Demographic truths and consequences for the Midwest

In many parts of the Midwest, birth rates are falling, people are leaving for other states and the population is aging; the result could be a difficult policy landscape for leaders

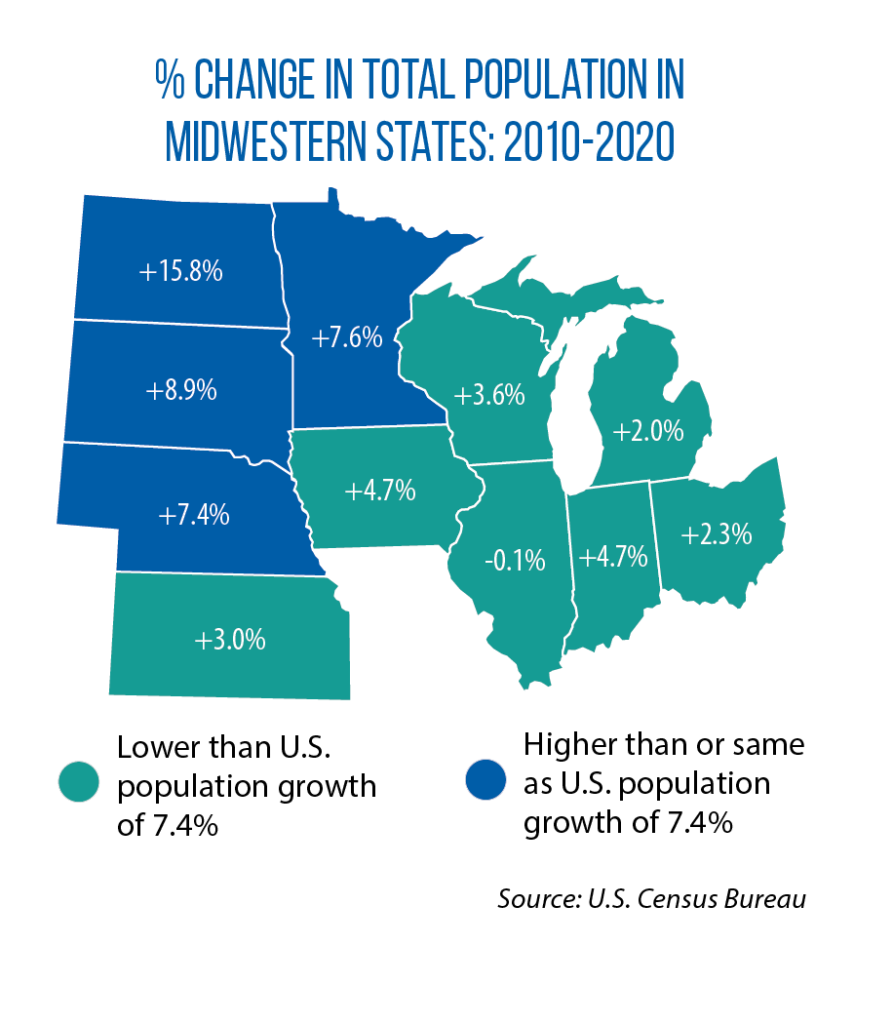

The big national headline from recently released U.S. Census results was this: Over the past decade, the nation’s population grew at its slowest rate since the Great Depression.

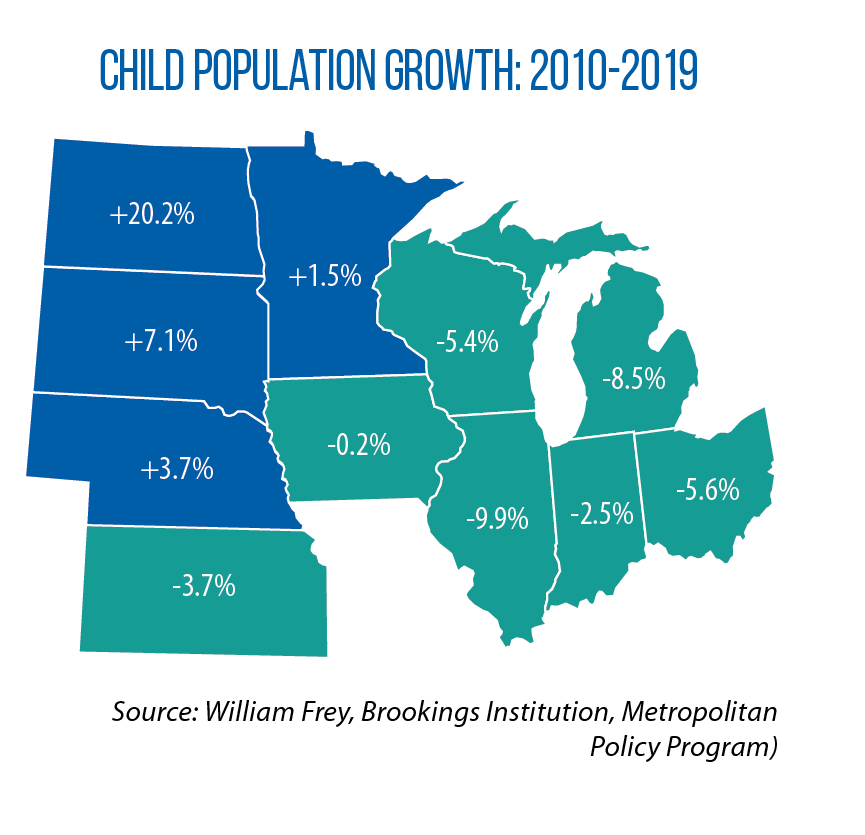

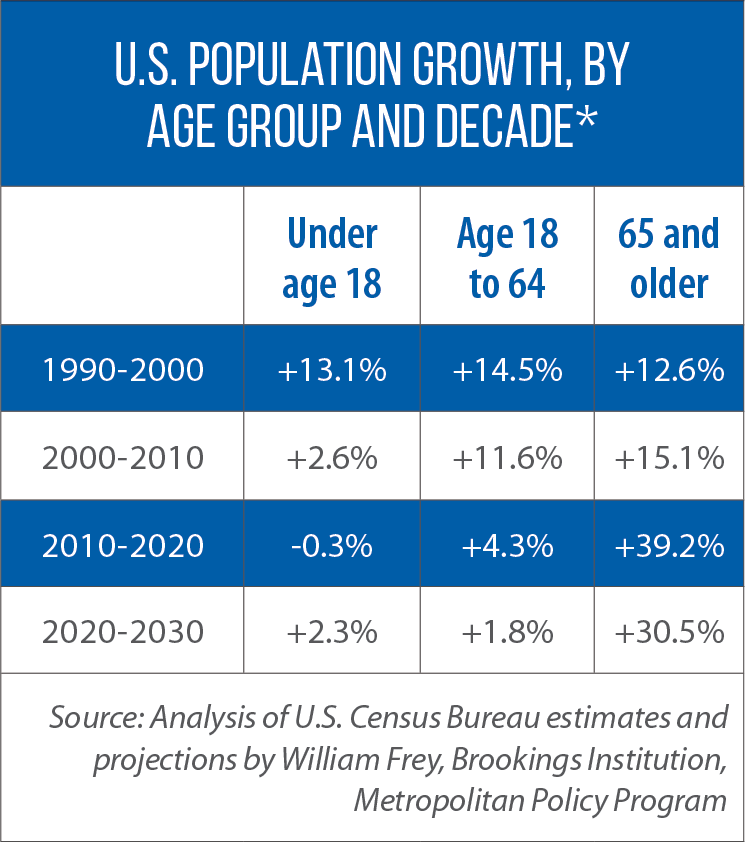

Dig deeper, and the numbers become of even greater interest, and potential alarm, to the Midwest’s legislators and other leaders. “Everywhere, the aging population is growing,” says William Frey, a demographer and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program. “The difference between winners and losers, demographically, will be what we see in those younger years — whether there is growth or decline in the under-18 population, which then leads into labor-force participation.”

the Midwest’s legislators and other leaders. “Everywhere, the aging population is growing,” says William Frey, a demographer and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program. “The difference between winners and losers, demographically, will be what we see in those younger years — whether there is growth or decline in the under-18 population, which then leads into labor-force participation.”

For much of the Midwest, the trends point to many communities being on the losing end. With some exceptions, the region traditionally has not been a magnet for migrants, domestic or international, so its growth has depended on “natural” increases — more births than deaths. But one of the more striking demographic shifts in recent years has been a nationwide narrowing of that birth-to-death ratio; in fact, Professor Kenneth Johnson says, nearly half of the nation’s counties experienced natural decreases in the population in 2019 — even before the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Not only do you not have fewer young people having babies, but the people left behind have all aged in place,” says Johnson, a senior demographer at the University of New Hampshire’s Carsey School of Public Policy. “You get out 20 or 30 years, and you start seeing mortality rise. It becomes sort of a vicious cycle.”

More seniors, fewer workers

One measure often used by demographers is what’s known as the “old age dependency rate” — a calculation of the number of seniors compared to the number of working-age adults.

“It’s moving upward all the time,” Frey says of national trends. “And we’ve seen projections that it could go from 28 percent [today] to as high as 45 percent, depending on immigration numbers.” (Higher immigration numbers lower the rate because immigrants tend to be of working age.)

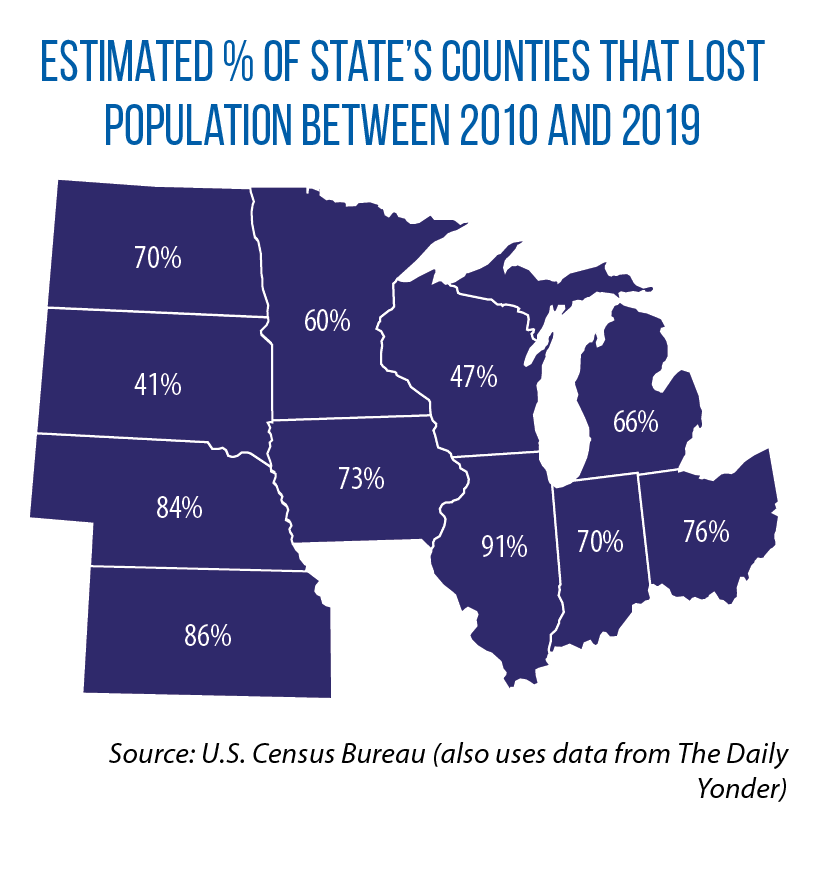

In the 11-state Midwest, between 2010 and 2019, most counties lost population. In Illinois and Kansas, for instance, 91 percent and 86 percent of the counties, respectively, had declines in their number of residents (see map).

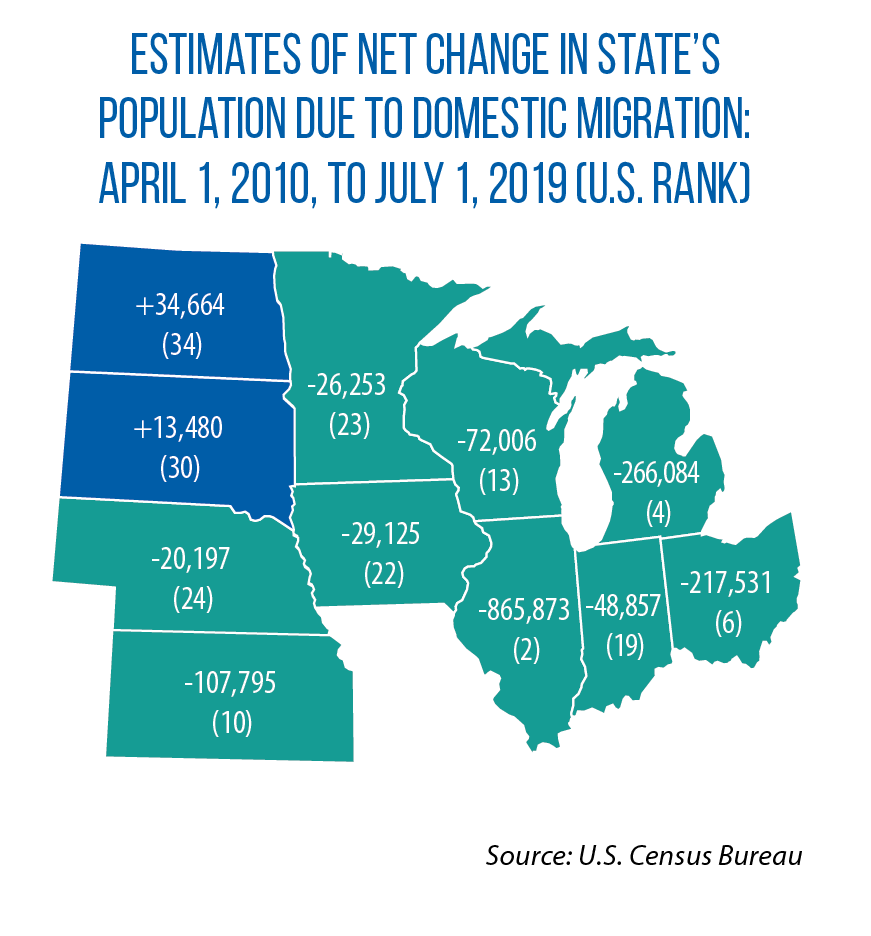

This has been most likely to occur in rural areas not adjacent to a metropolitan region. Along with fewer births and more deaths, another cause of these declines has been the loss of young people to domestic migration. Most states in the Midwest have lost residents, sometimes hundreds of thousands of them, to other states over the past decade (see map).

And there are the likely short- and long-term effects of the COVID pandemic — fewer births and, ultimately, declines in the working-age population.

“It pushes us in a direction that we were hoping to move away from,” Minnesota state demographer Susan Brower says. “It’s going to take 16, 18 years to reach us, but it will be felt, and Minnesota already has had a hard time with labor-force growth.”

She adds that these population trends, namely what’s happening in younger cohorts, is a particular challenge for Midwest and Northeastern states.

“In and of itself, I don’t think having slow growth is a problem,” she says. “But the way that our economies are set up, and even our public budgets, we assume there is growth in the future — ever-expanding markets, ever-expanding numbers of producers. We fund our government through consumption and production. That’s a foundation we don’t think of very often, but it’s a reality.

“So when we know there are demographic factors coming that make it hard or impossible to grow your way out of [economic or budgeting issues], that becomes a challenge.”

Policy options for states

Can this loss of population, either in the nation, an entire state or parts of a state, be stemmed? Frey believes that will be difficult to achieve without a rise in immigration from other countries.

“It’s going to be the lifeblood of our growth, and really the only way to keep the growth rate going more on that downward track,” he says.

Frey also has written about the policy implications of the “child deficit.” Between 2010 and 2019, the number of children living in most Midwestern states declined (see map).

“In the 1960s, kids were all over the place; they were a huge part of the population,” Frey says. “That’s not going to be the case anymore.”

For states, that means making the most of every child you have — closing achievement gaps and ensuring all young people are prepared to be part of the labor force and to contribute to local economies. There also will be an even greater premium on retaining and drawing in individuals in their 20s and early 30s.

“Those are the ages you want to attract people, because that’s when a permanent decision on where to live, where to raise a family, is going to be made,” Frey says.

Above all else, he adds, these individuals must see a chance for economic opportunity and jobs. According to Brower, population declines have been most severe in Minnesota counties that lack a diverse mix of employment options.

“They don’t have a metropolitan area or some kind of economic engine, other than agriculture, or farming really,” she says.

In the past, Johnson says, the first decision businesses would ask when considering where to locate was, “How are the weight limits on the bridges?” “Now the first question is about internet service,” he adds. “Companies don’t even want to think about places that don’t have high-quality services.”

State investments in infrastructure — broadband, transportation, and water — are one critical way to position local communities to attract businesses and people alike, Johnson says. Likewise, factors such as increased internet connectivity, the rise of stay-at-home work and new remote learning opportunities in K-12 education could help.

“For states that have had problems finding workers, and for rural areas that have had a hard time holding on to residents, this potentially could be a game changer — if you can get the broadband in place,” Brower says. “It sets up a dynamic where workers don’t have to be as tied to the geography of their workplace.”