With more jobs requiring occupational licenses, states look to remove obstacles for formerly incarcerated

Sixty years ago, about one in 20 jobs required an occupational license. Today, it’s one in four.

Sixty years ago, about one in 20 jobs required an occupational license. Today, it’s one in four.

That trend has closed many employment and career opportunities for individuals with a criminal record because of another figure — 13,000, the approximate number of provisions in state law that serve as barriers to licensure, according to the National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction.

As lawmakers learned in July at a session of the Midwestern Legislative Conference Annual Meeting, states have begun to chip away at those barriers. These fair-chance licensing reforms have several objectives: Give individuals a greater chance at re-entry success, make them less likely to reoffend, and meet a state’s workforce needs.

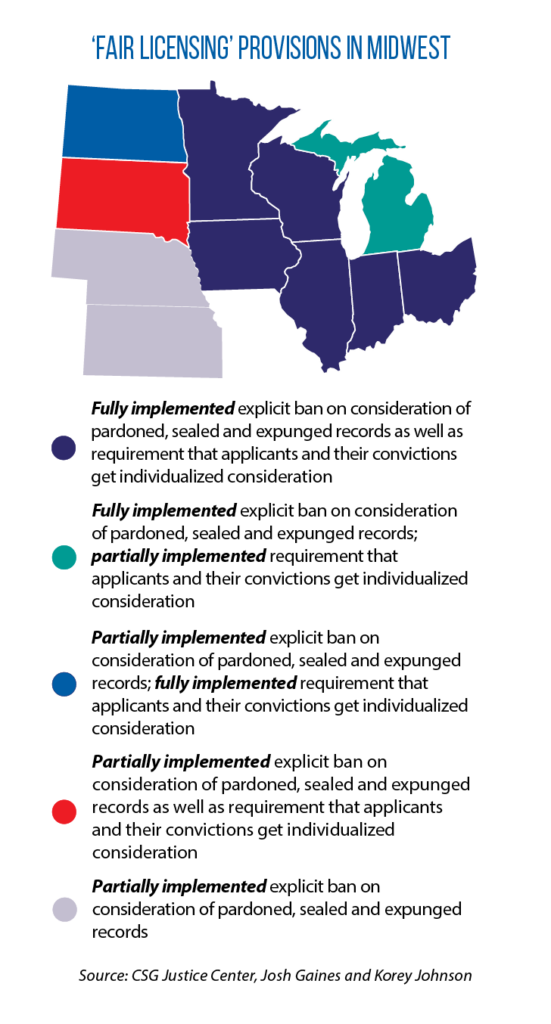

Organized by the MLC’s Criminal Justice & Public Safety Committee, the session featured presentations by Josh Gaines and Korey Johnson of The Council of State Governments’ Justice Center and Adam Diersing of the CSG Center of Innovation. Together, they briefed lawmakers on different ways to remove barriers to licensure.

For instance, Minnesota and other states have determined that certain low-level offenses do not pose a public safety risk. They now broadly prohibit such offenses from being considered in licensing applications.

In states such as Indiana, Kansas and Ohio, after a certain period of conviction-free years, individuals are less likely to have their criminal records stand in the way of securing a license. This is because of laws that reflect what the data show about the likelihood of recidivism: it declines significantly as more and more time passes from when the conviction occurred.

Another policy idea is to enact procedural protections at the back end of the licensing process. North Dakota and Ohio are among eight states that require a written explanation of specific reasons for conviction-based denials. This provides applicants with a record for challenge or appeal, and informs them of possible remedies. It also ensures that licensing bodies are properly applying the law.

On the front end, states can inform applicants about what licenses are possible. Indiana, Iowa, Nebraska, Ohio and Wisconsin provide pre-application determinations letting individuals know if their criminal records are disqualifying.

The hope is that these policy changes improve outcomes. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, 27 percent of formerly incarcerated individuals are unemployed. Figures are even higher for women and people of color. Formerly incarcerated Black women, for example, have a jobless rate of nearly 44 percent; that compares to 6 percent for Black women in the general population.