to be in charge. American elections are primarily run by the states, and in most instances, that is the secretaries of state. They try to do their jobs fairly and neutrally, but you can see the partisan pressures. Whereas in other countries, you have independent electoral commissions that run the whole thing. There are some U.S. states that try to do this, and Wisconsin is probably the best example.

But it does feel like we’re at a point in time right now when partisans on both sides keep ratcheting things up, and the battles are becoming more and more pitched. It’s disappointing. Because when it comes to the fundamentals of democracy, everybody ought to have a commitment that all eligible voters should be able to participate with minimum burden or difficulty.

Q: What have you learned about what works best in terms of election administration and laws?

A: I’d start by saying it really should be structured so that the officials primarily running it are nonpartisan. We should have nonpartisan election administration. I’d also say the voter registration system should be automatic or allow for same-day registration. And we should have a system where anyone who wants to be able to cast a ballot by mail, or an early vote in person, should be able to do it. That said, it’s reasonable to limit early voting to just a couple of weeks, making sure some weekends are available. You don’t need a month of it. In some ways, the more it’s limited, the more it means voters are making decisions based on the same information.

primarily running it are nonpartisan. We should have nonpartisan election administration. I’d also say the voter registration system should be automatic or allow for same-day registration. And we should have a system where anyone who wants to be able to cast a ballot by mail, or an early vote in person, should be able to do it. That said, it’s reasonable to limit early voting to just a couple of weeks, making sure some weekends are available. You don’t need a month of it. In some ways, the more it’s limited, the more it means voters are making decisions based on the same information.

Q: What about requirements for voter identification?

A: It’s certainly fair to say that everybody who votes needs to authenticate that they’re an eligible voter. And there are ways to do that. I don’t think it’s wrong to require an identifying number or some other method. Historically what we’ve done is just make voters sign their name and use signature matching. It turns out that signature matching is pretty imprecise. But this is the 21st century, and we have other ways to protect against impersonation. States can experiment with that. It should be done in a way that does not end up creating a real burden to some voters, especially if the burden is disproportionately affecting categories of voters — for example, lower-income voters.

Q: Are they any particular approaches you would like to see states try?

A: I’d be interested in having people think about whether state IDs should themselves be automatically issued. I know that idea gets resistance from across the political spectrum. But gosh, it would sure help voter administration and help build confidence if everybody got a voter-ID card.

Q: The U.S. House has passed HR 1, which would require states to have automatic voter registration, allow same-day registration, offer 15 days of early voting and permit any eligible voter to cast a vote by mail. Does this level of detail surprise you?

A: It would certainly represent a dramatic increase in the amount of federal regulation on state elections. It’s a reaction to what has been happening in the states and the U.S. Supreme Court. The Constitution gives Congress the power to set the terms of the elections of federal officeholders. It’s always seemed uninterested in using that power, until now.

Q: Looking back to 2020, what are your views on how elections were administered by states?

A: A foundational principle of voting processes is that they should be designed in careful ways that give us confidence that only eligible voters are voting. Because people agree with that, the mechanisms we had before [2020], including for absentee and early voting in person, were quite well-designed and resistant to manipulation.

And then we had the pandemic. Many states then made adjustments to accommodate voters. I think it’s fair to say those accommodations, even though they were adopted almost on the fly, were still quite safe. Therefore, even though there was this dramatic increase in the volume of votes cast by mail, it was still done in a way that was reliable and that we could be confident that the votes were being cast by eligible voters.