In search of affordable housing

Shortages are impacting rural and urban communities in the Midwest; tools for states include housing tax credits, assistance for low-income renters and incentives for builders

In his home state’s larger urban areas, Kansas Sen. Rob Olson says, affordable housing units are going away. Homes get bought and flipped, prices rise, and lower-income people are left with fewer options.

In many rural communities, houses have been getting torn down and not getting replaced for decades. That means higher property taxes on the homes that remain, and a smaller housing stock to attract and accommodate new residents.

“These are our workers, and now they don’t have a place to live,” Olson says.

It adds up to a statewide problem that he and other Kansas legislators are studying and acting on.

This year, they passed a measure to spur more housing development in some of the state’s smaller downtown communities. Many other measures are being worked on in advance of the 2022 session.

“Kansas has multiple issues [to address],” Olson says.

Across the country, in fact, this has been an unusually active year for state policy on housing. Of particular interest: strategies that increase the availability of affordable housing.

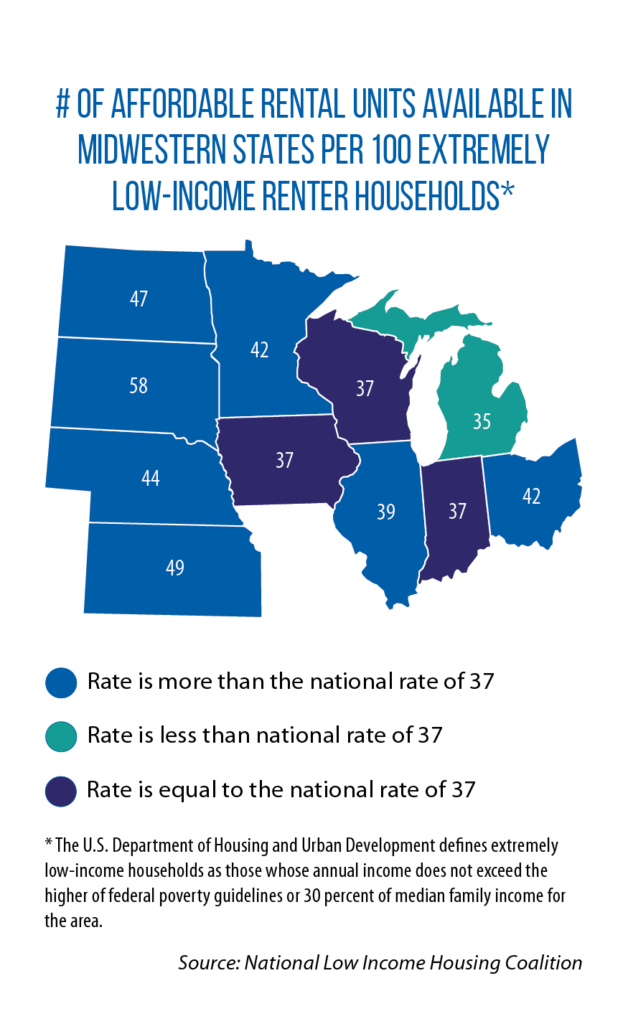

In every state, there are many more low-income renters than affordable rental units. And this problem has worsened in recent years.

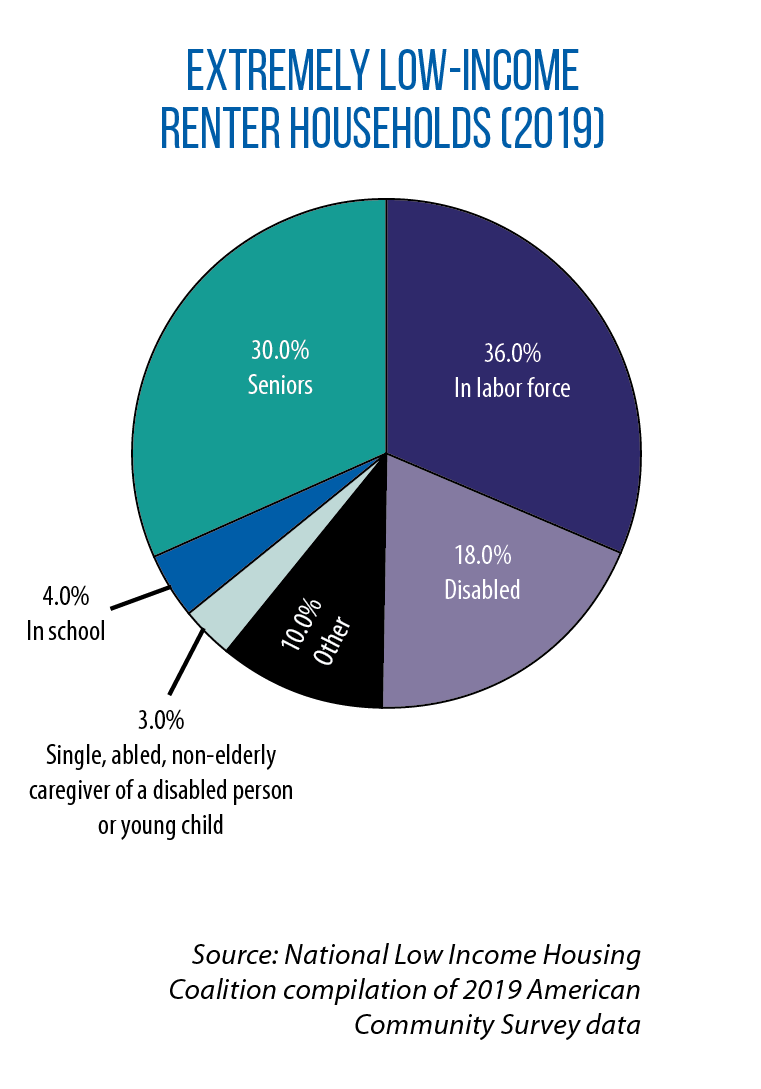

According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, as of March 2021, almost 14 million renter households with incomes of less than $50,000 nationwide had lost employment income due to the pandemic, and “about a third of all households were having trouble paying for usual household expenses.”

These hardships have fallen disproportionately on people of color as well. While 39 percent of White adults lost income during the pandemic, 49 percent of Black adults and 58 percent of Hispanic adults did.

“The housing crisis has tentacles that reach into every corner of our society,” Elliott Gaskins, managing director of Share Our Strength, a nonprofit organization fighting hunger and poverty, said in September during a webinar hosted by the Aspen Institute.

“If you don’t have a home, you don’t have a kitchen to prepare meals for your family. If you’re worried about eviction, the mental toll that takes on your family is long-lasting.

“If you are doubling up in homes with families, then the risk of things like COVID and other health issues dramatically [magnifies].”

HOUSING, THE AMERICAN RESCUE PLAN AND STATES

This year’s U.S. American Rescue Plan Act allocated $43 billion to states in mandatory funding for housing programs such as emergency rental and homeowner assistance, housing vouchers and help for the homeless.

Under this year’s HB 167, Ohio used $465 million of its allocation for emergency rental and utility assistance.

Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds and Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer each announced plans to allocate $100 million of their states’ share of ARP money to affordable housing programs.

Whitmer’s proposal, which needs legislative approval, would put $100 million into the Michigan Housing and Community Development Fund. That fund is “designed to fuel strategies leveraging public and private resources to meet the affordable housing needs” of low-, very low- and extremely low-income households.

According to The Des Moines Register, Reynolds will split $100 million among several programs:

• $65 million to bolster an existing housing tax credit;

• $10 million for the Homes for Iowa program, a nonprofit group that employs inmates to build affordable housing;

• $5 million for pilot programs that promote home repairs across Iowa as well as homeownership among minority groups; and

• $20 million for downtown housing in cities with under 30,000 people.

Under that new $20 million grant program for smaller cities, Iowa hopes the state dollars spur the development of upper-story housing in existing buildings, as well as the revitalization of vacant schools and other buildings.

Likewise, Kansas’ SB 90 (initially sponsored by the committee on which Sen. Olson serves as chair) is targeting more housing development in small communities’ downtowns.

The measure, signed into law in July, expands the reach of an existing program that allows certain smaller-sized communities to establish rural housing incentive districts — a type of public subsidy (tax increment financing) for developers. Under SB 90, eligible projects now include the renovation of buildings at least 25 years old for housing above ground-floor retail.

According to Olson, this new law is just one piece of a multifaceted policy response needed to address Kansas’ housing challenges. Bills being developed for next session include aid for first-time buyers, additional state funding for affordable housing programs, and new initiatives for modular housing.

NEW HOUSING INVESTMENTS IN ILLINOIS, PROPOSALS IN MICHIGAN

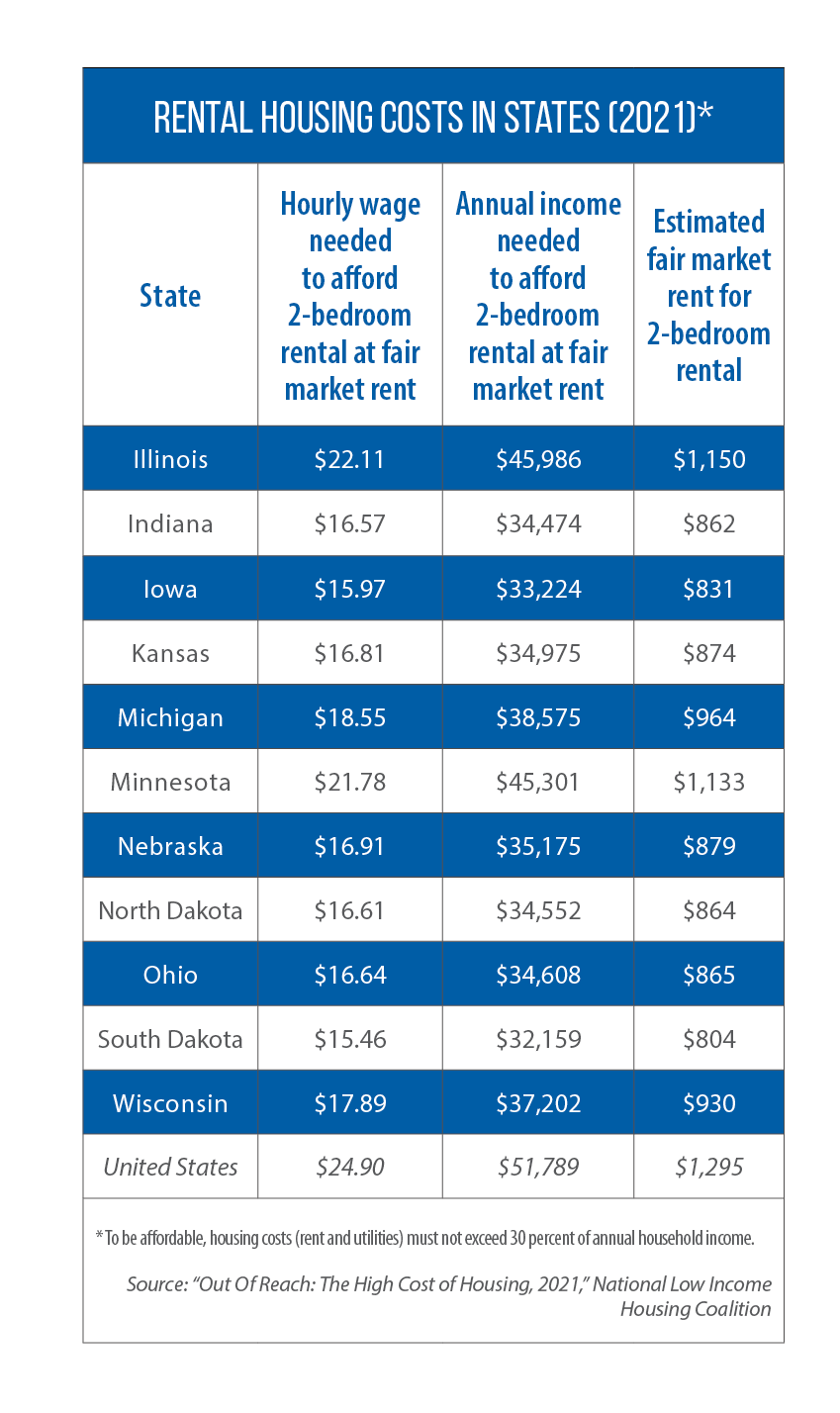

What is “affordable housing”? The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development defines it as costing no more than 30 percent of a household’s gross income.

The lack of it is not a new problem, as evidenced by the many programs that states already have in place — from rental assistance and emergency or transitional housing for those at risk of becoming homeless, to financial incentives for builders, to tax breaks for the elderly or disabled veterans.

At the federal level, the Low Income Housing Tax Credit targets affordable housing investments and development. It makes such projects more attractive by providing credits equal to either 4 or 9 percent of the project’s costs for 10 years.

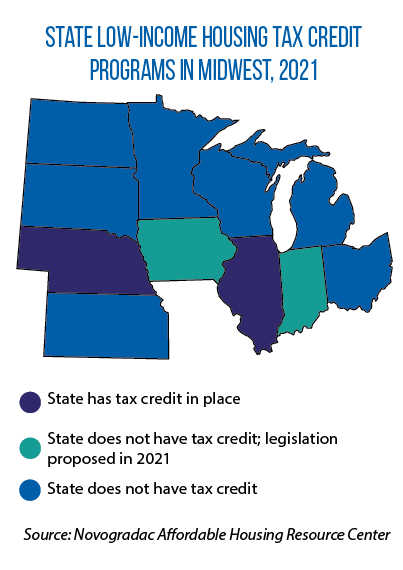

States are allocated a fixed amount of credits based on population, and also can implement their own versions of the credit to provide yet another extra boost.

In the Midwest, Nebraska did so in 2016 (LB 884), and Illinois extended its Affordable Housing Tax Credit program with this year’s passage of HB 2621.

“Illinois, like a lot of states, ends up leaving many of those lower credits on the table because they’re more difficult for developers to make them work,” Illinois Rep. Will Guzzardi says. “Creating a state equivalent of those federal tax credits has been a legislative goal for a few years. Our hope is to use this as a demonstration of the value of this kind of program.”

Under the new law, over the next four years, Illinois will use $75 million annually in newly available federal dollars for a COVID-19 Affordable Housing Grant Program.

That money will support rental-housing construction and rehabilitation in areas most impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Guzzardi, the bill’s sponsor, says it will give “an extra shot in the arm” for developers to secure funding and move ahead with projects.

Another provision in HB 2621 gives property tax breaks for qualifying new or rehabilitated multifamily buildings with affordable housing units. It does so by reducing the property’s assessed value.

For example, the owner of a multi-family unit can invest in improvement to the dwelling and get a tax break — so long as he or she keeps the rent affordable.

For new construction, buildings with at least 15 percent of their units as affordable can get a 25 percent reduction for 10 years. Those offering more than 35 percent of their units as affordable can get a 35 percent reduction.

This should help slow the loss of affordable housing in urban neighborhoods, including his own, Guzzardi says.

Meanwhile, almost a dozen tax-related affordable housing bills are pending in Michigan. Ideas include:

• permitting local governments to establish “attainable housing districts” in which property owners with lower income renters would get partial tax exemptions for one to 12 years (HB 4647 and SB 362);

• giving employers an income tax credit for contributions to affordable housing trust funds or for direct housing assistance to lower-income workers (HBs 4649 and 4650 and SBs 360 and 361);

• expanding the use of Neighborhood Enterprise Zones (HB 4646 and SB 364) and creating a Residential Facilities Exemption (HB 4827 and SB 422) to provide property tax breaks to affordable housing developments within districts created by local governments; and

• allowing local governments to create Payment In Lieu Of Taxes programs for developers building or rehabilitating affordable housing (SB 432).

‘ALL PART OF SOLUTION’

Indiana and Michigan are among states now working on formal housing plans, while Kansas has launched its first statewide assessment of housing needs in 27 years. It is scheduled to be completed by December.

Michigan’s most recent housing-needs study was done in 2019, and it set the stage for a housing plan due in early 2022, says Gary Heidel, acting executive director of the Michigan State Housing Development Authority.

Seventeen “solution groups,” encompassing construction, finance and other housing-related interests, are now taking deep dives into priority areas; at the same time, a group of state agencies has been soliciting public feedback to learn what people across the state are seeing in their communities.

“The idea is that it’s not just a housing plan, but a way to address the entire [housing] industry so we can all be part of the solution,” Heidel says.

Before year’s end, Indiana plans to debut a new a web-based housing “dashboard” providing real-time information on existing and needed housing stock sortable by category and location, says Mike McQuillan, the Indiana Housing and Community Development Authority’s director of industry and government affairs.

“This tool will serve as a great resource for not only our state’s homebuilders, but all stakeholder groups, local officials, and others as they use this information to make decisions for Indiana’s future,” McQuillan says.

Indiana legislators made affordable housing a topic for the General Assembly’s summer study session.

Sen. Shelli Yoder, who suggested the topic after hearing from constituents, says she’s already working to draft legislation for the 2022 session based on the study’s recommendations. People try hard to live within their means, but “when there is no housing available, that makes that very challenging,” she says.

“Hoosiers are finding that affordable housing is simply not available and that creates quite a strain.

“There is no silver bullet. This has to be a multi-pronged approach,” she says.

South Dakota legislators also made housing an interim session study topic.

While a matter of local control, zoning codes are coming under increasing state scrutiny as they have sometimes outlawed duplexes or four-plexes, live/work units, courtyard buildings and accessory or auxiliary units (for example, coach houses or “granny flats”) in favor of single-family lots.

California allowed accessory units by law when AB 2299 was enacted in September 2016. This year, a new state law (SB 9) effectively ends single-family zoning by allowing duplexes or second units to be built on single-family lots and permitting the bisection of those lots into new lots of at least 1,200 square feet, each of which could host a duplex.

While no similar legislation is on the Midwest’s horizon, some officials are willing to look at zoning as an element of solutions to affordable housing.

Iowa’s Empower Rural Iowa program offers $10,000 housing grants to qualifying municipalities, which then work with Iowa State University Extension to examine their housing needs.

Liesl Siebert, rural community revitalization program manager for the Iowa Economic Development Authority, which oversees the program, says some of the 20 grant winners so far have used those funds to hire specialists to rewrite or update their zoning codes.