Hit hard by pandemic, many women, minority and non-degreed workers still face labor-market challenges

The pandemic-related dip in jobs and economic output often has been referred to as the “she-cession” because of its disproportionate, adverse impact on female workers.

Economist Michael Horrigan told legislators in July that federal data on employment tell a slightly more nuanced story.

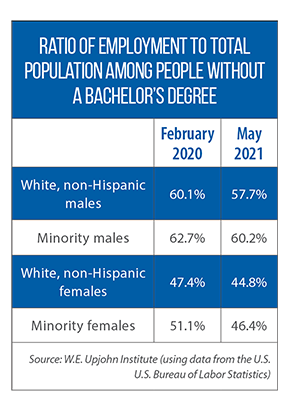

It’s a “less-than-B.A. recession,” he said at the Midwestern Legislative Conference Annual Meeting, “with significant impacts on women and minorities.”

It’s a “less-than-B.A. recession,” he said at the Midwestern Legislative Conference Annual Meeting, “with significant impacts on women and minorities.”

Likewise, many groups of workers without postsecondary degrees or credentials continue to struggle even as the U.S. economy grows.

“Those with less than a [bachelor’s degree] have had an especially difficult time regaining employment since April 2020,” Horrigan, president of the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, said during a session organized by the Midwestern Legislative Conference Economic Development Committee.

During the first few months of the pandemic (February to April 2020), overall employment declined by 22.2 million jobs. This drop was highly concentrated in lower-wage sectors and establishments — 64 percent of the nation’s total.

“Ten industries alone accounted for over half of those employment declines,” said Horrigan, noting huge losses in jobs related to hospitality, entertainment, travel, retail and child care.

Women have had a higher rate of job loss relative to their employment status, and in particular, minority women have been at a greater risk of labor market-related displacement and disruption. For example, as of February 2020, minority women represented less than 12 percent of employment; they accounted for nearly 21 percent of the people who lost jobs between February and April 2020.

“This is a really important lesson in terms of who got hurt by the pandemic,” Horrigan said.

Bouncing back for many displaced workers has not been easy.

As of June 2021, more than 42 percent of the nation’s population of jobless workers were “long-term unemployed.” This means they had been out of work and searching for a job for 27 weeks or longer.

“The labor market is changing in terms of skill requirements, automation,” Horrigan said. “These [long-term unemployed] are the folks who are going to have the hardest, long-term problems in the labor market.”

Minorities make up a disproportionate share of the nation’s long-term unemployed: 23.9 percent and 17.1 percent for minority males and females, respectively, as of May.

Horrigan suggested that policymakers also pay close attention to trends in the “near unemployed”: individuals who have been laid off, either temporarily or permanently, but are not yet searching for work.

This group is considered out of the labor force and not counted as unemployed.

“[Some] are coming back in,” he said, “or we hope they are coming back in.”

As of June 2021, nearly 7 million individuals who were out of the labor force reported that they wanted a job now. But they cited various factors — child care, family responsibilities, transportation, etc. — for not seeking work.

Among this group of the “hidden” or “near” unemployed, there is a disproportionate share of females without a college degree as well as minority females.

It is unknown how many of these workers will remain out of the labor force or for how long, Horrigan said. He urged legislators to focus on strategies that help bring them back to the workplace.