With need for nurses never higher, states mull short- and long-term fixes

States are boosting pay to retain workforce over the short-term; longer-term solutions are also being considered — from laws on working conditions to new scholarship programs

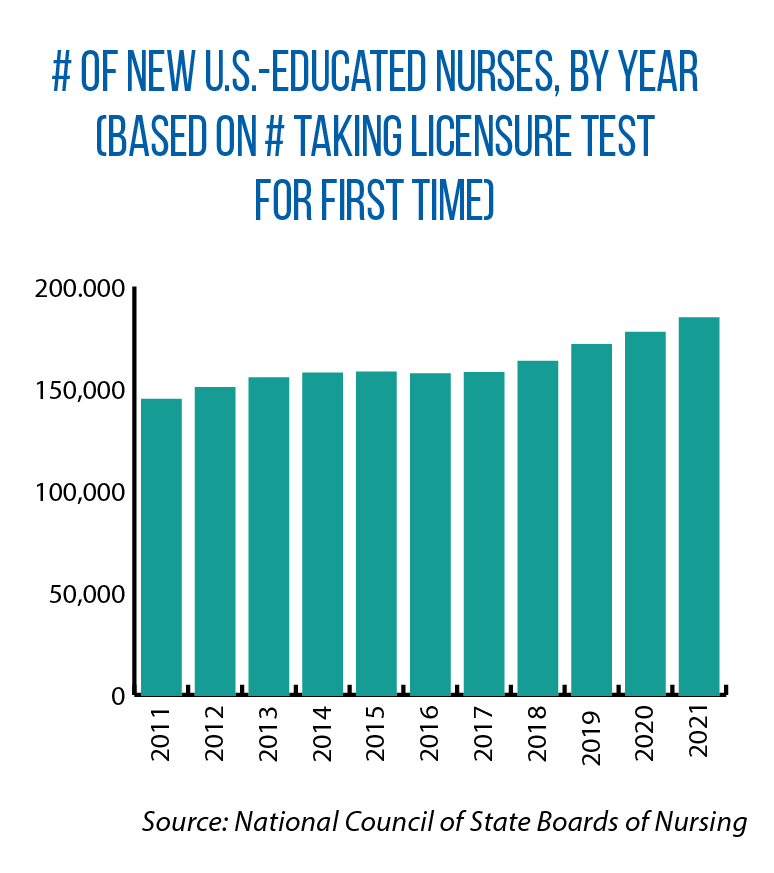

Never in the nation’s history have there been more registered nurses. And in 2021, the pool of new nurses entering the profession (as measured by the number of individuals taking the licensure test) reached 184,500 — a 17 percent increase from five years ago, according to the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (see bar graph).

Yet that same year, some states were taking unprecedented steps to lure nurses to fill open positions in their hospitals, nursing homes and other health care settings. Some examples of recent plans and proposals from the Midwest:

- Kansas created a $50 million initiative for hospitals to offer premium pay (up to $13 an hour) or develop other plans to retain their nurses and support personnel.

- The Des Moines Register reported in December that Iowa would contract with a health care staffing company to bring in out-of-state nurses and respiratory therapists for a temporary period in order to handle a surge in COVID-19-related hospitalizations. The cost was estimated at $9 million.

- In Michigan, an alliance of hospital, nursing home, community college and nurse associations urged legislators to address what it says is “an emerging crisis of a shortage of health care workers.” Its $650 million plan would provide payments to nurses and other health professionals while also establishing a new state-funded scholarship program. Late in the year, too, the Michigan House approved HB 5523, which includes creation of a $300 million Health Care Recruitment, Retention and Training Reserve Fund.

- Bills introduced early this year in Nebraska would provide $50 million in premium-pay bonuses for frontline nurses (LB 1055) and $5 million for a new scholarship program (LB 1091).

The COVID-19 pandemic and a winter surge in cases deepened the demand for nurses, while the availability of new federal funds has allowed states to adopt these pay-boost and retention proposals.

“In the short term, when people are in crisis and nurses are in high demand, then competing on wages is certainly one way to attract nurses,” says Karen Lasater, an assistant professor of nursing and a scholar at the University of Pennsylvania Center for Health Outcomes & Policy Research.

Lasater cautions, though, that it is not a long-term solution to a “chronic issue” that predates the pandemic — not having enough of a state’s existing pool of registered nurses choosing to work in hospitals or other settings due to factors such as stress and burnout.

“It’s a mistake to focus on the pipeline alone without addressing the reasons that the pipeline is leaking,” Lasater says.

Her work has focused on policy levers to improve working conditions, which also is the aim of some recent legislative proposals in the Midwest. Through new bills and programs, too, states are looking to further expand their numbers of people entering the profession. Here is a closer look at ideas in those two areas: building up the pipeline of registered nurses, and repairing the leaks.

Repairing leaks in nursing profession pipeline

One policy lever of particular interest to Lasater is the implementation of state-level, mandatory nurse-to-patient ratios. She says lower caseloads result in fewer patient deaths, shorter hospital stays and fewer readmissions — all due to improvements in care. And for nurses, the chance to deliver better care means less burnout. “[With higher caseloads] there’s a disconnect between what nurses know they should be doing for a patient and what they’re able to because they don’t have enough time,” Lasater adds.

To date, only California has adopted mandatory staffing ratios, and hospital associations have typically opposed these state measures, citing increased costs and less flexibility in other staffing areas. Still, legislation has been introduced in states such as Illinois, Michigan and Ohio.

Michigan’s proposal is part of a three-bill package dubbed the “Safe Patient Care Act,” which also includes new limits on forced overtime and related protections for nurses.

Rep. Sara Cambensy, a sponsor of the overtime bill, says critics of the legislative package point to already-stretched-thin workforce capacity in hospitals during the pandemic. Her response: nurses are leaving, and will continue to do so, without improvements in working conditions.

“We would get more nurses to stay and attract more if we listen to them and address their concerns,” says Cambensy, the daughter of a nurse.

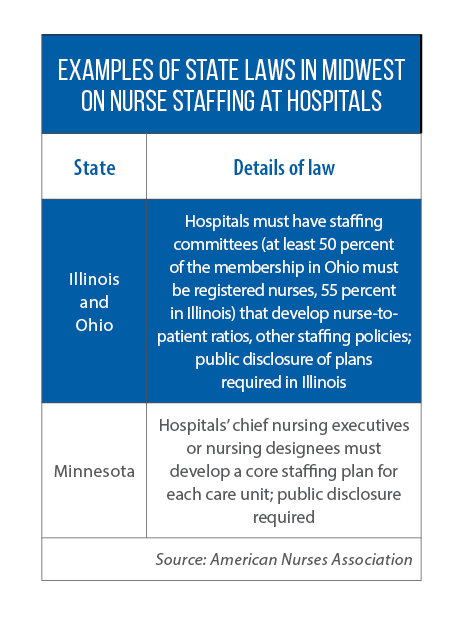

A bill to limit mandatory overtime passed the Ohio House in 2021 with bipartisan support. With exceptions for public health disasters and emergencies, HB 163 would prevent a nurse from working beyond his or her shift as a condition of continued employment. Ohio hospitals also would need to incorporate these new overtime rules into their broader nurse-staffing plans. Already required under state law, these evidence-based plans are developed by a staffing committee, at least 50 percent of whose members must be registered nurses. (In the Midwest, Illinois and Minnesota also have related laws on nurse staffing.)

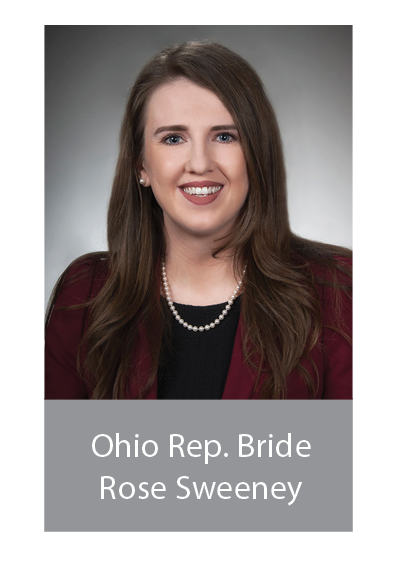

Ohio Rep. Bride Rose Sweeney, a sponsor of HB 163, says similar bills on mandatory overtime have been introduced in multiple legislative sessions, both a reflection of the difficulty in getting such a measure passed (due in part to the opposition of hospitals) and of the fact that concerns about working conditions have been around much longer than COVID-19.

“Like a lot of issues, the pandemic has shone a light on what is a long-standing problem [in health care],” Sweeney says.

In her home state, she adds, some rural areas do lack an adequate supply of registered nurses, but there is no statewide shortage. The more common, persistent problem is keeping enough qualified workers in the profession. “In Ohio, we already have a plethora of high-quality nursing schools in our public and private colleges and universities,” Sweeney says.

Building the nursing profession pipeline

Community colleges across Ohio may soon be added to that list of schools offering bachelor’s degrees in nursing, as the result of language included in last year’s budget bill (HB 110) allowing them to seek such authorization from the Ohio Department of Higher Education. Requests will be granted if the community college can show that nursing is an in-demand field in its region of the state and that it has an industry partner to provide work-based learning and employment opportunities.

Some Michigan lawmakers are pursuing a similar change in state policy. HB 5556 and 5557, passed out of a House committee in late 2021, would allow community colleges to offer bachelor’s degrees in nursing. With this change, Rep. John Roth says, people wanting to pursue nursing as a career would have more choices and flexibility, including the opportunity to seek a degree closer to home.

According to Roth, the community-college option is particularly important in areas of Michigan where traditional four-year options are far away and the shortage of available nurses is acute.

“You hear so much about it now because of the pandemic, but you also heard about it before,” says Roth, whose wife is a registered nurse. “This is not a temporary workforce problem. It’s a long-term thing, and we have a population in our Grand Traverse [County] area that is aging. We’re going to need more nurses.”

Another question for legislators: Does your state have enough people to teach the next generation of nurses?

“You can’t have nursing students, you can’t have nurses, unless you have the faculty, and right now there’s a shortage of faculty in this country,” says Susan Hassmiller, senior adviser for nursing at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and director of its Future of Nursing: Campaign for Action. “So I would say loans, I would say scholarships and lower payments for nursing faculty [as policy options].”

Illinois lawmakers considered an income tax credit for nurse educators last year, but the final language of SB 2153 did not include such a provision. However, the enacted bill does authorize the Department of Public Health to award up to $500,000 a year in scholarships for individuals seeking initial or advanced degrees in nursing.

Under SB 2153, too, Illinois added new requirements to its existing law on hospitals’ nurse staffing committees. For example, the committee must meet at least six times a year, and at least 55 percent of its members must be direct-care nurses (up from 50 percent under the previous law). And if a hospital rejects a committee’s plan for nursing-to-patient ratios, it must provide a written explanation. Non-compliant hospitals face fines, and that money will go to the scholarship fund. (Dollars also come from hospital licensing fees.)

Across the Midwest, often as part of larger initiatives that target high-demand career sectors, many states already offer scholarships and other financial assistance to help build the nursing pipeline. Examples include a workforce development scholarship in Minnesota and grants in Indiana (known as Next Level Jobs) for individuals to pursue nursing-related degrees or certificates.

Early this year, Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds announced plans for high school apprenticeships that introduce students to the nursing profession and allow them to graduate as certified nursing assistants.

Hassmiller also suggests that states look for ways to diversify their nursing workforce. One recent example from the Midwest: a new dual-admissions pathway for nursing students between the City Colleges of Chicago and University of Illinois-Chicago. A central goal of this new partnership is to improve access to the profession among historically underrepresented racial and ethnic groups.

Other state options include changing rules on licensing

Along with having a central role in training the next generation of nurses, states also control licensing and regulation. Both Hassmiller and Lasater suggest that policymakers look at some of their states’ existing rules and statutes.

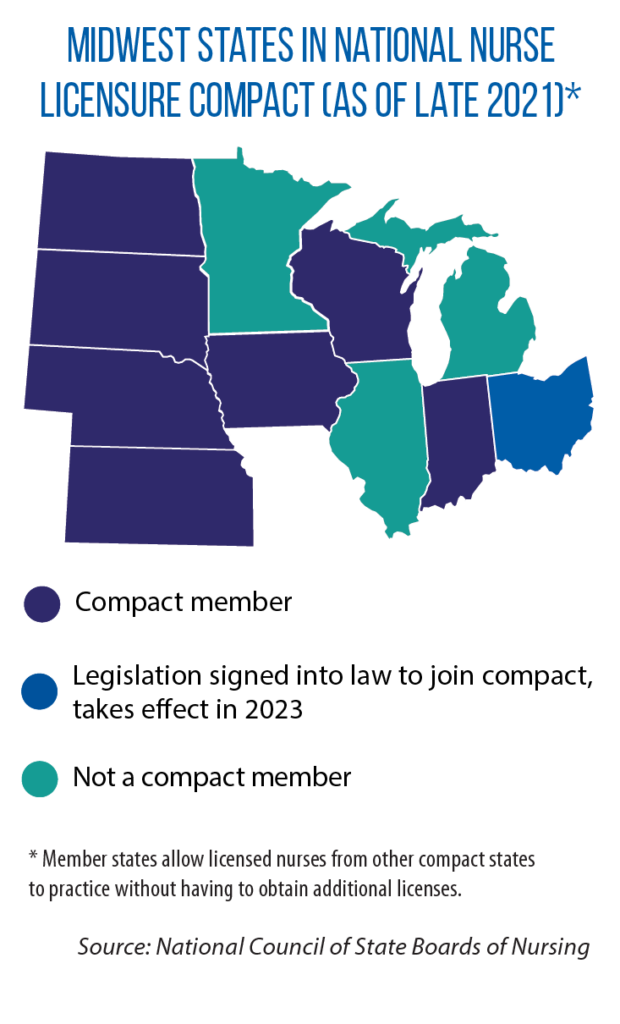

For example, is your state part of the national Nurse Licensure Compact? Under this agreement, member states allow licensed nurses from other compact states to practice without having to obtain additional licenses. The removal of this kind of regulatory burden has the potential of adding to the pool of available nurses in geographic areas of the state with shortages, Lasater says.

Ohio is set to become the eighth Midwestern state in the compact, as a result of the passage in 2021 of SB 3. (Only Illinois, Michigan and Minnesota are not members.)

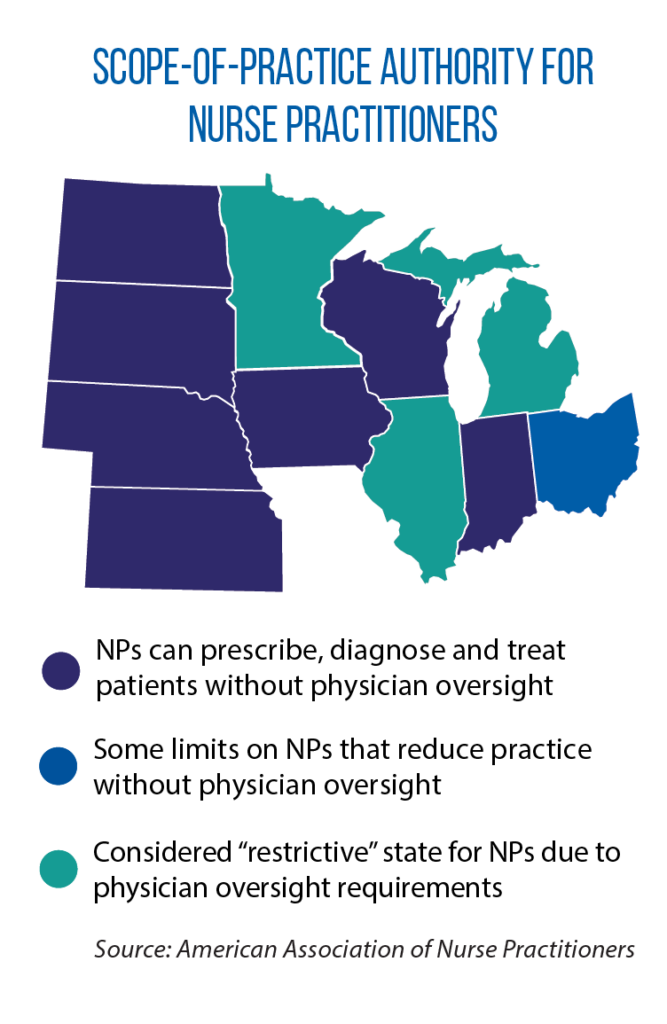

For nurses who pursue and obtain advanced degrees, opportunities can vary from state to state because of rules on “scope of practice.” Currently in the Midwest, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota and Wisconsin give nurse practitioners the authority to prescribe, diagnose and treat patients. Their scope of practice is more limited in other states. With greater authority, Hassmiller says, nurse practitioners can reduce health costs everywhere and deliver quality care in areas with shortages of doctors and other providers.