Capital Closeup: Multi-member legislative districts: Harder to find, but still in use in states such as North Dakota and South Dakota

At one time, multi-member districts were a common feature of representation in U.S. state legislatures. Voters would elect two, three, four, or even five or more legislators to represent them. In the 1970s, for instance, a single legislative district in Indiana had 15 representatives. And up until the 1980s, every Illinois resident had three state representatives.

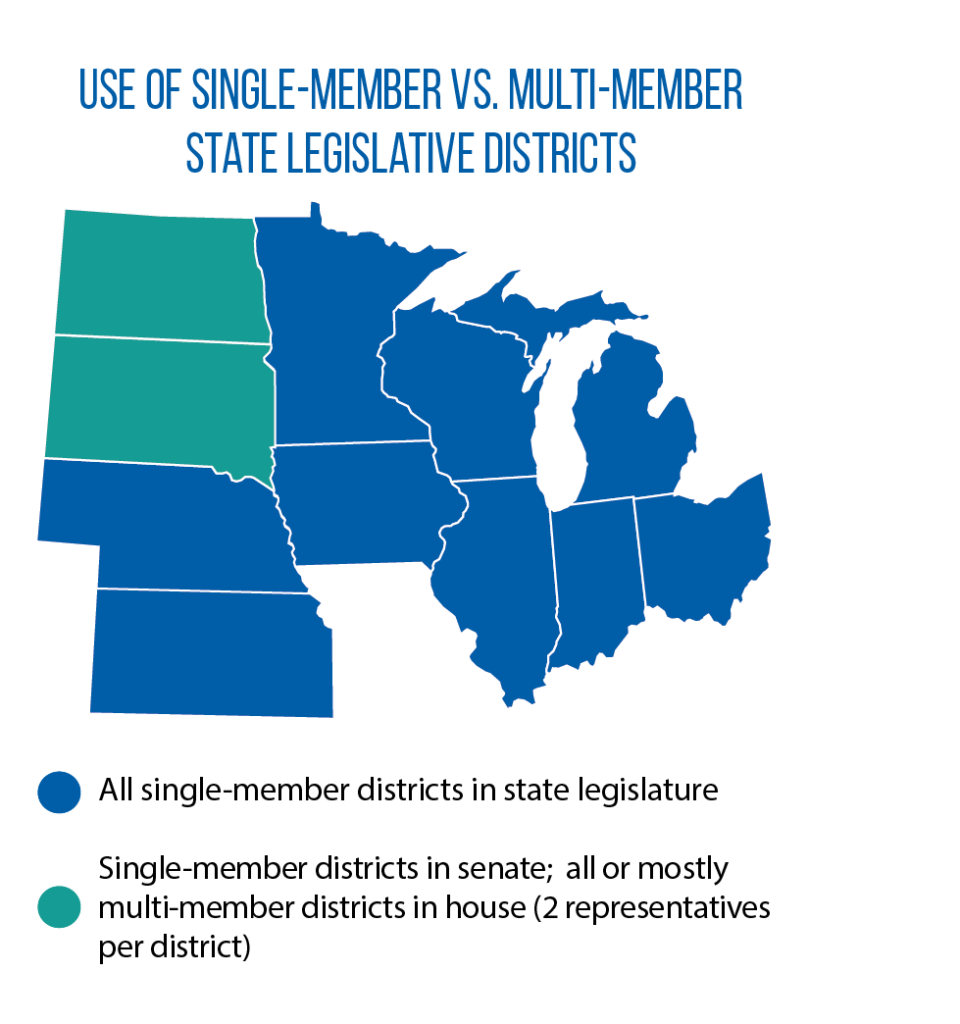

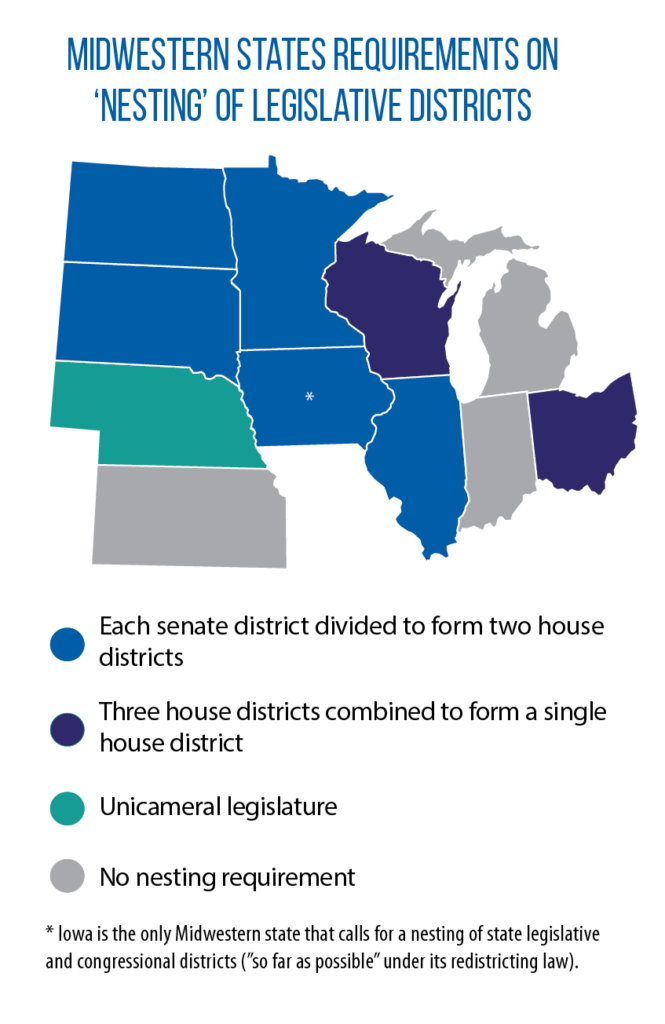

Over the past half century, these kinds of variations have largely disappeared from the nation’s electoral landscape: Most states now only have single-member legislative districts. Exceptions remain, however, including the continued use of multi-member districts in North Dakota and South Dakota, where one legislative district typically includes one senator and two at-large representatives.

It’s an arrangement that can lead to more orderly redistricting maps, simplify election administration, and allow legislators within a shared district to work together on local issues of concern.

But some unique considerations also come into play when a state’s political map gets redrawn every 10 years.

A change in North Dakota

This year, the North Dakota Legislative Assembly created four single-member House districts in two areas of the state with Native American reservations. It did so by creating sub-House districts in two separate Senate districts.

This split will prevent the votes of Native Americans from being diluted in a larger, multi-member district, and increase the chances of individuals from the Fort Berthold and Turtle Mountain reservations being elected to office.

Lawmakers approved this new plan during a special session in November.

Preceding that session were extensive deliberations by the joint legislative Redistricting Committee, briefings from legislative staff, and testimony from members of the public. That testimony included pleas from the tribal nations and Native American rights groups to establish single-member sub-districts.

Legislators learned, too, that the state may be legally bound to create them.

Over the past 10 years, population numbers on the Fort Berthold and Turtle Mountain reservations increased, and now exceed what would constitute a majority of votes in a House sub-district.

This threshold has been critical to courts in determining whether a state’s use of multi-member districts contravenes U.S. law.

“The overriding consideration of the Redistricting Committee and members of the Legislative Assembly was our belief we would be in violation of the federal Voting Rights Act if we did not split the districts,” says Rep. Bill Devlin, who served as chair of the committee.

‘Protect minority rights’

Section 2 of this 1965 federal law bans electoral practices that minimize the voting strength of racial or language minority groups. One of the results of this prohibition: the fall of multi-member districts because of their tendency to dilute the votes of minority citizens.

Across the country, a series of legislative-initiated or court-ordered changes occurred following enactment of the Voting Rights Act. (Starting in 1967, too, the U.S. Congress began requiring single-member districts in the U.S. House.)

South Dakota preceded North Dakota in establishing single-member House districts in specific areas of the state. It first did so after the 1990 Census, carving out two sub-districts “in order to protect minority rights.” There were subsequent legislative attempts to return to all multi-member districts, including adoption of such a plan in 1996. It was overturned by the state Supreme Court on the grounds that a mid-decade redrawing of the maps was unconstitutional.

In the next decade, South Dakota found itself at the center of a much-watched case involving redistricting and the Voting Rights Act — Bone Shirt v. Hazeltine.

Alfred Bone Shirt and others challenged the state’s legislative map in federal court, saying that the votes of Native American voters had been packed into a single Senate district. Bone Shirt prevailed, and a new court-drawn map included creation of an additional sub-House district with a majority Native American population.

“It increased Native American representation by one member,” says Bryan Sells, a civil rights lawyer who worked on the Bone Shirt case. “It’s not a lot, but it’s important to those voters. It gives a little greater voice and a seat at a table to an important constituency that has been historically discriminated against.”

Today, like North Dakota, South Dakota has a handful of single-member, sub-House districts. Still, multi-member House districts remain the norm in those two states, while non-existent in most others.

Could multi-member districts become more prevalent again?

Some advocates for changes in election law hope so, albeit in a different form that they say would actually increase minority representation. Under the proposed Fair Representation Act (HR 3863) now before Congress, multi-member U.S. House districts would be used in every state with more than one representative. If implemented along with proportional ranked-choice voting, proponents say, multi-member districts would lead to a greater diversity of candidates, including minorities, winning office.

Capital Closeup is an ongoing series of articles focusing on institutional issues in state governments and legislatures.