The Midwest is again losing U.S. House seats and Electoral College votes, but Minnesota held its share — barely

In the years leading up to the 2020 census, Minnesota’s political and community leaders knew it would be close: Could the state hang on to all of eight of its existing U.S. House seats and all 10 of its Electoral College votes? Some population estimates and trends showed the state losing in reapportionment, others showed the state could hold on to what it had.

The final results turned out to be incredibly close, with Minnesota barely hanging on, and the state of New York losing a seat as result. According to Minnesota Public Radio: “If Minnesota had counted 26 fewer people — or New York just 89 more — the seat would have switched states.”

As Minnesota state demographer Susan Brower notes, had her state lost that seat, each of the remaining seven districts would have had to grow by 102,000 people, ”setting off a complex realignment or redistricting of the state’s political map.” “The impact in Greater Minnesota [the state’s areas outside the Twin Cities metropolitan area] where the districts are already very large would have been especially difficult.”

Minnesota’s state and local governments and its various community groups weren’t simply observers, watching to see what would happen with the 2020 census count. They planned for and executed an aggressive outreach campaign to ensure that high rates of Minnesotans would return their census forms. Brower and others at the State Demographic Center helped lead the way, thanks to a budget appropriation of $1.6 million to promote the census. (That figure is much higher than what the center has received in past decades for promotion and awareness.)

“Our office almost 100 percent shifted over the last couple of years to census engagement,” Brower says. “It was brand-new to me. It’s not something they do or you learn in a demography school. But it was fun. We had people inside and outside of government who worked really hard on it.

“It was two years of promotion all the time.”

People with experience in political campaigns were hired to help with promotion efforts, and new grants went to community groups. A texting campaign, with links to fill out the census form, reached more than one million Minnesotans. And after the pandemic hit, the center set up a phone bank for volunteers to call people from certain ZIP codes that have traditionally been slower to respond to the census. All of these efforts paid off: The state reported a nation-leading self-response rate of 75.1 percent of households and was able to secure the 435th seat in the U.S. House by the slimmest of margins.

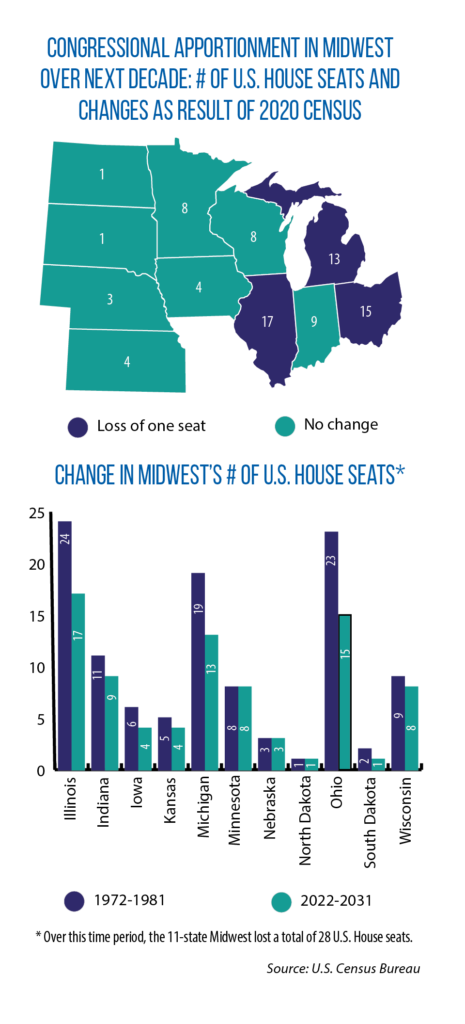

Still, the Midwest as a whole was once again a net loser on reapportionment. The region is losing three congressional seats, one each in Illinois, Michigan and Ohio. This also means three fewer votes for the region in the vote for president. In 1972, the 11-state Midwest held 133 Electoral College votes; that was 49.2 percent of the 270 needed to win the presidency. In contrast, in 2024, 105 of the Electoral College votes will come from this region, 38.9 percent of the total needed to win.

According to Bill Frey, demographer at the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program, the Midwest’s share of the U.S. population (Missouri included) has been falling since at least 1920 — from 32 percent that year to 21 percent in 2020.