Illinois ties nuclear power to new pledge to be carbon-free by 2050

For states across Midwest, uncertainty remains over future of storing and shipping spent fuel

On Sept. 13, the 727 employees of the Byron Nuclear Generating Station were finally able to breathe a collective sigh of relief. That was the day the Illinois Senate passed SB 2408 and sent the measure to Gov. J.B. Pritzker, ending nine months of nail-biting negotiations.

On Sept. 13, the 727 employees of the Byron Nuclear Generating Station were finally able to breathe a collective sigh of relief. That was the day the Illinois Senate passed SB 2408 and sent the measure to Gov. J.B. Pritzker, ending nine months of nail-biting negotiations.

At stake for the plant’s workers were their jobs.

And for the entire state, the new law will shape Illinois’ energy future for decades to come.

It pledges a transition to 100 percent clean energy by 2050 and includes new requirements for different types of existing power plants. For example, municipal coal- and natural gas-fired plants must be carbon-free by 2045, private coal plants must have zero emissions by 2030, and private natural gas plants must reach this target by 2045. These plants will be shut down if the requirements are not met.

At the same time, the new law helps keep open the Byron facility, along with a second nuclear power plant, Dresden, in the Illinois town of Morris. It does so by including a $694 million state subsidy (paid for by ratepayers).

“They are our largest carbon-free generators,” Illinois Sen. Michael Hastings says of his state’s 11 nuclear reactors. “They power over 11 million homes. For them to close would be catastrophic to us reaching our clean energy goals.

“It would take us close to 30 years to replace nuclear plants with just wind and solar generation.”

Two years ago, Exelon announced that without a state subsidy, the company would retire its Byron and Dresden plants due to competition from cheaper, natural gas-fired plants. An independent consulting firm hired by the state in January 2021 confirmed that the plants could not remain economically viable without state support.

This is not the first time Illinois legislators intervened to keep some of Exelon’s nuclear plants open. In 2016, they provided $235 million per year so that two other facilities would remain running for a minimum of 10 years.

The idea of a second “bailout” for Exelon was going to be politically challenging regardless. Adding to the difficulty was a highly publicized political bribery case against ComEd, a former subsidiary of Exelon.

Nevertheless, due in large part to the nuclear fleet’s importance to broader environmental goals (it currently accounts for 90 percent of Illinois’ carbon-free energy), lawmakers reached a subsidy agreement during a special session in June.

However, disagreements over other parts of SB 2408 prevented its passage in the early summer months.

So the clock ticked as legislators, the governor and others continued negotiations. Meanwhile, Exelon said the Byron plant would run out of fuel and permanently shut down on Sept. 13.

In the 11th hour, disagreements were resolved, the legislation passed and Exelon announced it would refuel the plants.

The 727 employees at Byron, along with 791 employees at Dresden, could breathe easier. According to Hastings, the same goes for the whole state of Illinois. “Coming off the COVID-19 pandemic, the economic impact that would have occurred as a result of two to four nuclear plants closing would be devastating,” he says.

Radioactive waste at Midwest’s existing, decommissioned plants

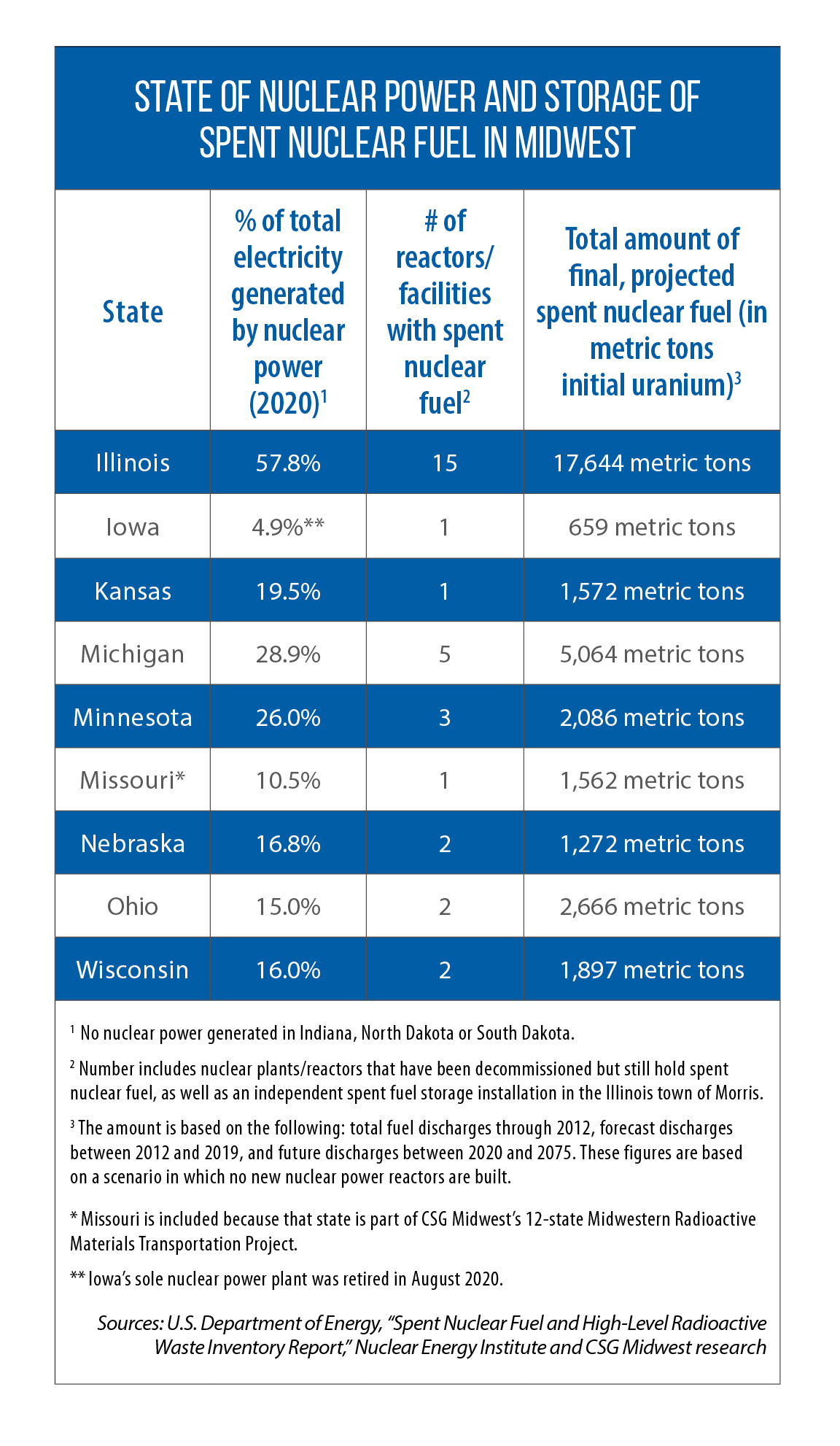

Nuclear energy plays a large role in the Midwest’s electricity supply. Currently, there are 17 nuclear plants in eight states and a total of 25 operating reactors.

In addition to these operating reactors, there are seven decommissioned reactors at six sites in five states.

These sites are at various stages in the decommissioning process. Duane Arnold in Iowa, for example, shut down just last year; decommissioning activities have not yet begun there. On the other hand, Illinois’ Zion and Michigan’s Big Rock Point sites are now fully decommissioned, with only spent nuclear fuel remaining on-site.

This fuel remains in dry casks at the shutdown sites because the federal government (responsible for all such waste under the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982) has not yet determined what to do with it.

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, the Midwest’s decommissioned and operating plants will eventually have an estimated 34,422 metric tons of spent nuclear fuel if the current reactors run through their licenses and no replacement reactors are built.

Ultimately, all of this fuel will need to be transported to one or several storage or disposal facilities.

Since the dry transportation casks that will likely ship this material are so heavy (usually more than 100 tons each), shipments will have to mostly take place via railroads. Heavy-haul trucks will transport casks from reactor sites to rail-loading sites if there are none located on-site.

To make these shipments safe, a complex web of regulatory requirements are in place and enforced by several federal agencies, as well as various state, tribal and local entities.

A central role for states

Regardless of the outcome of this year’s legislative debate in Illinois, there was going to be an impact on the transportation of radioactive materials in the Midwest.

If the Byron and Dresden plants had shut down permanently, the long process of decommissioning would have begun — including shipments of radioactive waste through the region.

When the two reactors at Zion Nuclear Power Station (located 40 miles north of Chicago) shut down in 1998, decontamination and dismantlement did not even begin until 2011. Final decommissioning activities at Zion were just finished this year.

These activities resulted in rail shipments totaling 3,881 rail cars and an additional 413 truck shipments of low-level radioactive waste from northern Illinois to a disposal facility in Utah They passed through Wisconsin, Iowa and Nebraska along the way. This included a highly technical shipment of a 17-foot-diameter, 225,000-pound reactor head.

Midwestern states and localities would have had to expect, and prepare for, similar activities if the Byron and Dresden reactors had shut down.

And states play a critical role in executing these radioactive waste shipments through the region.

They are co-regulators with the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission and U.S. Departments of Energy and Transportation. More broadly, too, state and local governments share the responsibility for protecting public health and safety. In addition, they are experts in local conditions — road conditions, requirements for inspections or escorts, key dates to avoid, or even the political landscape.

For these reasons, states help lead the planning of shipments of radioactive waste and spent nuclear fuel. This includes route identification, emergency preparedness, safety and radiological inspections, shipment monitoring and public information campaigns.

Because of the Illinois General Assembly’s passage of SB 2408, there will not be any new decommissioning activities in that state anytime soon.

However, a combined total of 35 metric tons of spent nuclear fuel will be discharged from the Byron and Dresden generating stations every year that they remain open.

The now-decommissioned Zion plant operated for more than 20 years, and more than 1,000 metric tons of spent nuclear fuel remain on-site.

Future of spent-fuel storage

Where will all of this spent nuclear fuel from the Midwest go?

The answer is no longer Yucca Mountain in Nevada; the U.S. government stopped that project in 2009. More recently, private sector-led proposals have been advancing.

In September, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission issued a license to Interim Storage Partners for construction of a site in Texas. This private, interim storage facility is authorized to initially hold 5,000 metric tons of spent nuclear fuel and can add capacity later. An NRC decision on a second proposed facility (this one by Holtec International for a site in New Mexico) is expected in January.

But just days before the NRC issued Interim Storage Partners’ license, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott signed HB 7.

This new law bans the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality from issuing permits for facilities that store nuclear fuel. It is unclear if this state law will matter to the federal government and Interim Storage Partners in the end, but legal challenges are likely if the project proceeds. (State and local objections in Nevada are what led to the end of Yucca.)

So as Illinois and other Midwestern states continue to rely on nuclear power, the problem of finding a place to store the waste remains unresolved.

The Council of State Governments partners with the U.S. Department of Energy on the Midwestern Radioactive Materials Transportation Project, which helps states prepare for and execute shipments within their jurisdictions. Mitch Arvidson manages the project for CSG Midwest.