Support for expanding expungement eligibility builds in Wisconsin as result of legislative changes

Today, most Wisconsin residents convicted of a crime, even a nonviolent felony or a misdemeanor, have little chance of expunging the offense from their records.

One of these many Wisconsinites (an estimated 1.4 million have a criminal record) told his story to Rep. David Steffen. It made a lasting impression on the four-term lawmaker.

“I never realized my three-year probation actually was a life sentence,” the man, 27 years old at the time, told Steffen.

That time on probation stemmed from a physical altercation as a 17-year-old. The man, a constituent of Steffen’s, has had difficulty finding full-time employment since then because of his criminal record.

“Our criminal justice system is very good at establishing and using sticks,” Steffen says. “However, it rarely finds effective ways to use carrots.”

A new “carrot” approach is part of Steffen’s bipartisan legislation this year that would greatly expand expungement eligibility in Wisconsin. This would not be done by changing the types of crimes that can be expunged, but by ending two relatively strict and unusual aspects of the state’s laws on criminal records.

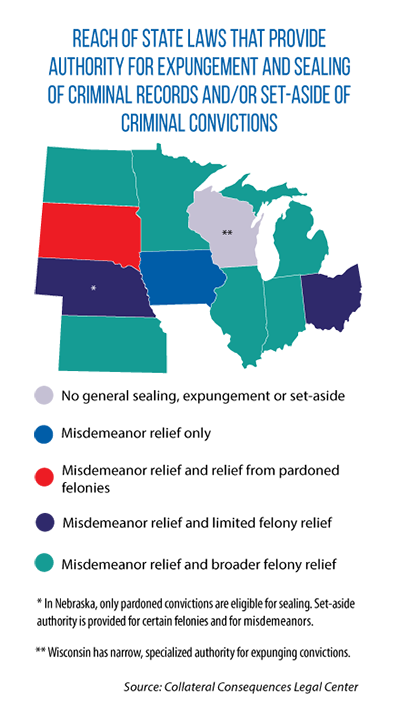

First, Wisconsin is one of only a few states with an age limit for expungement. An offender must be 25 years old or younger at the time he or she commits the crime in order to be eligible. Second, Wisconsin is the only U.S. state that requires expungement decisions to be made by the judge at the time of sentencing.

The proposed reforms would eliminate the age limit and allow for post-sentence expungement, an incentive for offenders to successfully complete their sentences and pay all fines, fees and restitution to the victim.

Steffen, a Republican, and Rep. Evan Goyke, a Democrat, first sought to expand expungement eligibility in 2017. Bills have failed to advance in previous sessions, but the proposal’s sponsors and supporters are more hopeful this year.

First, law-enforcement groups such as the Wisconsin Chiefs of Police Association and the Milwaukee Police Association are backing AB 69/SB 78. This session’s version of the bill includes an exception for police departments, which will still have access to a job applicant’s publicly expunged convictions.

Another key change: language requiring that a crime victim be notified if the offender is seeking expungement and be allowed to provide comments to the judge.

A primary goal of AB 69/SB 78 is to give Wisconsinites a greater chance at redemption, employment and a normal life.

But Steffen also points to another positive effect of changing the state’s laws on expungement: a greater pool of workers as the pandemic ends, the economy reopens, and some businesses’ report difficulty filling open positions. (Wisconsin’s unemployment rate in April was 3.9 percent).

“Because our legislation is retroactive, we have an opportunity to, in short order, add thousands of people to the workforce that were previously ineligible to participate,” he says.

“Expungement is a cost-free option of workforce development.”