Capital Closeup: A reset on the balance of powers

Legislative action in 2021 means more checks on governors during times of emergency

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about unprecedented changes in nearly all aspects of social and civic life, and the functions and policies of state government have been no exception.

Never in the nation’s history, for example, had all 50 states been under emergency orders at the same time — until 2020.

Requirements of residents to stay at home and limit the size of gatherings.

The forced closures of businesses and schools.

Mask and vaccine mandates.

These and many other pandemic-related decisions fell largely to the executive branch and governors, who had the legal authority to issue those emergency orders. As the pandemic dragged on, though, questions about this kind of unilateral decision-making crept into the public discourse, and into the halls of state capitols.

“Clearly, COVID has been one area where legislatures have in a fairly direct way tried to rein in the executive branch, in a way that you have not seen much in the last generation,” says Peverill Squire, a professor of political science at the University of Missouri and leading expert on state legislatures and the legislative institution.

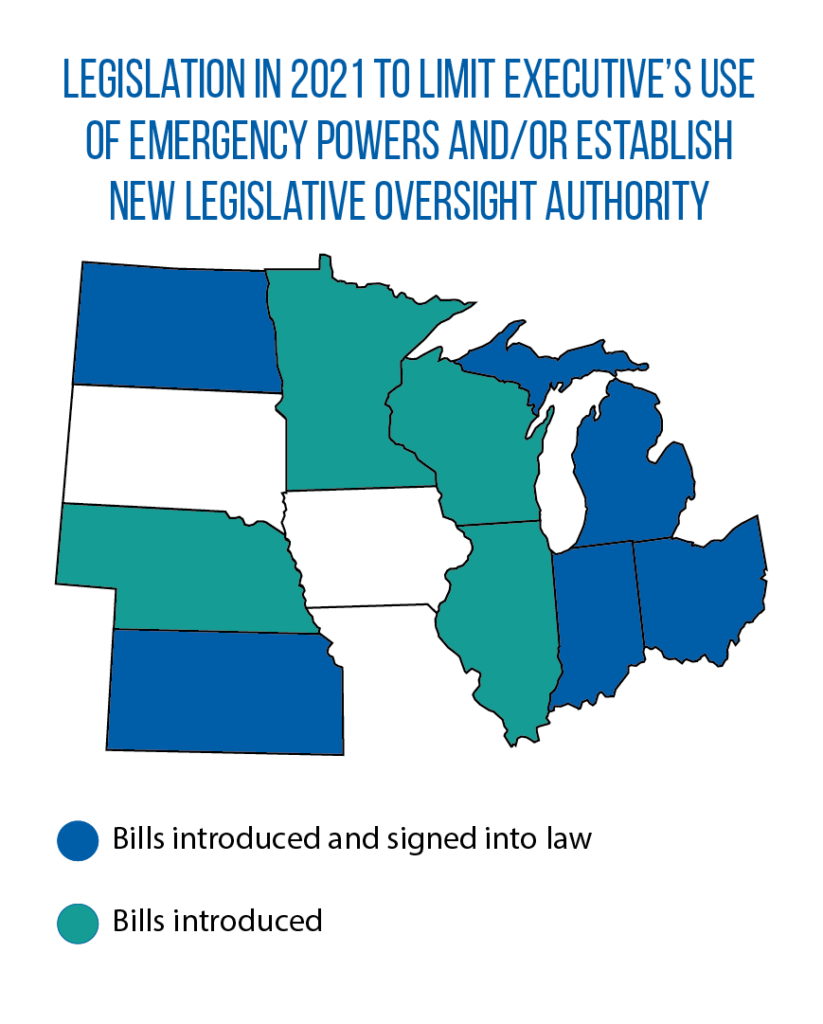

In this region, in every state except Iowa and South Dakota, bills were introduced in 2021 to address concerns about the length and breadth of governors’ emergency orders and powers, as well as the inability of legislators to check or oversee those powers. Measures were approved in nearly 20 U.S. states, including Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, North Dakota and Ohio.

“We have two different things going on simultaneously over the last 18 months,” Squire says. “On one hand, we’ve seen these battles between the executive and legislative branches involve some clearly partisan battles between different parties holding different institutions.

“And on the other hand, we’ve also seen institutional differences of legislatures reacting to executive action on COVID, even though the same party controls both the governorship and both chambers of the legislature.”

That mix certainly has been true in the Midwest.

The Republican-led legislatures in Indiana, North Dakota and Ohio took steps to control the powers of Republican governors. In Kansas, a compromise was reached in a state where partisan control is divided. And in Michigan, where control also is split, legislators teamed up with some citizens in the state (via the indirect initiative) to change the power dynamic. Here is a closer look at the new laws in those five Midwestern states, as well as how they came to be.

Ohio: ‘It cannot be indefinite’

In times of crisis or emergency, Ohio Sen. Robert McColley says, the executive branch needs the authority to act decisively and to be nimble.

“But it absolutely cannot be indefinite,” he adds. “If it’s indefinite, then the executive branch is essentially occupying two branches of government and becoming the legislature.”

Since the early days of the pandemic, McColley began thinking about ways to find a better balance in his home state: an executive branch with enough power to protect the public health in times of emergencies, but with adequate legislative limits and oversight in place.

“The problem began when it became apparent that not only was the executive branch acting outside of what many of us believed its statutory or constitutional authority to be, but that we didn’t have an apparent end or plan in sight for when things would return back to normal,” he says.

His solution was SB 22, a bill that became law in March after the General Assembly successfully overrode a veto by Gov. Mike DeWine.

“We are not limiting the governor or the director of health from issuing any orders,” he says. “We are making it very clear that everything that the legislature is able to do is going to be after the [orders are in place].”

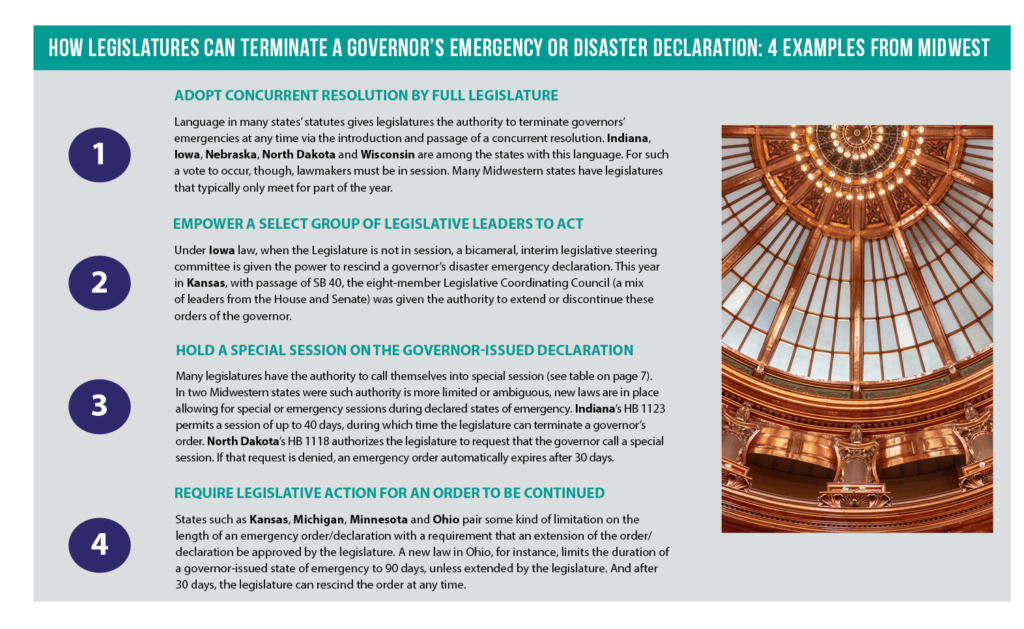

Under the new law, the duration of any governor-issued state of emergency is limited to 90 days, unless the legislature votes to extend it. And after 30 days of an emergency order being in place, legislators can terminate it. The governor is barred from reissuing a state of emergency for 60 days after its expiration or termination, unless the legislature adopts a concurrent resolution in support of such a decision.

“The bill is meant to restore the natural balance and separation of powers in that the governor, or any of his departments, can do only what their legislative scope of authority is,” McColley says.

During a state of emergency, too, an Ohio Health Oversight and Advisory Committee (made up of select senators and representatives) now has the authority to oversee actions taken by the governor and Department of Health. In his veto message, DeWine said SB 22 “jeopardizes the safety of every Ohioan,” and called attention to another part of the law that generally blocks local health departments from banning mass gatherings or closing schools. (Now, these departments can only close a specific school with verified positive cases of a dangerous communicable disease.)

“[It] strikes at the heart of local health departments’ ability to move quickly to protect the public from the most serious emergencies,” DeWine wrote.

Michigan: Indirect initiative tilts balance of power

In neighboring Michigan, the Emergency Powers of Governor Act had been in place for more than a half century. The 1945 law granted broad powers to the executive to declare an emergency and to “promulgate reasonable orders, rules and regulations as he or she considers necessary to protect life and property.”

Until last year, this decades-old statute received scant attention.

“Then [it] became incredibly relevant on the most important issue of the time,” says Matt Grossman, director of the Institute for Public Policy and Social Research at Michigan State University.

In an attempt to stem the spread of COVID-19 early in the pandemic, Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and the state Department of Health and Human Services used their powers to issue stay-at-home orders and close businesses.

Opposition to some of Whitmer’s actions grew in the Republican-led Legislature, and an effort to repeal the Emergency Powers of Governor Act began.

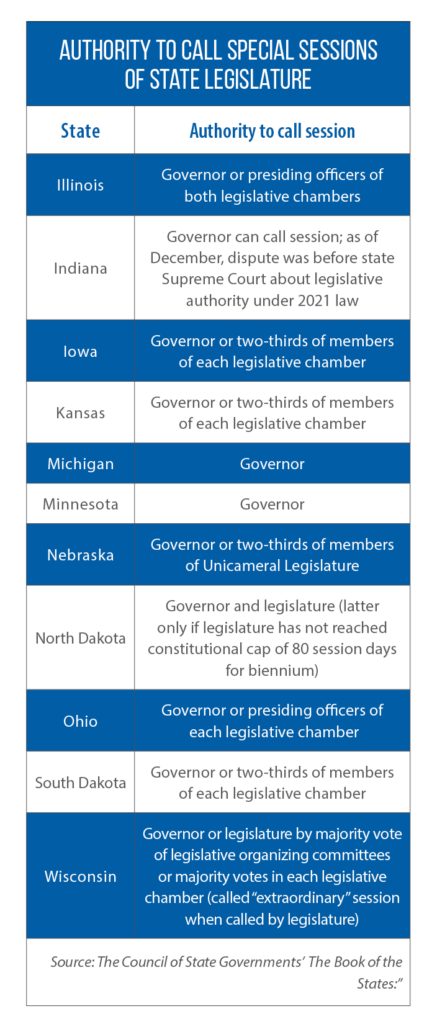

As Grossman notes, legislators in Michigan had a somewhat unique institutional tool available to them: the indirect initiative. Get enough citizens to sign a petition seeking a new law (or, in this case, the repeal of any existing one), and the Legislature can make the change via a simple majority vote. The governor has no veto power over an indirect initiative.

“It was envisioned more as something that would come from outside the Legislature,” Grossman says. “Then the Legislature would get to decide on it, and it has been used in that way [in the past].”

In this case, according to Grossman, it was more of a legislative-led effort.

“I’m not trying to say that the complaints [weren’t] legitimate, but I just think it wasn’t only about a general encroachment of the governor’s power,” Grossman says about how the institutional battle also reflected partisan division in Michigan.

By July, enough valid signatures had been collected to send the indirect initiative to the Republican-led Legislature. From there, it took less than a week for lawmakers to repeal the 1945 law. In Michigan, Grossman says, another factor in the recent power struggle between the legislative and executive branches is term limits, where lifetime service is capped at three two-year terms in the House and two four-year terms in the Senate.

“You don’t have any long-serving legislators, and they might feel that they are losing control over state government,” he explains. “It’s less about the governor specifically and more just about the growth of state governments. There are huge departments making all kinds of decisions, combined with a legislature with less experience. You’re going to have that feeling that the administrative apparatus is making decisions without much input [or oversight].”

Kansas: Compromise results in new law on disaster declarations

Kansas is one state where the two branches of government were able to reach a compromise on how to handle emergency declarations.

Under the agreement (SB 40), reached in March, Democratic Gov. Laura Kelly’s statewide disaster declaration was extended for at least an additional two months. But the measure also ultimately granted the power to end disaster declarations to the Kansas Legislative Coordinating Council, a joint committee of the state’s top legislative leaders.

The law stipulates that after an initial 15-day state of disaster emergency period, the authority to extend such a declaration rests with the council. An affirmative vote of five of the eight members is required for an extension, which can last up to 30 days. (There is no limit on how many times the council can vote to extend the state of disaster.)

In June, Kelly sought an extension through at least August; legislators denied her request. The disaster declaration was over in Kansas.

Leaders in the Republican-led Kansas Legislature applauded the modifications to the state’s Emergency Management Act, saying they ensured institutional checks and balances on the governor’s power. In a statement issued after signing SB 40, Kelly noted that the measure had “provisions that I do not support and that could complicate our emergency response efforts.” However, she said the two-month extension of the disaster declaration was critical to managing the pandemic.

Indiana: Legislature seeks power to call special sessions in emergency

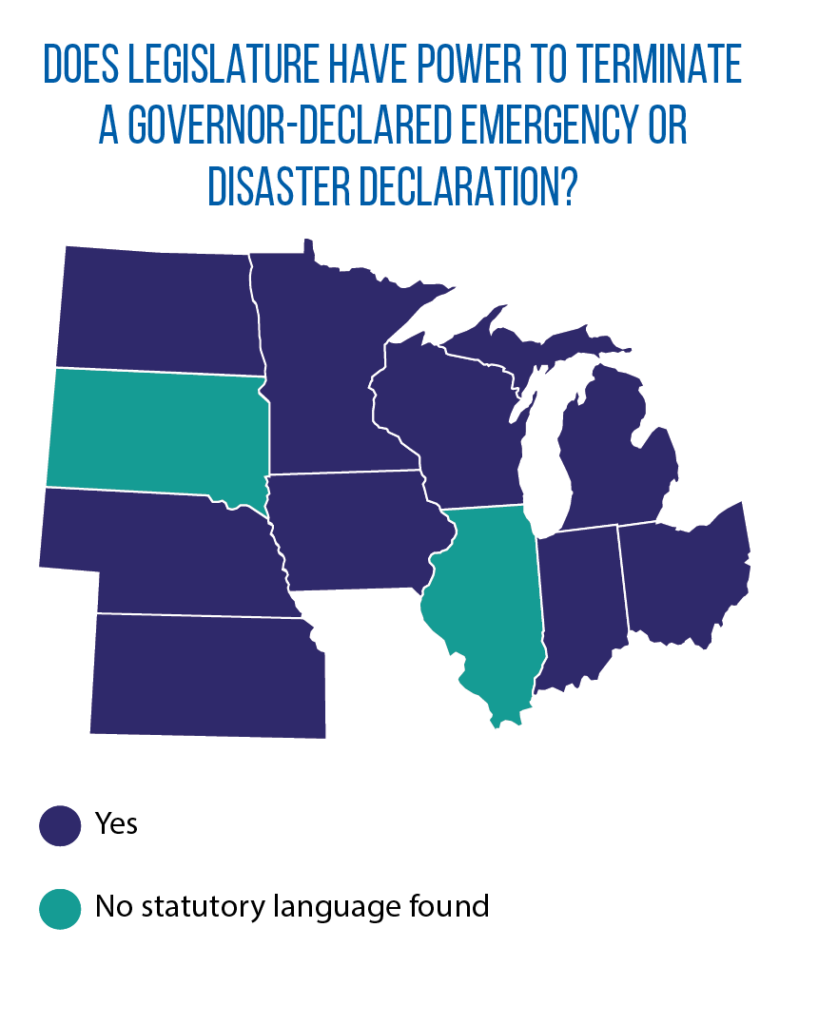

In the Midwest, most state legislatures have the statutory authority to terminate a governor’s emergency declaration, either at any time or after a certain prescribed amount of days into the emergency order.

This is typically done with passage of a concurrent resolution. But what if the legislature is not in session?

In this region, most state legislatures only meet for part of the year. One option for these out-of-session periods: give the power to end emergency orders to a select legislative committee, an approach used in states such as Kansas and Iowa.

A second option is for the legislature to call itself into special session. Such authority is common in states, but not universal. The question of special-session authority led to a constitutional battle in Indiana between the Republican governor and the state’s part-time, Republican-led legislature.

Passed in April, HB 1123 allows the General Assembly to convene in a 40-day session during a declared state of emergency. In order to do so, the Legislative Council (made up of 16 legislators) would first need to adopt a resolution; only issues stated in the resolution could then be considered. During this session, lawmakers could terminate a governor’s emergency order.

A veto by Gov. Eric Holcomb of HB 1123 was successfully overridden by the General Assembly.

Holcomb then challenged the law in court, arguing that Indiana’s Constitution only gives the governor, not the legislature, the power to call special sessions. In October, a Marion County Superior Court judge sided with the legislature, but the dispute ultimately will be decided by the state Supreme Court.

North Dakota: ‘Time for legislature to weigh in’

North Dakota also has a part-time state legislature, where lawmakers typically meet once every two years. The number of session days is limited to 80 per biennium. So even though the state’s Disaster Act of 1985 allowed the legislature to terminate a governor’s emergency or disaster declaration, there was an institutional problem for this branch of government: the declaration could be in place for a long time before the next scheduled session.

“I sincerely doubt quite honestly that when that change was made in 1985, anyone thought one of these [declarations] would go for months and months and months on end,” Rep. Bill Devlin said earlier this year during floor debate on HB 1118, which he sponsored.

Signed into law in April, the bill includes two significant changes to the North Dakota Disaster Act.

First, a public health-related emergency declaration by the governor is limited to 60 days. The legislature then would have the power to rescind or extend the state of emergency beyond 60 days. Second, whenever a state of emergency is issued, legislative leaders could request that the governor call them into special session. If the governor fails to call special session within seven days, an emergency order automatically expires after 30 days.

If the special session is held, the legislature could end, rescind or modify the emergency order.

“I think the governor does need to have the ability to declare an emergency,” North Dakota. Sen. Dick Dever says. “But after 30 days, I think it’s not an emergency anymore. There’s time to weigh in with the legislature and determine what the path forward should be.”