Pains of rising drug costs

Recent legislative actions have focused on capping insulin co-pays, regulating pharmacy benefit managers — but other policy ideas are under consideration

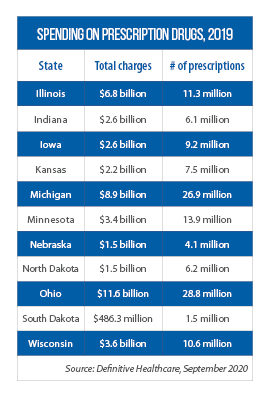

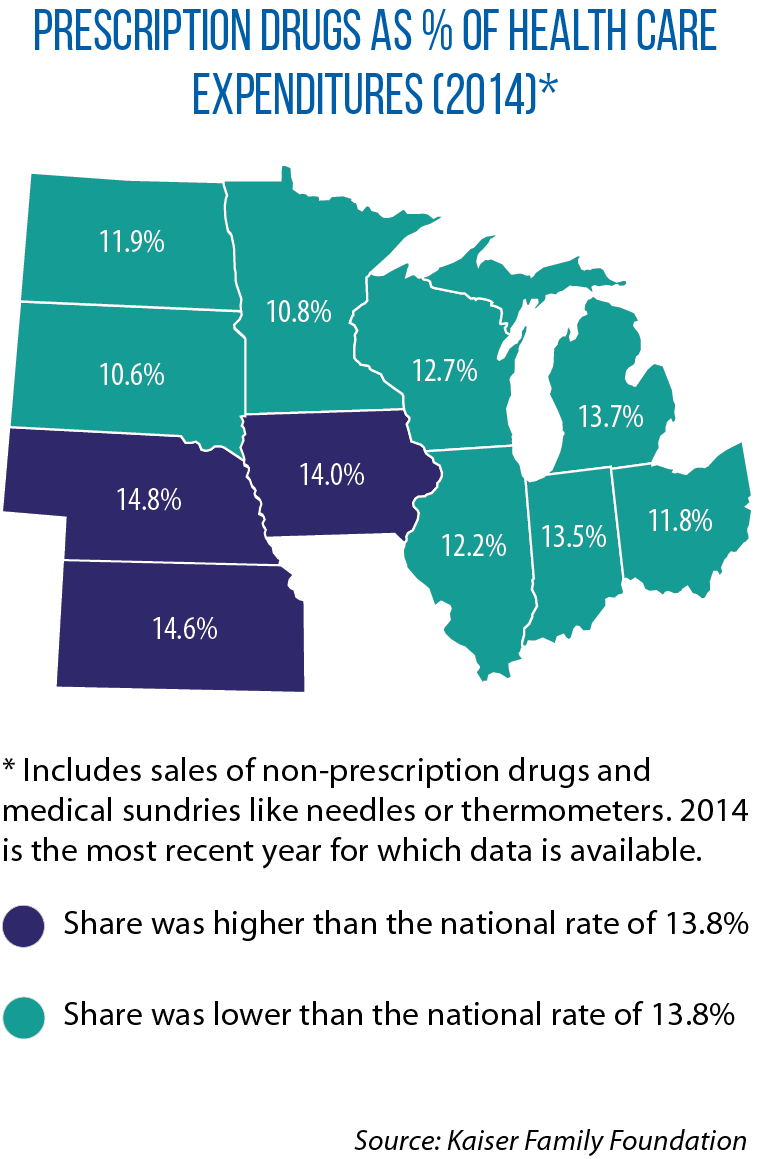

Of all pre-pandemic problems vexing state health policymakers, prescription drug pricing continues to draw legislative attention and action as rising costs create budgetary headaches for constituents and state programs alike.

States have responded in recent years with measures to regulate pharmacy benefit managers (the “middlemen” between health insurance plans and pharmacies), cap co-payments for some drugs such as insulin, and create task forces to explore the opaque world of prescription drug pricing.

Others have adopted or are considering the wholesale importation of drugs from Canada, as well as newer ideas such as the creation of prescription drug affordability boards, the use of international price referencing and other models to bend the price curve downward.

New insulin cost caps

With last year’s passage of SB 677, Illinois became the first Midwestern state (and the second nationwide, behind Colorado) to limit insulin co-pays for health consumers. The Illinois cap is $100 for a 30-day supply.

Minnesota followed in April 2020 with the Alec Smith Insulin Affordability Act (HF 3100), named for a 26-year-old who was unable to afford the $1,300 monthly cost of insulin and diabetes supplies and died rationing insulin after aging out of his parents’ insurance plan.

Under this law, eligible individuals in urgent need of insulin can go to their pharmacy once in a 12-month period and receive a one-time, 30-day supply of insulin for a $35 co-pay (applicants can receive a second 30-day supply in certain cases). Manufacturers must reimburse pharmacies for the insulin they dispense or send replacement insulin at no cost.

Minnesota also requires manufacturers to provide insulin to eligible individuals for up to one year, with the option to renew annually, in 90-day increments for a co-pay of no more than $50.

In March 2021, a U.S. District Court rejected a lawsuit challenging Minnesota’s law as unconstitutional.

Rising prices have spurred these actions in Illinois and Minnesota, as well as in other Midwestern states.

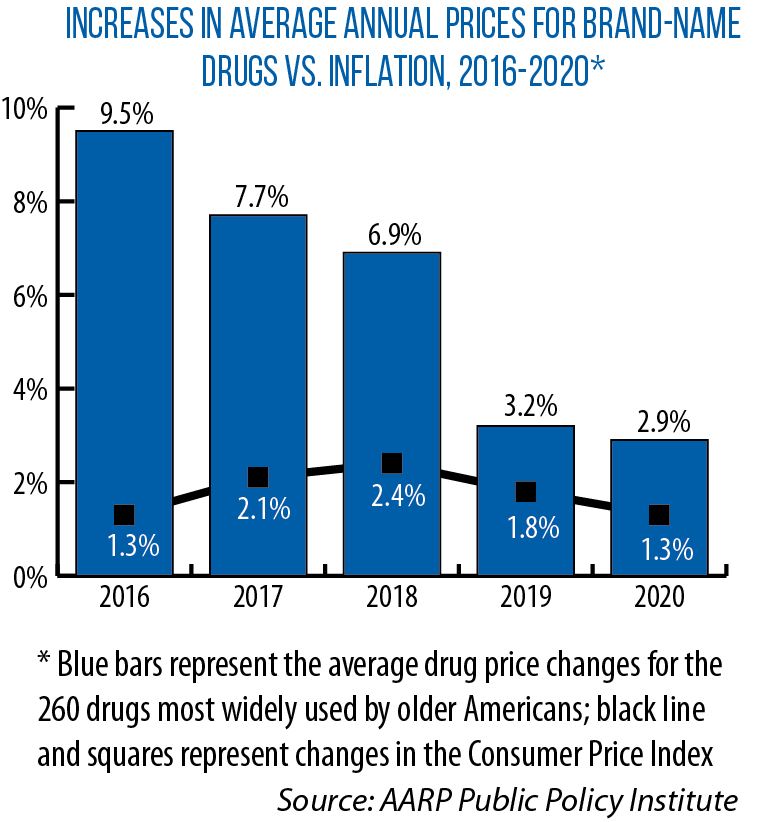

“The average price of drugs prescribed to treat diabetes, heart disease, depression and other common conditions has more than doubled,” Michigan’s Prescription Drug Task Force noted in its December 2020 report, while prices of the most commonly prescribed drugs for older patients rose “more than 10 times the rate of inflation within five years.”

In January, a Rand Corporation study found that average list prices in the United States for prescription drugs in 2018 were “significantly higher” than in other countries — 2.56 times higher than those seen in 32 other developed countries, while brand-name drug prices averaged 3.44 times higher.

In a July 2020 presentation to the Ohio Prescription Drug Transparency and Affordability Council, the drug manufacturers’ industry group PhRMA noted that prescription drug prices have actually been stable since 2010, and that 46 percent of spending on brand-name drugs goes to entities other than the manufacturer.

In that presentation, Kipp Snider, PhRMA’s national vice president for state policy, said most insured patients’ out-of-pocket spending is based on a drug’s full list price (the price set by a manufacturer) and that negotiated savings should be shared with patients.

PhRMA supports state policies to pass these rebates directly on to patients at pharmacy counters, allowing patients

to apply manufacturer coupons toward their deductibles, and having medications covered from the first day of insurance coverage, Snider said.

‘Unsustainable track’

So, what can states do to address concerns about rising prices?

This question was central to the work of task forces in at least three Midwestern states: Michigan’s and Wisconsin’s panels were created by pre-pandemic executive orders, Ohio’s was legislated as part of the state’s FY 2021 operating budget (HB 166).

“To solve the problem, you have to see the problem. Transparency is the biggest issue facing our health care system,” says Ohio Rep. Thomas West, co-sponsor with Rep. P. Scott Lipps of HB 336.

That bill would further regulate PBMs and require that cancer patients be given prescriptions for oncological drugs within 72 hours.

Transparency throughout the prescription drug supply chain is also important to find savings after manufacturers set their list prices, says the October 2020 final report from the Wisconsin Governor’s Task Force on Reducing Prescription Drug Prices.

“Detailed and often opaque agreements between entities throughout the supply chain” make finding savings difficult, a situation unlikely to change “until greater transparency is infused throughout [the chain],” the report says.

While these state task forces drew similar conclusions on the need for more supply-chain transparency, as well as varying degrees of new PBM regulation, each panel’s recommendations have — so far — met different fates.

Michigan’s Prescription Drug Task Force also suggested co-pay caps on insulin and other drugs, the use of international reference rate pricing, and setting price controls and rebates for consumer cost-sharing.

As part of its work, the group reviewed relevant bills proposed during the Michigan Legislature’s 2020 session, none of which advanced. Some were revived this year as part of a 15-bill package (HBs 4345-4359) approved in March by the House.

Among those bills are co-pay caps of no more than $50 for a 30-day supply of insulin (HB 4346) and pricing transparency requirements for manufacturers (HB 4347), hospitals (HB 4349) and pharmacies (HB 4352).

The idea of focusing on transparency, or “enlightening the murky middle” of the pharmaceutical distribution chain, is to understand how prices change on the path from manufacturer to end user, says Michigan Rep. Bronna Kahle, vice chair of the CSG Midwestern Legislative Conference’s Health & Human Services Committee.

That benefits patients and others at different points of the chain, she says.

HB 4353, which Kahle sponsored, would allow patients to apply the value of manufacturer’s coupons toward their deductible and out-of-pocket maximum.

“We have to do something,” Kahle says. “Something has to happen here because [prescription drug pricing is] arguably on an unsustainable track.”

In his proposed 2021-23 budget, Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers incorporated 20 of 27 suggestions made by his Task Force on Reducing Prescription Drug Prices, including an insulin co-pay cap, required reporting of drug price increases by different actors in the supply chain to identify where savings can be found, and drug importation from Canada.

All 20 proposals were struck from the budget by the Legislature’s Joint Committee on Finance. But Task Force Chair Nathan Houdek, Wisconsin’s deputy commissioner of insurance, says some of them may return as stand-alone legislation.

In its 2020 report, Ohio’s Prescription Drug Transparency and Affordability Council suggested legislators consider:

• establishing a single drug purchasing plan for all public (not just state) employees and a single, statewide formulary (list of covered drugs) for all state entities;

• requiring more clarity and accountability in PBM contracts;

• ensuring health equity is a consideration when developing prescription drug policies; and

• seeking “additional ways to benefit consumers,” such as applying manufacturer coupons to deductibles, covering drugs without deductibles in high-deductible health plans, and applying rebates to patients at the point of sale.

Another recommendation: consider whether a New Jersey-style “reverse auction” for PBM services could work in Ohio.

A 2016 New Jersey law (S 2749) authorized reverse auctions for PBM services in which bidders must agree to offer the same contract terms and compete only on price, with the least expensive offer winning.

New Jersey officials estimate the process will save $2.5 billion from 2017 through 2022.

Regulating ‘middlemen’

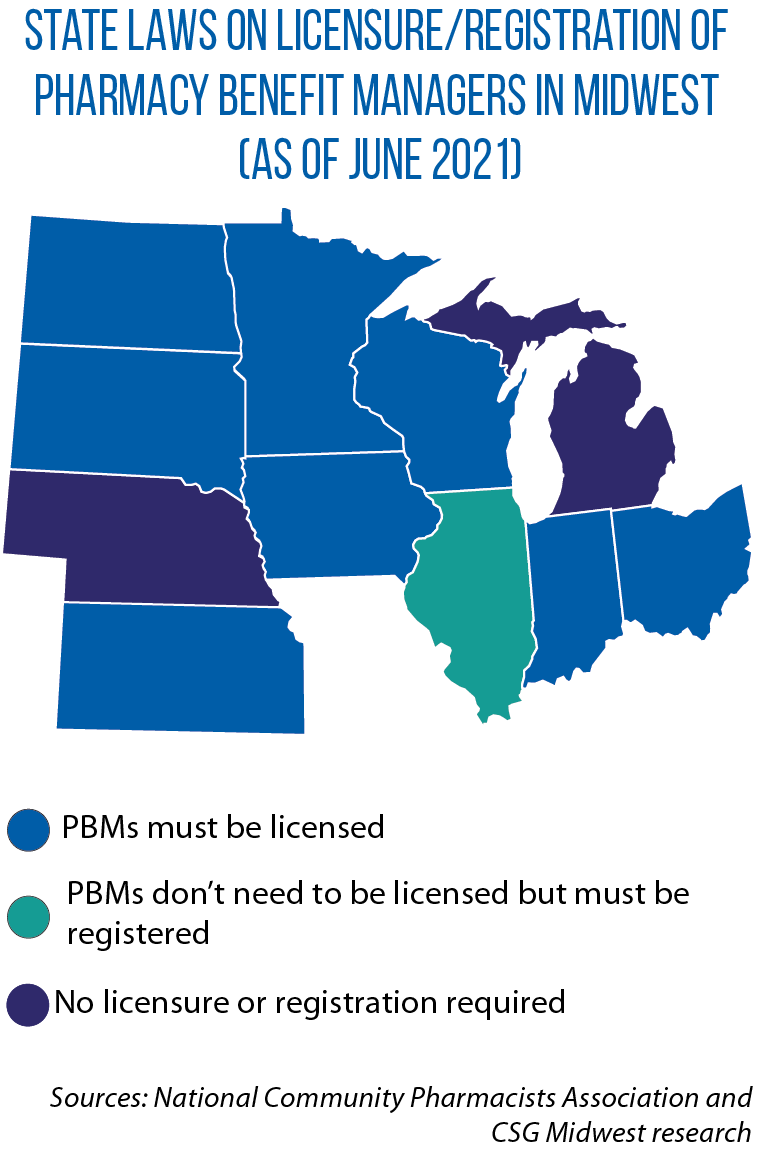

In Wisconsin, one measure that did advance to become law was SB 3, which requires pharmacy benefit managers to be licensed by the Office of the Commissioner of Insurance and to provide annual reports on rebates received from manufacturers but not passed on to health plan sponsors.

With the signing of this law, Wisconsin became the latest Midwestern state to license and regulate PBMs (Indiana and Minnesota also require them to be licensed).

Ideally, a pharmacy benefit manager leverages the aggregate purchasing power of health insurance policyholders by negotiating price discounts with pharmacies or prescription home-delivery services, as well as securing rebates from pharmaceutical manufacturers.

To many, however, PBMs have become pricey middlemen cutting secret deals and prohibiting insurance companies and pharmacies from discussing costs and/or reimbursements with patients.

In recent years, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa and Minnesota have passed laws requiring PBMs to share information transparency on pricing and rebates with pharmacies and/or administrative organizations.

Iowa in 2018 also restricted PBMs from prohibiting pharmacies or pharmacists from discussing cost information with covered individuals, or from selling more affordable drug alternatives.

South Dakota in 2019 enacted HB 1137, which limits what PBMs can charge and bars them from discriminating against pharmacies participating in certain health plans. It also prohibits PBMs from setting patient co-pays/coinsurance higher than the cost of a prescribed drug.

Houdek says PBM regulation is a piece of a holistic approach to prescription drug prices, “but, in and of itself, isn’t enough to solve the drug price issue.”

He also cautions that time will tell whether PBM regulation will help bend the price curve downward.

“An argument could be made that we haven’t had enough time yet to see if it’s having an impact,” he says.

New ideas, new solutions?

A newer policy idea from the National Academy for State Health Policy is international price referencing — looking to cap drug prices at no more than what’s paid in Canada’s four most populous provinces (Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario and Québec).

North Dakota lawmakers considered but didn’t pass SB 2170, which was based on the academy’s model bill for such a program.

It would have annually determined maximum retail prices for the 250 most expensive prescription drugs identified by the state’s public employees’ retirement system by comparing the wholesale acquisition cost to price data from those provinces. Cost savings would have been passed on to consumers.

While unsuccessful, the North Dakota measure shows that interest in international price referencing is “building,” says Maureen Hensley-Quinn, the academy’s senior program director.

“I won’t be surprised to see a bill pass in two to three years,” she says.

Another academy policy idea is establishing “prescription drug affordability boards,” similar in intent to existing state public utility commissions.

According to the organization’s website, the boards “investigate high-priced drugs and, when necessary, set more-affordable rates for certain drugs for purchasers within a state” and could establish health care provider and hospital payment rates.

In 2019, Maryland became the first state to enact legislation creating such a board. In 2021, nine states — including Minnesota (HF 801/SF 1121) and Wisconsin in the Midwest — are considering doing so. In Wisconsin, however, it was one of the ideas stripped from Gov. Evers’ proposed budget.

“[This was] kind of an odd year because pandemic response dominated a lot of states’ legislative sessions,” Hensley-Quinn says, adding she expects to see more action on prescription drug prices in 2022.