Addressing rise in mental health needs, rebuilding public health systems loom as big challenges for states

Amid hopes that the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic is behind the Midwest, legislators heard from two policy experts in July who stressed the need for new investments in mental health and public health systems.

“[The] mental health tsunami is already upon us,” Debbie Plotnick, vice president for state and federal advocacy at Mental Health America, said during the Midwestern Legislative Conference Annual Meeting. The session was sponsored by the MLC Health & Human Services Committee.

Since April 2014, Plotnick’s organization has conducted 10 million online screenings. This early-identification tool is for individuals potentially in need of help for conditions such as depression and anxiety (the conditions for which people most commonly sought screenings). The COVID-19 pandemic led to a spike in those seeking assistance, and the screening results showed that the pandemic had a profound, negative effect on the nation’s mental health.

Since April 2014, Plotnick’s organization has conducted 10 million online screenings. This early-identification tool is for individuals potentially in need of help for conditions such as depression and anxiety (the conditions for which people most commonly sought screenings). The COVID-19 pandemic led to a spike in those seeking assistance, and the screening results showed that the pandemic had a profound, negative effect on the nation’s mental health.

Since 2014, 72 percent of the people seeking screenings were women, Plotnick said, and more than 63 percent were people ages 25 or younger. In particular, young people between the ages of 11 and 17 are experiencing high levels of depression and anxiety.

“What we’re finding is that nearly half of young people who are coming to Mental Health America are expressing thoughts of suicide every day,” Plotnick said.

One policy response for states: Invest more in school-based mental health. Such a strategy can help reach young people early on, avert a crisis and improve longer-term outcomes, Plotnick said. For example, about 70 percent of youths in state juvenile justice systems have a diagnosable mental health disorder, as do 64 percent of state and local jail populations.

Many new school-based initiatives are underway in the Midwest.

In Ohio, lawmakers have made a $675 million funding commitment in their two-year budget for schools to provide nonacademic, wraparound services to students. The most common service being provided is mental health.

Minnesota, meanwhile, funds one of the longest-running, school-based programs in the country. There, mental-health practitioners partner with local districts and come to the schools to provide direct care and treatment, assessments of student needs, and staff training.

During the MLC session, Plotnick recommended that states consider policies that replace police officers in schools with counselors. Her other ideas included:

• Ensure that recent gains in telehealth become permanent. “What we’ve learned from the pandemic is that telehealth is a tremendous tool,” she said. Options for states include allowing telehealth in programs such as Medicaid or requiring payments for this type of service by private insurers. This year, South Dakota became one of the first U.S. states to pass a law (SB 96) on telehealth; it made temporary rule changes from the pandemic permanent.

• Fund community-based, mobile mental health crisis teams that can respond to emergencies.

• Expand Medicaid coverage for new moms to 12 months after the birth of a child. In April, Illinois became the first state to secure a federal waiver for this kind of extension. (Coverage typically only extends to 60 days postpartum.)

• Increase the availability of mental health screening programs, especially for at-risk youths.

• Tap federal funds under the Families First Prevention Services Act to keep at-risk families together by providing services for mental health and substance-use disorders.

Action on public health

The pandemic also illustrated the danger of continued inaction in rebuilding public health systems, Sandra Melstad, a public health consultant and owner of South Dakota-based SLM Consulting, LLC, told legislators.

“If you’re an elected official, you’re part of the public health system,” she said.

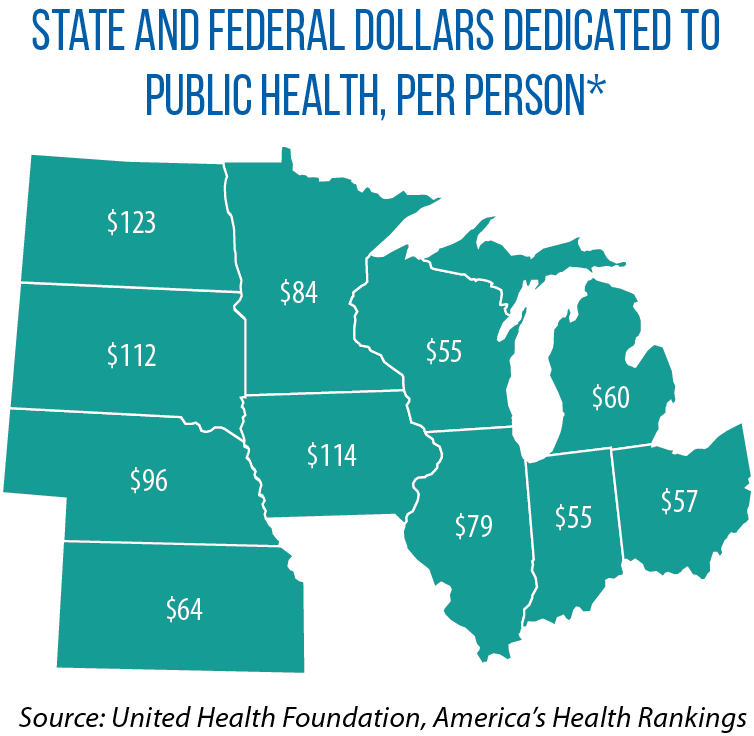

Less than 3 percent of the $3.6 trillion spent annually on health is directed to public health and disease prevention, she said, and prevention is being funded at the same level as in 2001 — an effective cut of 23 percent when inflation is considered.

She pointed to several consequences of this underfunding: shortages in public health workforces, and a lack of access to resources that help with disease prevention and preparedness.

According to Melstad, the pandemic also shed light on continuing public health inequities, an issue that demands legislators take a broader look at the many social determinants of health — and then address them.

She said other priorities for states should include strengthening the public health infrastructure and workforce capacity by investing in technologies that allow better tracking of future pandemics, as well as the prevention of chronic diseases, substance misuse and suicide.